Syria war: Meeting Syria's generals in the desert

- Published

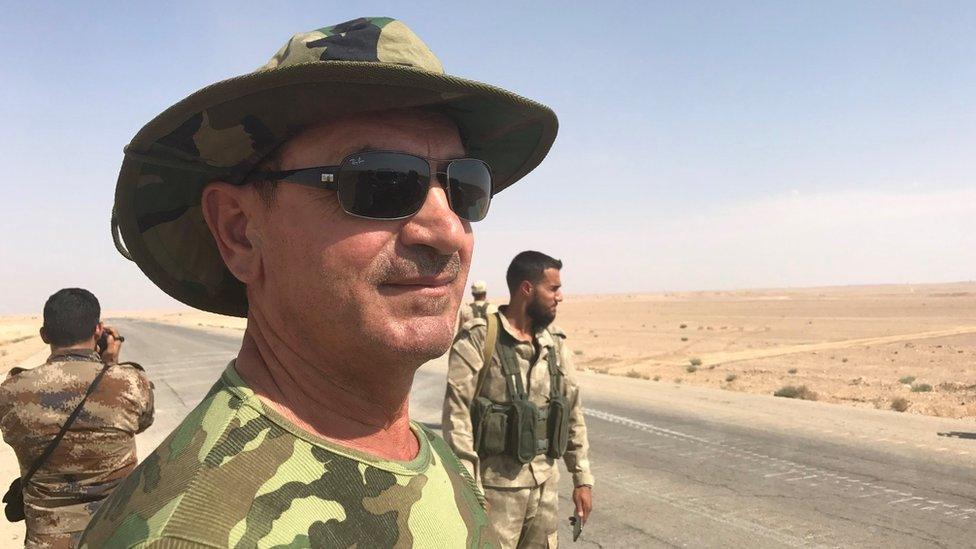

Gen Mohamed Khaddour has fought on almost every front in Syria

The jagged ruins of Sukhna, rising in the midst of an infinite expanse of desert sand, can feel like the middle of nowhere.

But this strategic crossroads in eastern Syria, surrounded by gas fields, is a major prize for Syria's army in its offensive against the last remains of so-called Islamic State's crumbling self-declared caliphate in Syria.

"It's a significant victory," declares Gen Mohamed, his eyes shaded from the glaring heat by mirrored aviator sunglasses.

The squat muscular soldier who offers only his first name had suddenly - and surprisingly - leapt from his gleaming white vehicle and strutted across the ribbon of tarmac when he spotted our team inspecting a road sign defaced by IS' infamous black signature at the entrance to this ravaged desert town.

"Sukhna was Daesh's [IS'] most important hub in this area and we've now opened the road to Deir al-Zour," he explains in reference to the next populated centre in their sights. The neighbouring governorate of Deir al-Zour is almost completely controlled by IS, except for a besieged section of its main city and a Syrian airbase still in use.

We are the first journalists to be taken to this abandoned town just captured by an advancing Syrian army. Its steady stride across the vast sweep of the baking hot eastern desert is accelerating with the powerful punch of Russia's warplanes and special forces, an array of Iran-backed militias and local tribes.

Abandoned tea cups

Every building on every street in Sukhna bears the scars of another brutal Syrian battle. Not one escaped intact.

Residents of Sukhna fled IS three years ago

Fronts ripped away reveal, like dusty dolls' houses, tables and chairs and even tea cups abandoned in haste when IS fighters stormed this desert town three years ago. Almost everyone fled.

Defeated IS fighters are now beating a retreat towards Deir al-Zour's capital, which bears the same name, about 130km (81 miles) away, across this desolate tract.

More than 200 fighters were killed this week when Russian warplanes blitzed a column of vehicles and weaponry snaking its way toward one of IS' last redoubts on Syria's ever so tangled battlefield.

To the north of Sukhna lies Raqqa, once IS' self-styled Syrian capital. It is now under blistering attack by the mainly Kurdish Syrian Democratic Forces, buttressed by US special forces on the ground and US-led coalition warplanes in the skies of north-western Syria.

There is mounting alarm among aid groups and activists about the rising civilian death toll from aircraft and artillery strikes as the battle intensifies and IS fighters trap residents inside as they make their last stand.

What will also be a punishing battle to retake the city of Deir al-Zour, where IS fighters are also digging in, may only be weeks away.

Sanctions list

"We're hell-bent on victory," vows the the second Syrian general we meet in Sukhna. Commanding officer on this eastern front Gen Mohamed Khaddour takes the wheel himself to drive us to their new forward firing position about 10km (six miles) outside the town.

As if to prove his mettle, he brandishes his arm bearing his wounds of war. "Look at my arm," he declares. "I've been injured three times."

Sukhna was quickly abandoned by most of its residents when IS arrived

With his floppy desert hat and casual fatigues, he is every inch the battle-hardened commander, revered by his own, reviled by his enemies. He has crushed rebel forces, with brutal efficiency, on almost every major front across Syria since the uprising erupted more than six years ago.

The general brings up that he is on the EU's sanctions list, external. He is number 125, accused of "being responsible for repression of peaceful protests" in 2011 in the Damascus district of Douma which saw some of the first and biggest demonstrations in the capital.

He brushes away the charge in this rare meeting with Western journalists, saying his focus is on this new front. "I'm fighting Daesh," he asserts.

Russian muscle

Sukhna is in ruins

An artillery barrage kicks up a cloud of fine sand which momentarily obscures any view. As it clears, a plume of brown smoke rises on the horizon. The closest IS positions are only a kilometre away, just beyond the ridge.

As the Gen Khaddour huddles with his men to assess the strikes, Russian special forces join the discussion, their faces obscured by woollen masks in the presence of journalists. The Russians put a stop to any filming while they are in sight.

I ask the general if it complicates matters that Americans are also fighting on Syrian territory.

"They have a completely different direction," he replies, adding, "We're only focusing on Deir al-Zour."

But in case there is any doubt, he declares, "There's no power on the ground which can stop us from taking back what we want to take back."

The next front?

In this war against IS, all guns are now pointing in the same direction, against a common threat on what must be the world's messiest political battlefield.

But there is a much bigger game here for President Bashar al-Assad's men. Recent battlefield successes on key fronts against Syrian rebel groups have freed up some of their forces, and those of their friends, to enable this determined push across eastern Syria.

Local ceasefires, backed by Moscow's political and military muscle, have brought relative quiet to some remaining rebel enclaves. But every officer we spoke to was adamant that the north-west province of Idlib, the biggest opposition stronghold, would be their next target after the IS caliphate collapses.

The territorial defeat of IS may now be only a matter of months. When that day comes, Syria's other war, with its changing political kaleidoscope of outside powers and interests, will shift into a new stage in the next new front in the punishing battle for Syria.