Crossing Divides: Lebanon civil war veterans fight for peace

- Published

Fighters wage peace after Lebanon's civil war

From a cliff top, high in Mount Lebanon, two smartly dressed men survey the landscape and recall the days they tried to kill each other.

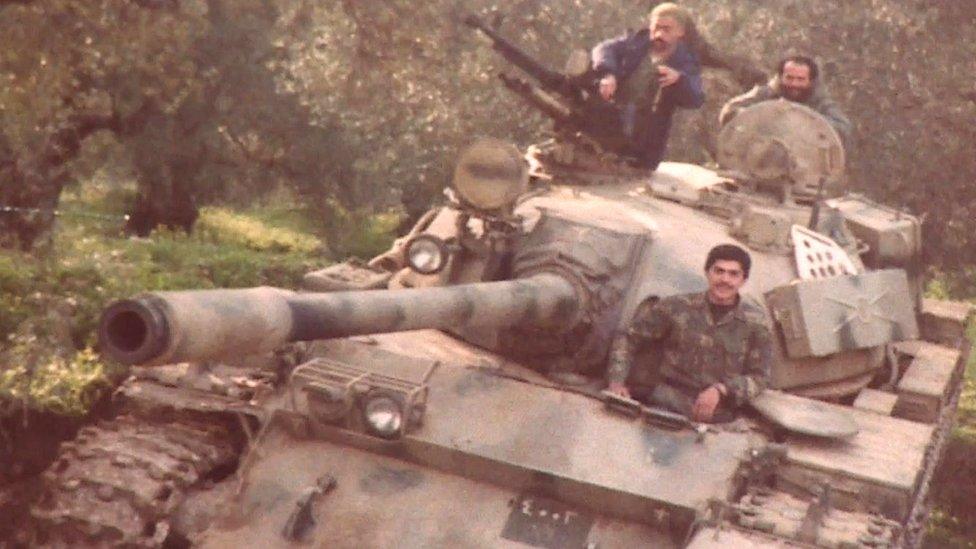

"I was positioned on that hill," Badri Abou Diab remembers, looking across what was once no man's land in a bitter civil war. "We used to rejoice when our tanks hit a target anywhere on the other side."

Antoun Moukarzel raises binoculars and points to the towering hill near the town of Jahliyeh, where he was positioned some 35 years ago as a member of the Christian militia, the Lebanese Forces.

Had he kept his military field glasses "from the old days", wonders Badri.

"I wish; these are just cheap Chinese ones," comes the reply.

That the men, now in their fifties, can joke together is an indication of how far their personal journeys have taken them since the partly sectarian conflict ended in 1990.

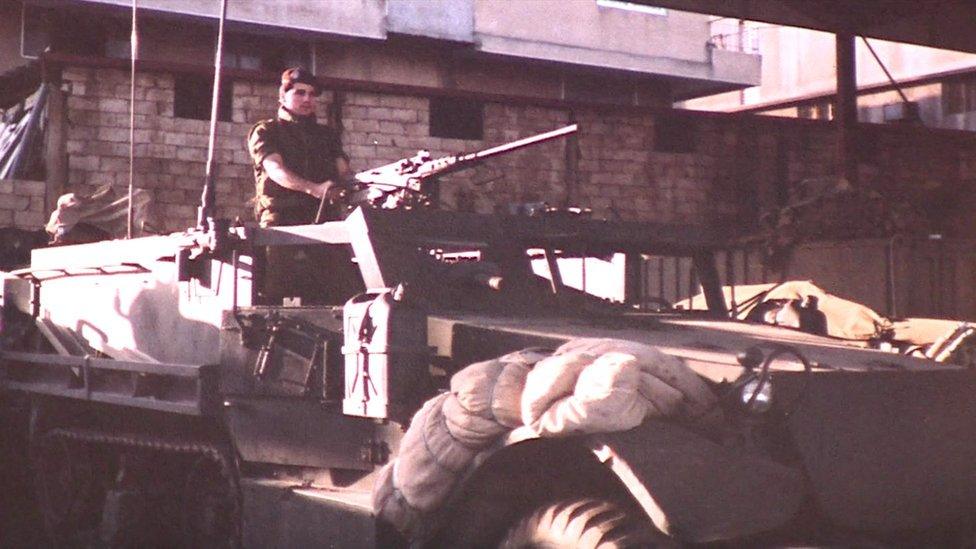

Badri, who's from the Druze religion, recalls the attitude to his friend's "isolationist" forces at the time he was head of the Progressive Socialist Party's armoured division.

"These were our enemies. We fought against their project for the country," he says.

The civil war had broken out in 1975 and was marked by sectarian divisions and foreign interference. It stretched on for 15 years, costing an estimated 150,000 lives, before a peace deal silenced the guns and transformed some militia leaders into prominent politicians. Many remain firmly in power.

Simmering tensions have persisted, with little closure for those who fought, or whose communities were torn apart.

"We fear the war might be back. We can see how tensions are still very high," says Antoun. Widening divisions between Muslim sects across the Middle East had made the situation even more complex, he added.

The former enemies met years after the conflict, at the suggestion of a mutual friend.

Badri had seen the effects of the war he waged, when he joined the government department tasked with dealing with the 500,000 people left displaced by the conflict.

"I could see first-hand the consequences of the war, the tragedies of the families, the scale of the destruction," he says. "That was something I could not see from the vantage point of a fighter."

"We realised there are no winners in a civil war," says Antoun. "We have grown to believe that violence leads nowhere."

It prompted the men to join Fighters for Peace, a Lebanese NGO set up in 2014 by former militiamen from different sects and affiliations. Its members reach out to younger generations, hoping to prevent them following in their footsteps. Most fighters were aged between 17 and 20 when they joined the civil war.

Antoun, left, was introduced to Badri by a mutual friend

"This is a very dangerous age," says Antoun. "Our aim is to tell the youth of this age - who are easily influenced by sectarian emotions - about our experience and its negative results. We want to pass to them the same message every fighter is passing to his own children."

There is no common narrative about the civil war, meaning it is not taught in schools, and youngsters learn the contrasting, disputed, versions passed on by their families.

At conferences and summer camps, the veterans offer first-hand accounts, testifying about their role, what they saw and their own transformation. They reach out to young fighters in security hotspots such as the northern city of Tripoli, which has been scarred by years of intermittent battles between Sunnis and Alawite Shia communities.

"We want them to avoid doing what we did," says Antoun.

At dialogue events, audiences are encouraged to share thoughts and stories about the war so that they can be brought to life through playback theatre.

At one such performance, a female actor recreates the childhood memories of a woman in her 40s, who was displaced by the war and recalls people stashing knives in their socks in case of attack. The performer describes the courage of Lebanon's displaced as they passed through dozens of areas carrying children in their luggage.

"This community was so fearless it used to sleep under a sky lit by grenades," she says, as musicians add atmosphere with percussion instruments and an oud. Two actors form a watchful cluster around her, as a third imitates the sound of a falling rocket.

The performances recreate personal experiences of loss, hatred, fear and trauma, turning the event into a collective catharsis. Under the watchful sight of ex-fighters, the participants cannot hold back their emotions.

Some in the audience cry, others burst out of the room. And, as the session goes on, more and more people raise their hands to tell a version of the war. Afterwards they reflect. To them, the war no longer follows a single narrative, and the picture has become one created from multiple perspectives.

"This is very powerful", says one woman as she approaches the veterans after the event. "You have to do this more often."

For the ex-fighters too, it's an intense exercise. One of them explains that the sessions often bring back memories, guilt and nightmares. But he adds: "They are very important and hopefully constructive."

As we leave the venue, Badri reflects: "We're not pretending that we can stop wars but at least we can leave an impact."

Crossing Divides

Crossing Divides: a week of stories about people creating connections in a polarised world.

How to survive a difficult conversation

Do you have experience of building bridges within divided communities? Share them with us by emailing haveyoursay@bbc.co.uk, external.

You can also contact us in the following ways:

Tweet: #CrossingDivides

WhatsApp: +44 7555 173285

Text an SMS or MMS to 61124 (UK) or +44 7624 800 100 (international)

Please read our terms & conditions

- Published10 January

- Published14 July 2017

- Published17 November 2015