How historical Afrin became a prize worth a war

- Published

Afrin has been semi-autonomous since Syrian troops pulled out in 2012

Afrin and its environs are beautiful, a rich prize worth fighting for. The region is known as Kurd-Dagh - the Mountain of the Kurds - where 360 thriving Kurdish villages make it the most densely Kurdish populated part of Syria.

The Afrin River runs north-south through heavily treed hills. The lush valleys and fertile red soil are renowned for their excellent fruit and nut produce, especially olives.

No snakes or scorpions are said to inhabit this soil. Water flows in abundance.

Afrin is famed for its olive groves

The Midanki Falls were tamed in 2004 by a dam so the old road now vanishes abracadabra-like into a long thin lake.

At weekends locals picnic and barbecue round its shores. Arabic is hardly spoken north of Midanki and older men still dress traditionally in baggy black trousers.

Neighbouring Azaz is also home to many Turkmen and Arab communities. Almost everyone, Kurds included, is Sunni Muslim. Kurdish identity is based not on religion, but on ethnicity and cultural heritage.

Overlooking the Afrin River, within sight of the Turkish border, sprawl the vast Roman ruins of Cyrrhus, a suitable vantage point from which to digest the epic struggles of this region and to ponder the dilemmas unfolding here today.

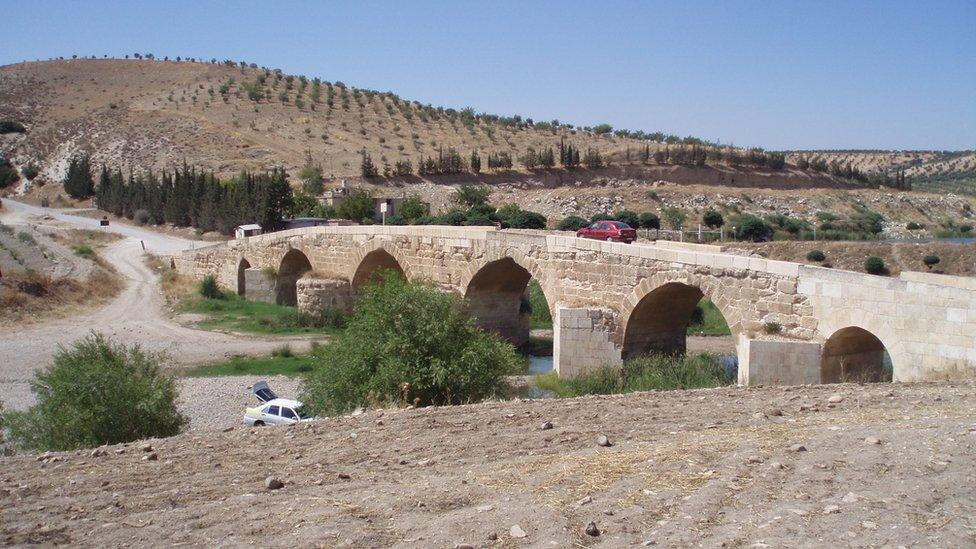

A Roman bridge across the Afrin River is still used by traffic

Cyrrhus once served as a military base for the Romans conducting campaigns against the Armenian Empire to the north. By the 4th Century it had become an important centre for Christianity with its own bishop, but was abandoned in the 12th Century after losing its strategic role.

Nearby stands the landmark which gives the site its local name, al-Nabi Houri, the pyramid-roofed tomb of Uriah the Hittite, sent to his death in battle by Israelite King David so that he could marry the lovely Bathsheba, his widow, according to the scriptures.

Tomb of Uriah the Hittite, killed on the order of King David, according to the scriptures

Today the tomb is a Muslim shrine and mosque, tended by a Kurdish household whose patriarch lost his leg, not in battle, but in a minefield as he crossed the Turkish border to visit relatives.

Border disputes

Such complexities are reflected in a 1935 map of Syria compiled by troops of the French Mandate.

It shows the religious and ethnic communities of Syria just before the French gifted the Sanjak of Alexandretta on the Mediterranean coast to Turkey as a bribe to keep it neutral in World War Two.

A 1935 French Mandate map of Syria and Lebanon

The Turks renamed it Hatay, its population then estimated at 50% Arab, 40% Turkish and 10% Armenian.

Syrian maps still mark the Hatay border as "temporary".

Throughout the volatile seven-year Syrian war, conflicting parties routinely produce maps with differing claims of territorial control.

Afrin, abutting Hatay to the west and rebel-held Idlib to the south, is the latest victim, as Turkey once again tries to force what it sees as "terrorist Kurds" out.

The last time was in 1998, when Syria was sheltering Turkey's nemesis Abdullah Ocalan and his Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK), which has waged a decades-long insurgency for autonomy in south-east Turkey.

As a result of Turkish pressure, Syria expelled the group and its leader.

Competing interests

When Syrian President Bashar al-Assad's soldiers quietly withdrew from northern Kurdish areas in summer 2012, the well-organised Kurds of the Democratic Union Party (PYD) - the dominant Kurdish party in northern Syria, regarded by Turkey as an extension of the PKK - quickly took charge, setting up their own education system and administration.

The PYD's armed wing, the People's Protection Units (YPG), effectively became the military.

Kurdish soldiers are tough, used historically by the Ottomans and the French, and today by the Americans to help fight the Islamic State group (IS) in Syria.

Why is Turkey attacking Syria? Mark Lowen explains

But the real fight may yet be among the Syrian Kurds themselves, for not all support Mr Ocalan, despite the omnipresence of his photo.

Thousands have fled PYD rule in order to escape large-scale conscription and the use of child soldiers. Many complain the PYD are mercenaries and criminals.

Stories of human rights abuses abound, like bulldozing Arab villagers' homes on the pretext of clearing out IS extremists, accusations the PYD denies.

Since 2015, private schools, including those teaching in Arabic, have been forced to close by the Kurdish administration.

Meanwhile, the Syrian state continues to issue all civil documents, such as birth, marriage and death certificates, in an attempt to maintain influence.

With so many competing interests, the fight for Afrin will be ugly. Kurdish dreams of "democratic federalism" and Turkish dreams of safe zones free of "terrorists" may lead inexorably to Syria's de facto partition.

Whatever the future holds for Afrin, one side's dream is likely to be the other's nightmare.

Diana Darke is the author of several books on Middle East society, including My House in Damascus: An Inside View of the Syrian Crisis (2016), and The Merchant of Syria (2018). Follow her on Twitter, external.

- Published22 January 2018

- Published20 January 2018

- Published28 March 2018

- Published15 October 2019

- Published2 May 2023