Syria war: Families struggle to survive in Eastern Ghouta, under siege

- Published

The UN has accused the Syrian government of a "monstrous campaign of annihilation"

A four-day-long bombardment by Syrian government forces is reported to have killed more than 300 civilians in the rebel-held Eastern Ghouta area. Here, people living there tell their stories.

The enclave - home to an estimated 393,000 people - has been under siege since 2013. But pro-government media say a major military operation might soon begin to clear rebel factions from their last major stronghold near the capital Damascus.

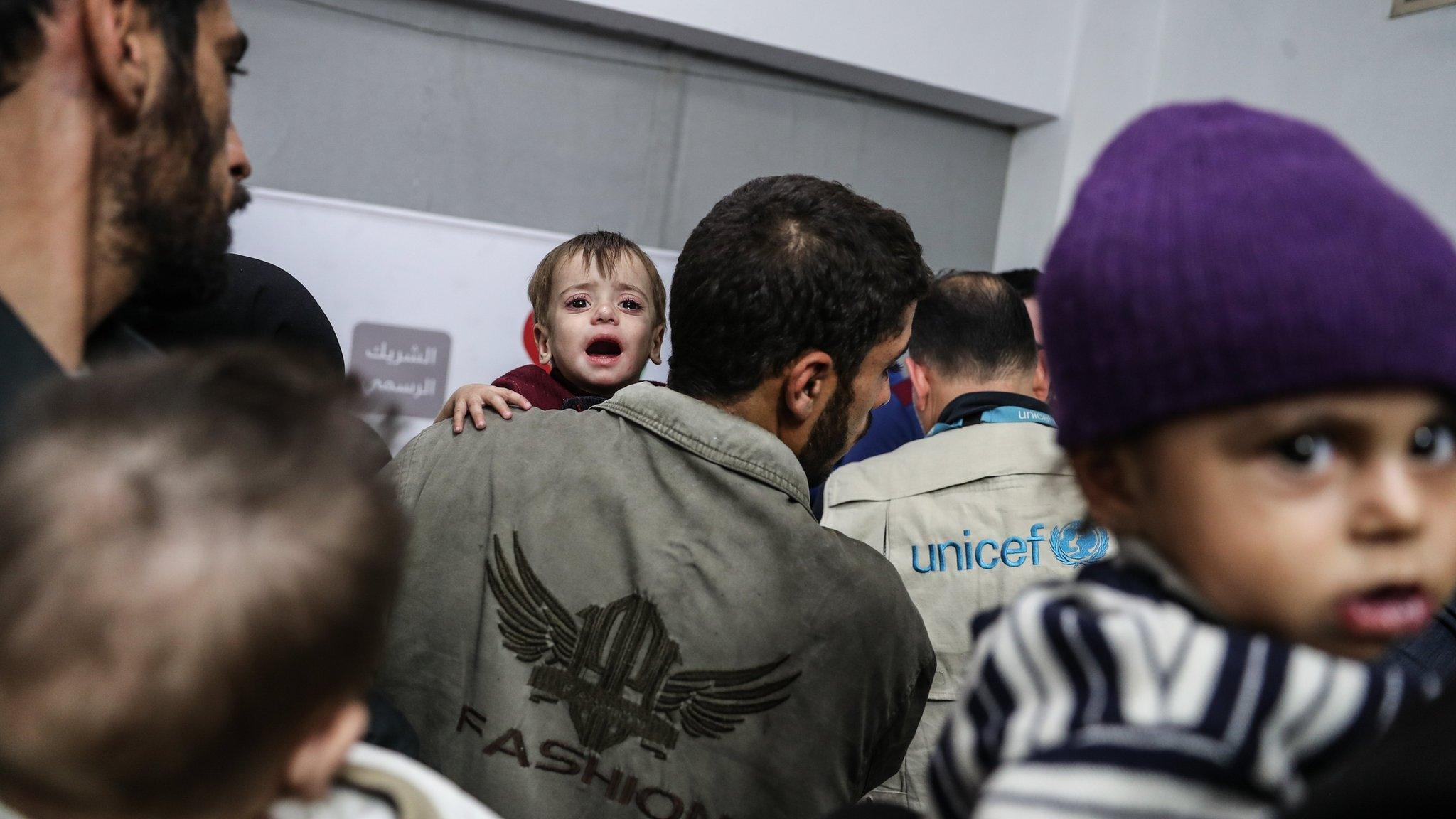

The relentless air and artillery strikes are leaving civilians, particularly women and children, in a state of fear and forcing them to seek shelter underground, where they are largely deprived of food and sanitation.

'So afraid her hair is falling out'

"We are living in a basement, underneath a half-destroyed house," Asia, a 28-year-old student and mother-of-three whose husband was killed in an attack while he was on his way to work, told the BBC.

"My daughter is sick. Her hair is falling out because she is so afraid."

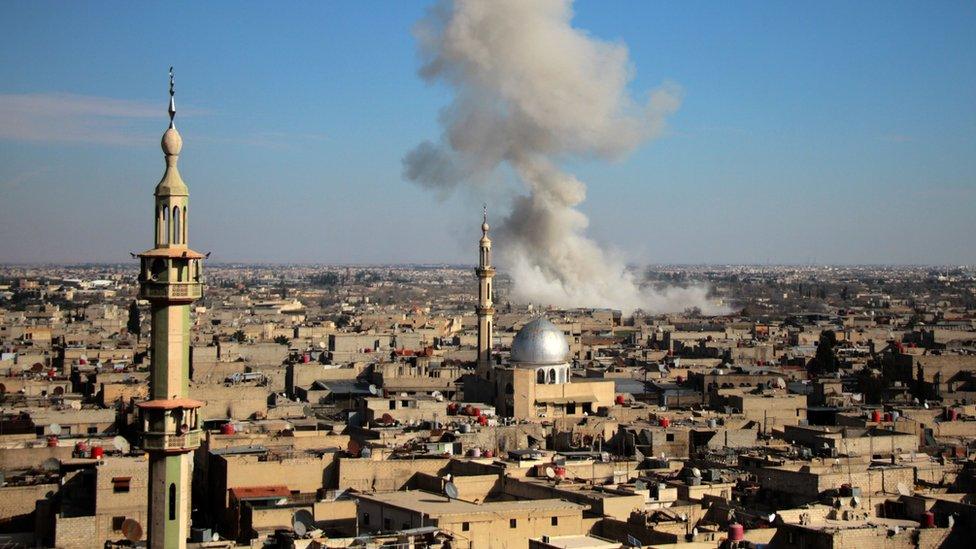

Activists say residential areas across the Eastern Ghouta have been deliberately targeted

The Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, a UK-based monitoring group, says the government and its allies have carried out more than 1,290 air strikes on the Eastern Ghouta and fired 6,190 rockets and shells at the region since mid-November, when hostilities between government and rebel forces escalated.

Between Sunday and Wednesday alone there were reportedly about 420 air strikes, and 140 barrel bombs were dropped by helicopters.

UN war crimes experts are also investigating several reports of rockets allegedly containing chlorine being fired at the Eastern Ghouta this year.

The recent surge in casualties means that more than 1,070 civilians, including several hundred children and women, have been killed and 3,900 injured in the past three months, according to the Syrian Observatory.

Mouayad, a 29-year-old graduate with two young children, told the BBC: "You cannot imagine how hard it is.

"For these kids to live their childhood in safety you have to keep them in the basement. They cannot get out, play in the garden, or anything else."

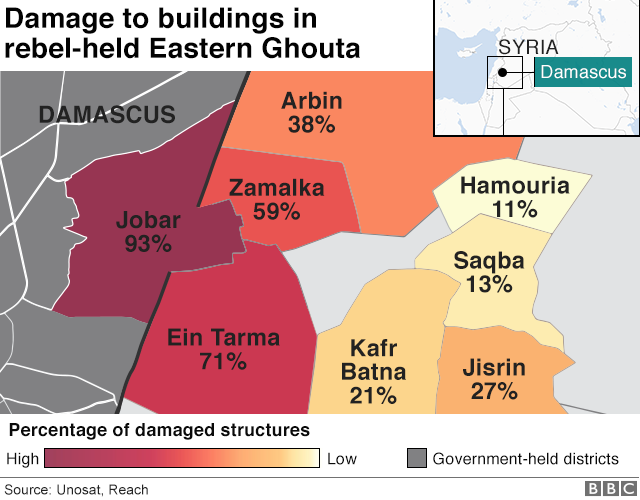

Satellite imagery analysis by UN experts in December identified approximately 3,853 destroyed, 5,141 severely damaged and 3,547 moderately damaged buildings, external in the more densely-populated western parts of the enclave.

In the suburb of Ain Tarma, where between 17,000 and 20,000 civilians are believed to live, 71% of structures are damaged or destroyed, according to the analysis. In the neighbouring Jobar, where only rebels remain, the figure is 91%.

The Syrian government says it is targeting "terrorists" and not civilians

The Ghouta is the name given to the agricultural belt that runs around the east, south and west of Damascus. It includes suburbs of the capital, as well as a number of outlying towns and villages.

People living in the Ghouta were among those who took part in the peaceful pro-democracy uprising against President Bashar al-Assad in 2011. When the uprising evolved into a civil war, the region became a rebel stronghold.

In 2012, government forces began to besiege parts of the Ghouta. The following year, they were accused by Western powers of firing rockets filled with the nerve agent Sarin at several rebel-held areas in the region, killing hundreds of people. Mr Assad denied the charge, blaming rebel fighters.

As the president and his allies, Russia and Iran, gained an upper hand in the war over the last three years, they became determined to regain control of the Ghouta. The sieges were tightened, deliveries of humanitarian aid were limited, and the bombardment was stepped up.

The UN expressed outrage at the so-called "starve-and-surrender" tactics, but the government continued. In late 2016, residents of the last rebel-held towns in the Western Ghouta surrendered. However, the Eastern Ghouta held out.

Low food supplies and high prices

Many people there were able to obtain essential foodstuffs via an informal tunnel network connecting the Eastern Ghouta with neighbouring government-controlled districts of Damascus, as well as from traders who had arrangements with troops.

But last year, the government closed many tunnels and limited trade. From September until the end of November, no commercial vehicles were permitted to enter the Eastern Ghouta at all, external, according to the Reach Initiative, which is in touch with people on the ground to gather humanitarian information.

People reportedly go days without eating, consume non-edible plants, or reduce meal sizes

Limited deliveries resumed in December, but the restrictions led to the exhaustion of food supplies and extremely inflated prices.

Humanitarian organisations were prevented by the government from delivering aid in December and January, although one convoy carrying assistance for 7,200 people reached Nashabiya in mid-February.

"There are some dealers. They provide the Ghouta with flour, rice, sugar," said Mouayad. "But even the dealers... are stopped right now from entering or exiting."

Today, a bundle of bread costs close to 22 times the national average, external, according to the UN. Malnutrition rates have reached unprecedented levels, with 11.9% of children under five years old acutely malnourished.

The government has allowed one aid convoy into the Eastern Ghouta since late November

Residents told Reach that they went days without eating, consumed non-edible plants, or reduced the size of their meals due to a lack of access to food.

'Unfortunately I do not have enough'

"For my three-year-old son, I make bread. For my daughter, I search for a cow to bring milk," Mouayad said. "I am an educated person. I can get money for my children. Other people, other families, cannot do that."

Even then, Mouayad explained that he had only enough money to pay for food for his own family for a few days more. He did not know what he would do after that.

Asia does not have a job and cannot afford to buy much food when she is able to venture outside. Her father and brother are both dead.

"I receive money for my children from an organisation helping orphans, but unfortunately I do not have enough," she said.

Young children have been found buried in the rubble

Access to healthcare has also been severely limited by the siege and bombardment.

Last month, a total of 29 primary healthcare facilities, hospitals, informal emergency care points and mobile clinics were still operating, Reach said.

Ambulances 'intentionally targeted'

But since Sunday night, 14 medical facilities have been taken out of service as a result of government attacks, according to Dr Ahmad Dbis of the Union of Medical Care and Relief Organizations (UOSSM), which operates hospitals there.

More than 10 medical staff and volunteers have also been killed and 20 injured.

Dr Dbis said medics were being forced to sleep at the hospitals because it was too dangerous to leave. Ambulances were also unable to transport patients because they were being intentionally targeted by aircraft, he added.

Doctors are having to treat wounded people with limited medical supplies and equipment

He recalled how he had been in contact with his friend, UOSSM photographer Abdoulrahman Ismael, external, on Tuesday shortly before he was killed in an air strike.

"I heard the sound of bombs. I asked him 'what was that?' And he said there were barrel bombs 200m away. I asked him whether he was in a safe place.

"He said 'Yes, I am in a medical centre in Hamouria. I think it is safe.' Four minutes later, his internet connection went dead."

'Between fire and knife'

Dr Dbis said the situation was so bad in the Eastern Ghouta that doctors were only treating emergency cases. They also have to cope without key supplies, including anaesthetics, antibiotics, blood transfusion bags and clean bandages.

Hundreds of critically sick and wounded patients are also in need of urgent medical evacuation for life-saving treatment. Twenty-nine were evacuated at the end of December, but the UN said another 22 died while awaiting permission to leave.

A hospital in the town of Hamouria was bombed on Tuesday

The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Zeid Raad Al Hussein, has urged the international community to take concerted action to stop what he called a "monstrous campaign of annihilation".

The government and its allies have denied attacking civilians and rejected calls for a ceasefire or humanitarian pause. They say they are trying to liberate the Eastern Ghouta from "terrorists" and stop mortar and rocket attacks on neighbouring government-controlled areas, which have reportedly killed 113 civilians since mid-November.

That has left many fearing that there will be a bloody battle like that seen in East Aleppo in late 2016, when rebels and civilians were bombed into submission.

"I hope that we can leave the Eastern Ghouta because we cannot bear any more of this," said Asia.

Mouayad said he tried to escape the siege five years ago but failed.

"Unfortunately, my situation is now between fire and knife. Fire from bombing and shelling here in Eastern Ghouta. And the knife - terrorism in Syria from al-Qaeda or IS. There is no safe exit."

"I want peace for my country. I want to raise my children in a respectful way. I want them to live in peace in any possible way. I want safety for my children," he added.

- Published20 February 2018

- Published14 February 2018

- Published7 February 2018

- Published18 December 2017

- Published27 December 2017

- Published2 May 2023

- Published20 February 2018

- Published20 February 2018