Saudi Arabia's enduring male guardianship system

- Published

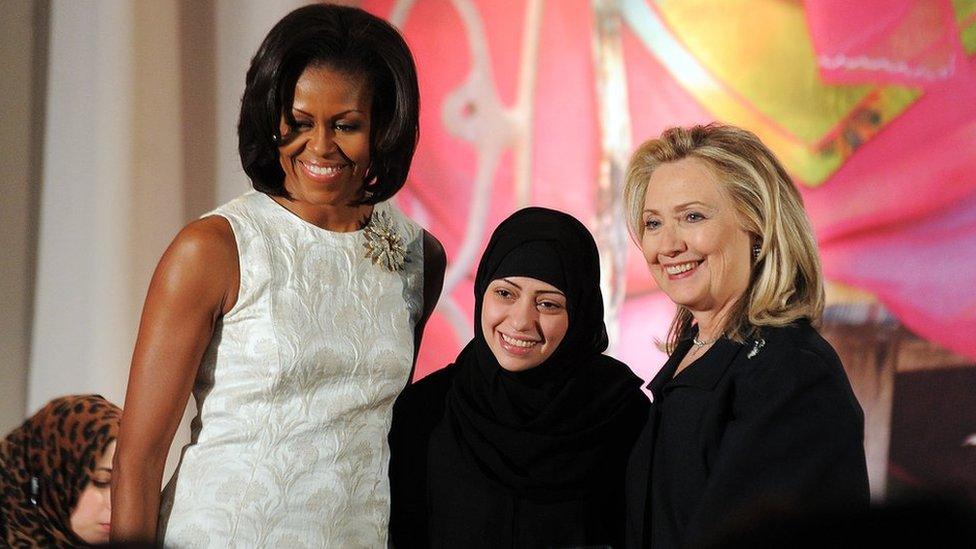

Samar Badawi, pictured with Michelle Obama and Hillary Clinton, has campaigned for equality

Saudi Arabia drew international plaudits last year when it lifted a longstanding ban on women driving.

However, restrictions on women remain - most notably, the "male guardianship system", a woman's father, brother, husband or son has the authority to make critical decisions on her behalf.

These restrictions were highlighted in early January, when a young Saudi woman fleeing her family barricaded herself in a hotel room in Bangkok saying she feared imprisonment if she was sent back home.

A Saudi woman is required to obtain a male relative's approval to apply for a passport, travel outside the country, study abroad on a government scholarship, get married, leave prison, or even exit a shelter for abuse victims.

"This is something that affects every Saudi woman and girl, from birth to death. They are essentially treated like minors," the Egyptian-American journalist Mona Eltahawy told the BBC.

Saudi Arabia ratified the United Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women in 2000, external and has said gender equality is guaranteed in accordance with the provisions of Sharia, or Islamic law, external.

The conservative Gulf kingdom has also reversed a ban on sports for women and girls in public schools, and allowed women to watch football matches in stadiums.

However, UN experts expressed concern in February 2018 at the country's failure to adopt a specific law prohibiting discrimination against women, external, as well as the absence of a legal definition of discrimination against women.

The male guardianship system, the experts noted, was "the key obstacle to women's participation in society and economy".

Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman and his father King Salman have introduced some reforms

The system is said to be derived from the Saudi religious establishment's interpretation of a Koranic verse, external that says: "Men are the protectors and maintainers of women, because God has given the one more [strength] than the other, and because they support them from their means."

Human Rights Watch reported in 2016 that the kingdom "clearly and directly enforces guardianship requirements in certain areas", external, and a number of women who have challenged the system have faced detention and prosecution.

In 2008, the prominent rights activist Samar Badawi, whose father allegedly physically abused her, fled her family home and found refuge at a shelter. She then began legal proceedings to strip her father of her guardianship.

In retaliation, she said, her father filed a charge of "disobedience" against her, external. A judge ordered her detention in 2010 and she spent seven months in prison before activists drew attention to her case and the authorities dropped the charge.

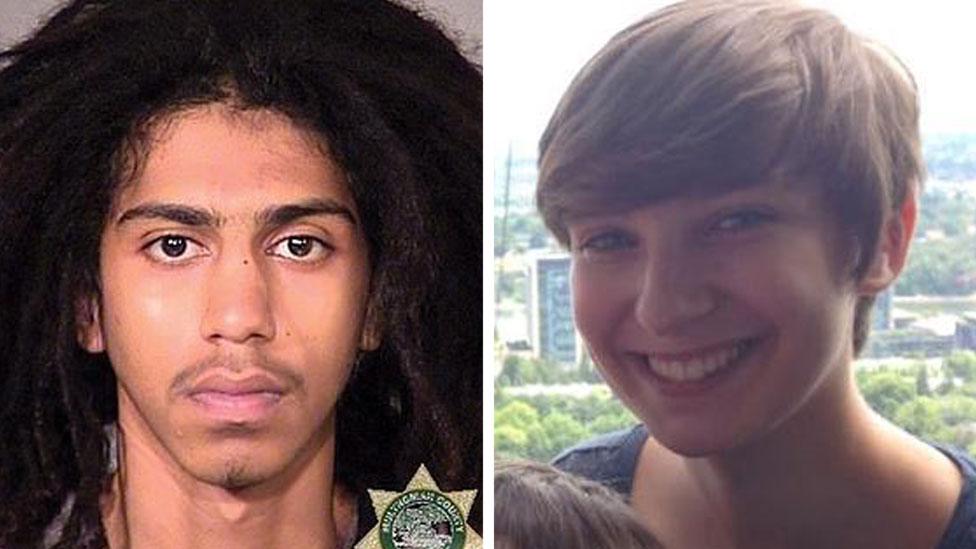

Mariam al-Otaibi was detained for 100 days after she fled her father's house

Mariam al-Otaibi, another activist, spent three months in detention in 2017, external after her father accused her of "disobedience".

She had fled her home after allegedly facing abuse from her father and brother in retaliation for leading social media campaigns against the guardianship system.

Her eventual release from prison was hailed as a victory by fellow activists because it took place without a male guardian.

Even women who have fled abroad have been unable to avoid detention.

In 2017, Dina Ali Lasloom was forcibly returned to her family in Saudi Arabia while in transit in the Philippines en route to Australia. She had said she was escaping a forced marriage.

Human Rights Watch said it received reports that Ms Lasloom was detained in a shelter for some time. It is not clear if she has since been returned to her family.

(June 2018) Saudi women hit the road

Women's rights activists have long called for an end to the guardianship system.

In September 2016 they handed over a petition containing 14,000 signatures to the Royal Court, after the Arabic hashtag "Saudi women want to abolish the guardianship system" went viral on Twitter and sparked a large-scale campaign.

The Grand Mufti, Abdulaziz Al Sheikh, described the petition as a "crime against the religion of Islam and an existential threat to Saudi society", but five months later King Salman issued a decree allowing women to access government services without being required to obtain a male guardian's approval, external.

And in September 2017, the king announced that women would be allowed to drive for the first time. Activists celebrated the news, but also vowed to step up their campaign for equality.

Then in May 2018 - just weeks before the driving ban was lifted - the Saudi authorities began an apparent crackdown on the women's rights movement that saw more than a dozen activists detained, external, including Ms Badawi. Men who had supported their cause or defended them in court were also arrested.

Several of those detained were accused of serious crimes, including "suspicious contact with foreign parties", that could entail lengthy prison terms. Government-aligned media outlets meanwhile branded them "traitors".

- Published21 November 2018

- Published13 June 2018

- Published16 November 2017

- Published15 November 2018

- Published24 December 2018

- Published1 June 2017

- Published12 April 2017