Trumplomacy: Where are things at with the Mideast peace plan?

- Published

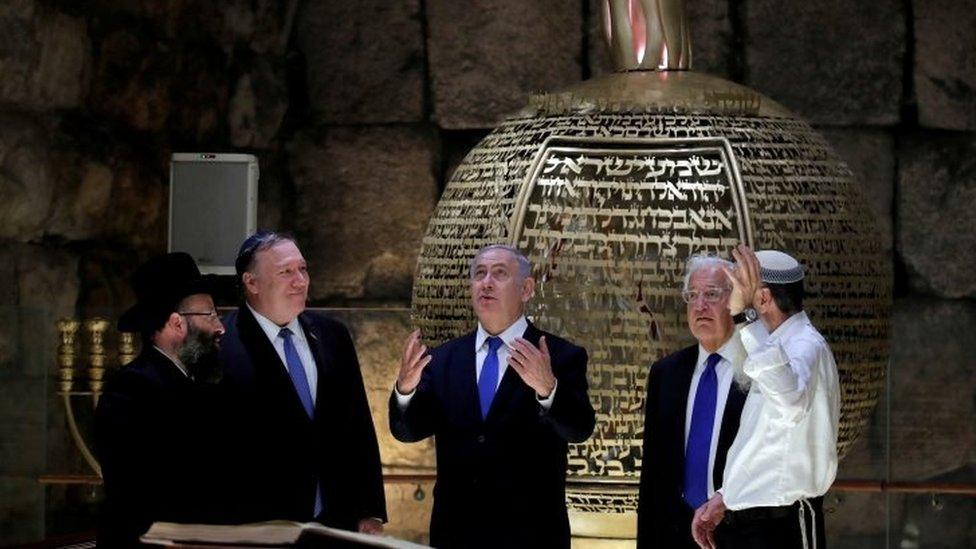

Secretary of State Mike Pompeo (R) recently became the first high-ranking US official to visit Jerusalem's Western Wall last month

With a newly elected right-wing government taking shape in Israel this is a good time to check in on the status of the Trump administration's peace plan.

The Secretary of State, Mike Pompeo, did his best to reveal as little as possible about what President Donald Trump calls "the deal of the century" during questioning by four different congressional committees over the past two weeks. But his testimony was instructive nevertheless.

In terms of the timing, the plan will be rolled out anywhere from "before too long" to "less than 20 years", he said. The speculation in Israeli newspapers is mid-June, after the Jewish and Muslim holidays.

What is the new policy?

Crucially, Mr Pompeo suggested the initiative would not propose the creation of a Palestinian state, which has been the cornerstone of US policy for more than two decades.

He did not say so directly.

But he appeared to wrap the "two-state solution" into what he called a "failed, old set of ideas not worth re-treading".

He continually deferred to the two parties to make the decision themselves, despite insistent demands from US Democratic lawmakers to spell out the Trump administration's position.

Even more alarming for them, he did not voice opposition to a unilateral annexation of all or parts of the occupied Palestinian West Bank by Israel, something Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has said he would do.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu (centre) hosted Mr Pompeo last month

And he made clear that the administration's approach was to "recognise realities."

That's a useful steer, especially as the realities it has recognised so far are Israeli ones.

How has the policy changed?

Remember that the formula for peace negotiations has been: two states based on the borders of Arab territory seized by Israel in the 1967 war, with mutually agreed land swaps; sufficient security arrangements; a just solution for Palestinian refugees; and negotiations to settle the fate of Jerusalem, the occupied eastern part of which Palestinians claim as their capital.

But the White House has declared that Jerusalem is the capital of Israel, cut funds to the UN agency that looks after Palestinian refugees, and accepted Israel's unilateral annexation of other occupied territory, the Golan Heights.

The state department's new envoy to combat anti-Semitism, Elan Carr, has reinforced this Israeli narrative in US policy.

He told us that boycotting goods made in Jewish West Bank settlements was anti-Semitic, even though the settlements are illegal under international law and have expanded to such a degree many question whether a Palestinian state is still viable.

"Refusing to buy products made by Jewish communities and wanting to buy products made by Arab communities that live next door to each other seems to me to be discriminatory," he said.

What's the response been?

The administration's embrace of the Israeli government's right-wing positions has alarmed liberal American Jewish organizations.

"What they've done so far tells you what they intend to lay out," says Jeremy Ben-Ami of the J Street lobby group. "They have no intention to lay out what could conceivably resolve the conflict. Instead they will tie American government positions to those of the farthest right of Israel's political spectrum."

On the basis of actions so far the Palestinian Authority, led by Mahmoud Abbas, has boycotted the American efforts, much to the frustration of the plan's architect, President Trump's son-in-law and advisor Jared Kushner.

Mr Kushner, who is Jewish, is deeply interested in US-Israel relations, which is reportedly why the president put him in charge of trying to find a solution to the intractable conflict.

He and Mr Pompeo have said that their strategy seeks to make life better for Palestinians, and that both sides will be called on to make compromises.

Details are closely guarded, but what has leaked out in various reports is an emphasis on billion dollar boosts to the Palestinian economy from Gulf Arab states, a preference for Palestinian autonomy rather than statehood, and the cementing of Israel's military dominance of the West Bank.

What about the Palestinian reaction?

A recent poll, however, showed that a large majority of Palestinians supported their leadership's rejection of the initiative, because they believe there's no intention to meet any of their basic national demands.

Mr Abbas is very unpopular. But on a recent trip to Jerusalem I was told anecdotally that Palestinians have at least given him credit for standing firm on their three core issues: Jerusalem, refugees and maintaining funds to Palestinian prisoners - whom the Israelis regard as terrorists - despite financial pressure.

Under robust questioning in congress Mr Pompeo did acknowledge that to work, the peace plan would have to be acceptable to both the Israelis and the Palestinians.

"To be a peaceful resolution," he said, "the Palestinian people will have to agree that it makes sense."

By that standard all indications so far are that it will be a failure. But we await to see what the unveiling will bring, whether in two months or 20 years.

- Published22 March 2019

- Published22 March 2019

- Published21 March 2019