Palestinians fear cost of Trump's refugee agency cut

- Published

Unrwa provides critical services, including education and health care

"Dignity is priceless," read the signs as thousands of employees of the UN agency for Palestinian refugees march through central Gaza City.

They fear Washington's recent decision to withhold $65m (52.5m euros; £46m) - possibly rising to $290m - in funds could affect their positions as well as basic services which most of them, as refugees, rely on.

"Unrwa was there every moment for me," says Najwa Sheikh Ahmed, an information officer with the UN Relief and Works Agency.

"It gave not only food, clothes, education and healthcare but also a job and the opportunity that offers your family."

Najwa was born in Khan Younis refugee camp and brought up in tough conditions.

Thousands of Unrwa supporters and staff have held protests in Gaza

She moved to Nuseirat camp when she married her husband, who is also Unrwa staff. They have five children.

When I visit, we pass along narrow streets to the local clinic, painted in the blue and white colours of the UN, so Najwa can get a medical check.

I watch her eldest daughter, Salma, as she excels in an English lesson. She is one of 270,000 Unrwa students in Gaza.

Salma Sheikh Ahmed attends lessons in an Unrwa-run school

"As a mother I feel very worried," Najwa confides.

"If the funding gap isn't bridged, then Unrwa might find itself in a situation where [it has] to close the schools and health services. My children will be at risk."

Ties cut

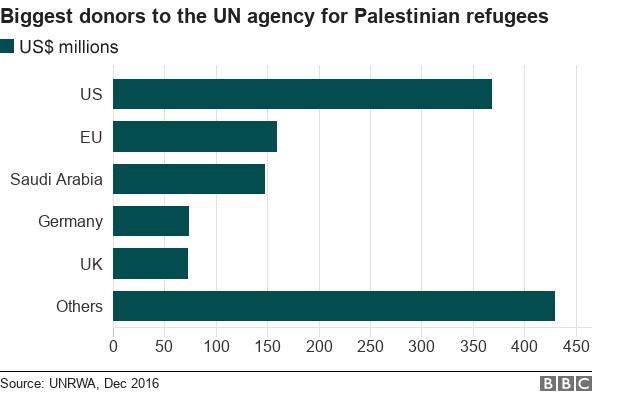

The US is the largest single donor to Unrwa. Last year, it gave the agency around $360m - about half of the total amount it gave in support to the Palestinians.

President Donald Trump first indicated a change in approach on 2 January when he Tweeted that his country got "no appreciation or respect", external for the large sums of aid it gave.

The State Department insists that freezing Unrwa funds is linked to needed "reforms", but suspicions remain that it is meant to punish Palestinian leaders.

They cut ties with the White House weeks earlier after it recognised Jerusalem as Israel's capital. The Palestinians claim East Jerusalem as the capital of their future state.

Last week in Davos, Switzerland, Mr Trump said that aid to the Palestinians would be suspended "unless they sit down and negotiate peace".

Special status

In the impoverished Gaza Strip, which has eight refugee camps, ordinary people complain that they find themselves helplessly caught up in geopolitics.

Unrwa was originally set up to take care of hundreds of thousands of Palestinians displaced by the 1948 Arab-Israeli war.

Nearly 70 years on, some of those refugees and many of their descendants continue to live in camps, which are now chronically overcrowded breeze block neighbourhoods.

More than five million Palestinians are registered as refugees

Unrwa supports some five million people not only in the Palestinian Territories but also in Jordan, Lebanon and Syria - where Palestinian refugees have limited rights.

The fate of the refugees is a core issue in the Arab-Israeli conflict and they have often been at the heart of Palestinian political and militant activity.

Palestinians call for their "right to return" to parts of historic Palestine - land which is now in Israel.

Israel rejects that claim and has often criticised the set-up of Unrwa for the way it allows refugee status to be inherited, which it points out is uniquely applied to Palestinians among all the world's refugees.

"How long are we going to have Unrwa? Another 70 years?" the Prime Minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, said to me at a recent press event.

"We already have great-great-grandchildren who are refugees - who are not refugees but they're on the list of Unwra."

The US says Unrwa needs to become more accountable

Mr Netanyahu suggests donations should be shifted to other humanitarian agencies, including the UN High Commission for Refugees.

"It will have positive effects because the perpetuation of the dream of bringing the descendants back to Jaffa is what sustains this conflict," he told me.

"Unrwa is part of the problem not part of the solution."

Alternatives 'worse'

Unrwa officials stress that the UN General Assembly sets their mandate and dismiss the idea it obstructs any Israel-Palestinian peace deal.

"It is the failure of the political parties to resolve the refugee issue that perpetuates it," says Unrwa spokesman Chris Gunness.

"As soon as there's a resolution of that based on international law, based on United Nations resolutions, Unrwa will go out of business and hand over its service."

Israeli defence officials warn Unrwa's collapse could trigger an escalation in violence

The agency has now launched a global appeal to fill the gap in its budget and is receiving many messages of support, external - including from celebrities and 21 international humanitarian groups.

Some in Israel also raise concerns that weakening Unrwa could cause regional instability and create more extremism.

"While Unrwa is far from perfect, the Israeli defence establishment and the Israeli government as a whole, have over the years come to the understanding that all the alternatives are worse for Israel," a former Israel Defense Forces (IDF) spokesman, Peter Lerner, wrote in Haaretz newspaper, external.

At the rally in Gaza City, participants focus on the impact of any Unrwa cutbacks on the most needy but also on existential issues.

"Without Unrwa nobody will identify us as refugees," says Najwa Sheikh-Ahmed - whose father fled from his home in al-Majdal - now in Ashkelon in southern Israel - as a boy in 1948.

"My refugee number, my ration card is witness to the fact that once upon a time I had a homeland," she says. "Without this we will lose the right to fight for our rights."

- Published17 January 2018

- Published16 January 2018

- Published3 January 2018

- Published3 January 2018

- Published26 June 2023