Russia, Turkey and Syrian government on the same page - but for how long?

- Published

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan meeting Vladimir Putin in Sochi

The diplomatic and military choreography tells the story in a nutshell.

Russian President Vladimir Putin meets his Turkish opposite number to underscore Moscow's role as the would-be guarantor of stability in the region. Russia and Turkey will soon be mounting joint patrols to help delineate the boundary of the new, so-called security zone. Meanwhile, withdrawing US special forces vehicles are pelted with vegetables and rubbish as they leave their erstwhile Kurdish allies to their fate.

The Turkish incursion into Syria and the US retreat have huge implications for both Syria itself and the region at large. Some of the impact is immediate and some potentially long-term.

This is, in the first instance, a victory for the Turks, for Russia and for the Syrian government. Turkey has on the face of things got a large part of what it wanted. It keeps its troops and allied militias in those areas of Syria that it already controls. Russia and Syria appear to have agreed to ensure the departure of Kurdish forces from a broad swathe of territory running across almost the whole frontier zone.

Russia has translated its long-running military support for the Syrian regime into its newly found status as the essential external player in Syria: the only actor capable of brokering this kind of deal. Russia is back in the Middle East and whatever the morality of some of its air operations over Syria, it has demonstrated - unlike the US - that it is a reliable ally that can get results.

For the Syrian government too there is good news. President Bashar al-Assad extends his control northwards, though he has had to accept a Turkish presence on Syrian territory. It is yet one more stage in securing a victory for the Syrian regime that, at the outset of the civil war, most analysts saw as unlikely, if not impossible.

Turkey, Russia and Syria may be on the same page for now. But will this last? Is Turkey's hold over Syrian territory going to become permanent? What say will the Kurds have? They are at a huge disadvantage but will they meekly succumb to the joint Russian-Turkish diktat? What, if any, alternative do they have?

The Turkish incursion into northern Syria has huge implications for the region

If the Kurds are the most obvious immediate losers, the United States has experienced a major diplomatic setback. President Donald Trump may be right in that ending foreign wars, in the abstract, is a popular idea back home. But there are ways and means of doing this. A precipitate departure of US forces, leaving an ally in peril, sends all the wrong signals at a time when US prestige and reliability in the region are already being called into question.

Washington's handling of the alleged Iranian attacks on Saudi oil installations underscored the problem. The attack, which demonstrated the vulnerability of a key element of the Saudi economy, passed without any clear US response. Washington appeared happy for the Saudis to take the lead in the crisis and the belated reinforcement of their air defences with US aircraft and missile batteries probably came too late to restore the Saudis' shattered confidence.

To many in the Gulf and in Israel, President Trump speaks boldly but has no follow-through. More broadly, and this is something that many US commentators and diplomats have discussed, the president's transactional approach to foreign affairs seems to lack any strategic dimension.

Contrast this with Mr Putin's approach. He has sought to leverage a relatively modest military contribution that propped up the Assad government and has thus transformed Russia into a key player in the region's diplomacy, enticing towards his orbit a key Nato member, Turkey, which on Syria policy has long been unhappy with Washington's dalliance with the Kurds. The fact that Russia's gains have largely come from Washington's failures does little to change the balance of strategic advantage.

Indeed, Russia's ability to play upon Turkish discontent with its existing allies adds another element to the mix. Turkey's behaviour is giving the Nato alliance an uncomfortable 70th birthday. Nato representatives have, somewhat uncomfortably, gone out of their way to express their understanding of Turkey's security concerns. But it is clear Turkey is currently on a trajectory that is taking it away from Nato (and some would say from the West in general). This is, after all, the Turkey that earlier this year purchased an advanced Russian surface-to-air missile system - an almost unthinkable step from a Nato member.

The Kurdish Internal Security force stood guard during a protest against the Turkish assault in north-eastern Syria on Wednesday

If Washington's strategic drift continues, then the long-term impact of these events could be considerable and work in contradictory directions. In the Gulf, the response of the Saudis and their allies seems to be cautiously to explore some kind of rapprochement with Iran. In Israel by contrast, it could make a looming conflict with Tehran more likely. Iran may judge that the US no longer has Israel's back in quite the same way. And there is little doubt that the US withdrawal from Syria has prompted some significant strategic re-thinking in Israel.

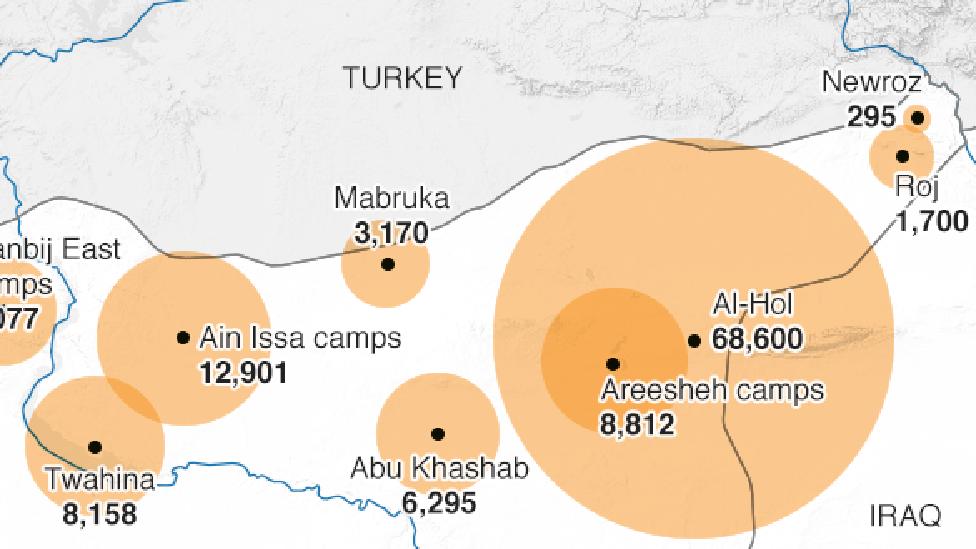

Another huge unknown is what impact the upheavals in north-eastern Syria will have on the fate of the Islamic State (IS) group. Clearly the major Western fear is that there will be a resurgence of IS violence as fighters escape camps or detention centres.

Will these locations continue to be secured? And to what extent will the Turks, the Syrians and the Russians be able to cope if there is such a resurgence?

This is a snapshot response to a complex set of events. For now Russia is undoubtedly up and the US is undoubtedly down. But even among those countries who seem to see eye to eye, there are fissures. Turkey has not got everything it wanted. Russia has a bumpy history with Turkey, as indeed does Syria. Iran, Syria's other key ally, is by no means happy at the Turkish incursion.

There remains considerable room for friction.

- Published17 October 2019

- Published17 October 2019

- Published14 October 2019

- Published15 October 2019

- Published23 October 2019

- Published22 October 2019

- Published19 September 2019

- Published17 September 2019