IS 'caliphate' crumbles as Iraq tightens noose on Mosul

- Published

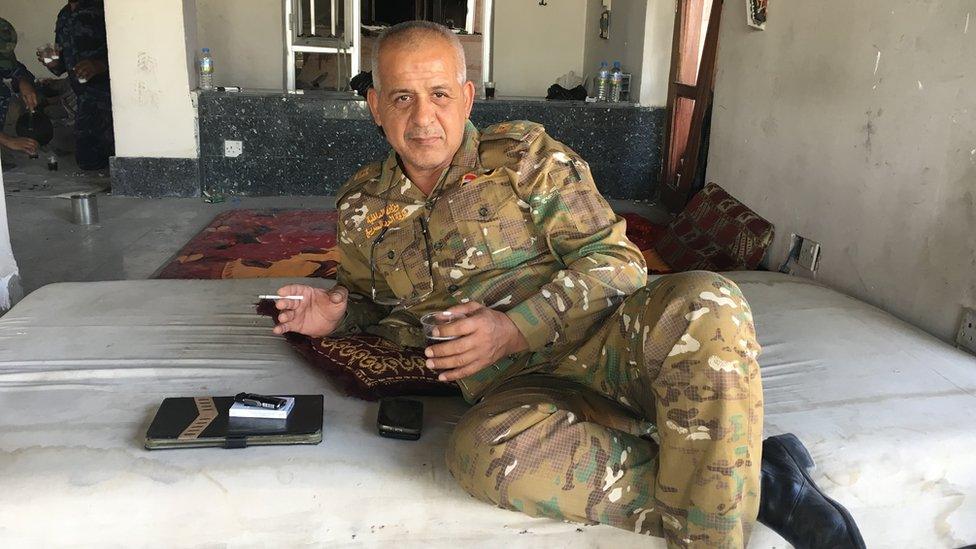

Orla Guerin on the front line in Mosul

It was three years ago that a lightning advance by about 800 jihadist fighters in northern Iraq morphed into a global threat.

Having taken over Mosul, Iraq's second largest city, the extremists proclaimed the birth of their so-called "Islamic State".

As their self-styled caliphate marks its third anniversary, Iraqi forces are getting ready to pronounce its death - at least on their soil.

In Mosul, which was the largest city under IS control, the remaining militants are corralled in the narrow alleyways of the Old City.

Elite counter-terrorism units are hunting them down, house-to-house and room-to-room, in an area of about one square mile (2.6 sq km).

Troops escorted us through the battle zone, where little stands except mounds of rubble.

Here and there we spotted matted piles of human hair. Locals say militants left their beards behind as they fled.

In the streets where they dispensed terror, the corpses of "Islamic State" (IS) fighters now lie rotting in the sun.

More than 800,000 civilians have been displaced by the battle for Mosul

We saw some of their victims fleeing on foot, taking only their children and their trauma.

"We couldn't move, we couldn't do anything," said Ilham, a gaunt woman in a black headscarf, who was escaping the fighting with her family. "They were completely in control of everything. We were afraid to go anywhere."

As she spoke a neighbour, Sebham Jassem, doused his young sons in bottled water handed out by Iraqi troops.

"We had no clean water for two months," he said. "Five mortars landed on our house and it was destroyed. We were hungry and scared. Our lives were a disaster."

The Iraqi army says it has recaptured about half of Mosul's Old City

The campaign to free this ancient city has dragged on for almost nine months.

I watched the opening shots being fired last October by Peshmerga fighters, from Iraq's autonomous Kurdish region, who swept towards Mosul.

They were part of a complex coalition against IS that included the Iraqi security forces, state-sanctioned Shia militias, and Sunni tribal fighters.

After the liberation of Mosul - a predominantly Sunni city - the scramble for power here could involve Turkey and Iran, and threaten the future of Iraq.

There is already one flashpoint on the horizon - the Kurds have announced plans for a referendum on independence in September.

Even as Iraqi leaders prepare to declare victory in Mosul, there is a sense this battle may have to be fought again.

Like al-Qaeda before it, IS found support among marginalised Sunnis in Iraq.

The minority community complains of discrimination by the Shia-led government in Baghdad. Unless that changes the extremists could be back.

Iraq's military has not disclosed casualty figures but commanders admit to heavy losses

As he toured newly liberated streets in the Old City, a commander of Iraq's Counter Terrorism Service conceded that IS could be reborn.

"We can't tell now," said Maj Gen Maan al-Saadi. "It depends on the politicians. It's complicated in Iraq. What I can tell you is that this country is now cleaned of IS. "

The militants who once controlled a third of Iraq may now be reduced to a few pockets of resistance, but Mosul bears many new scars.

Mohammed Abdul Karim had an IS headquarters right beside his house, and a makeshift IS prison behind it. From his living room, the 30-year-old could hear the screams of those inside.

A few months ago he joined them. IS detained him at work angry that he was repairing mobile phones, which they had banned.

He walked me through the gates of the large two-storey house where he was held, pointed out the handcuffs still attached to the downstairs window.

"They brought a prisoner over here, and tied him up," he said rushing to a tree in the driveway.

"They put water all over his body. Then they brought two electric cables and shocked him until he fainted. They woke him and did it again. Later they rolled him up in a blanket."

The Great Mosque of al-Nuri and the leaning al-Hadba minaret were destroyed by IS last week

Mr Abdul Karim said the man was one of two he saw tortured to death in this way.

Another young man was beaten all over his body because he was suspected of providing intelligence to the Iraqi army.

"They beat him so much he confessed just to end the pain," he said. "After that they killed him."

After Mosul is fully liberated more accounts like this may emerge, and new tensions may come to light - between those who opposed the extremists and those who backed them.

Mr Abdul Karim said some of his neighbours joined the militants. If they returned to their homes, he added, he would do to them what IS did to his fellow prisoners.

Security forces are advancing into a hospital complex where IS militants are holed up

When this city finally regains its freedom the celebrations may not last long - for Mosul, or for Iraq.

Many military families across the nation will be mourning sons killed in the fight here.

Iraq has not disclosed casualty figures but commanders admit to heavy losses.

"We lost many martyrs here, all of them young," said Lt Col Mohammed Diab al-Tamimi of Iraq's Emergency Response Division.

Lt Col Tamimi says he is always preparing for "another battle"

"I miss them. Their families miss them and the country misses them. But they did not die for nothing. They died for this country. May God take them to paradise."

Col Tamimi and his men have been fighting for days to clear a hospital complex where about 200 IS militants are believed to be holed up in a basement.

Asked if he thought the militants might re-emerge in future his response was swift.

"In Iraq," he said, "there is always another battle."