Syria: What can Western military intervention achieve?

- Published

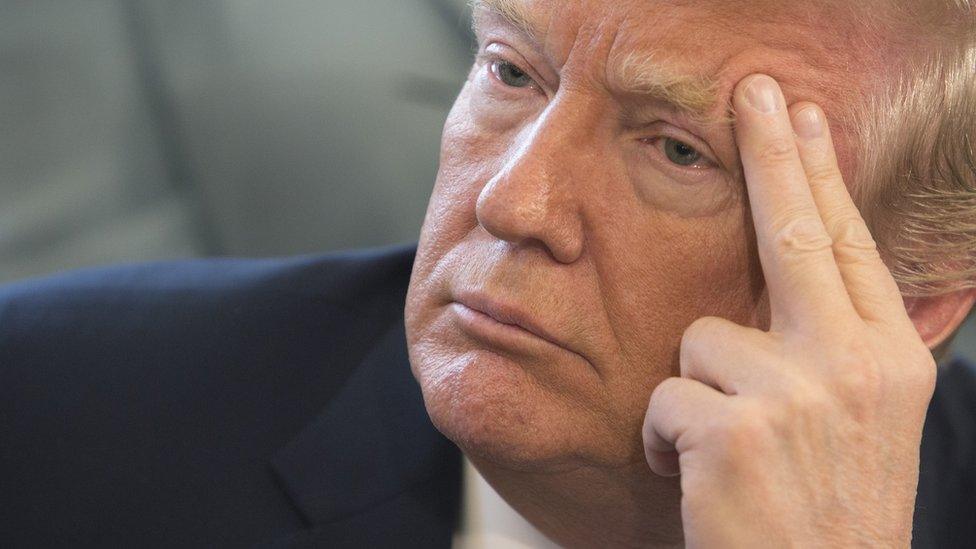

President Trump has signalled military intervention is likely in the near future

As the US and UK governments continue to discuss their potential response to the suspected chemical weapons attack in Douma in Syria, what could military intervention achieve?

The critical military virtue of surprise has long since disappeared for the United States and its allies in the strikes it is planning against Syrian military facilities.

Indeed, Syrian forces have had more than two days to move their aircraft and other military assets into Russian bases at Latakia, Tartus and Khmeimim, where they will be within the protective bubbles of Russia's highly capable S-400 surface-to-air missiles.

The Syrians have emptied their infantry bases and dispersed as much of their armed forces as possible, in anticipation of incoming Western missiles.

The Russians will undoubtedly try to protect their bases, if attacked, so the situation is fraught with superpower brinkmanship and the danger of accidental conflict.

For Western military planners the two greatest questions are what can they achieve militarily in this situation, and what strategic difference can it make?

With Syrian forces forewarned, dispersed and under Russian protection, Western strikes will have to concentrate on Syria's fixed military facilities - bombing runways, destroying buildings and capital equipment where it remains in place.

The US president has said "nothing's off the table" - so what options are on the table?

Western attacks will probably try to destroy Syria's military command and control system, possibly with bunker-busting bombs and deep penetration warheads. They are likely to try to dismantle the military infrastructure that Syria has effectively rebuilt since 2015.

More ambitiously, and also more risky, the United States might declare a longer-term policy of revisiting these targets to keep them out of use and have Syrian aircraft bottled up inside their Russian bases - in effect trying to operate a quasi "no-fly zone" in Syria, at least for a while.

In April 2017 the US launched 59 cruise missiles at the Shayrat airbase in response to a previous chemical weapons attack

Last year when the US struck President Assad's Shayrat airbase in retaliation for the use of chemical weapons in Khan Sheikhoun, the Syrian air force made sure it was seen to be back in action within a day. The US will be determined that this does not happen again, which is why we can expect this to be a more prolonged air campaign with repeated attacks on key sites.

What strategic purpose can be served by this?

It certainly won't make any immediate difference to the civil population of Syria, who have suffered so much at the hands of their own government, and the multitude of rebel, terrorist and guerrilla groups, some of whom have intimidated, as much as they have represented, them.

And President Assad is unlikely to relent in his determination to consolidate his hold on the country.

So why take all the risks of escalation with Russia and the prospects of unintended consequences that normally follow?

On its own, military force is meaningless. It has to be part of a political strategy and in this case the strategy is about bigger issues than Syria itself and only offers a long-shot hope for the Syrian population.

The first objective is to push back against the increasing "normalisation" of chemical weapons being used in wars of any kind.

The taboo against them has been surprisingly strong since the end of World War One. The Chemical Weapons Convention of 1993, external has been one of the most effective disarmament measures in modern history. Syria is a signatory to it.

In 2013 President Obama claimed he would uphold that taboo as a "red line", but then didn't. And despite firm denials from the Assad government, there is an abundance of evidence that Syrian forces, with Russian connivance, have been using chemical weapons against their own people on a regular basis ever since.

Many Western politicians feel that - with all the moral grey areas of this situation - they cannot sell the pass on this issue yet again. It has become a test case for the international rule of law, which is under severe pressure on many fronts.

The World Health Organization has demanded "unhindered access" to Douma in Syria to verify claims about the attack

Beyond that, some argue effective military action would represent an acceptance that Western powers have got to get back into the game of Middle East politics at a time when the region is melting down.

The campaign against so-called Islamic State (IS) was always a geopolitical sideshow, and Western influence on what has been happening from Lebanon to the Yemen has been in steep decline.

Of course, it is tempting, and understandable, for Western leaders to want to leave it all alone. But while they took their eye off the ball fighting IS, the future of the area was being determined by Iran, Russia and partly also by Turkey.

The calculation is whether long-term Western interests are served better by involvement than indifference to a constellation of powers that is sliding out of control.

And the hope for the Syrian population is that an effective military campaign could possibly push President Assad back into negotiations so that the war might end with something more humane than a vicious victory.

Using military force is never easy, but it can only be effective if it is part of a coherent and realistic political strategy.

About this piece

This analysis piece was commissioned by the BBC from an expert working for an outside organisation.

Professor Michael Clarke, external is a senior research fellow at the Royal United Services Institute for Defence and Security Studies (Rusi), and associate director of the Strategic Studies Institute.

Edited by Jennifer Clarke.

- Published12 April 2018

- Published13 April 2018

- Published12 April 2018

- Published12 April 2018

- Published11 April 2018

- Published11 April 2018

- Published10 July 2018