Who was Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi?

- Published

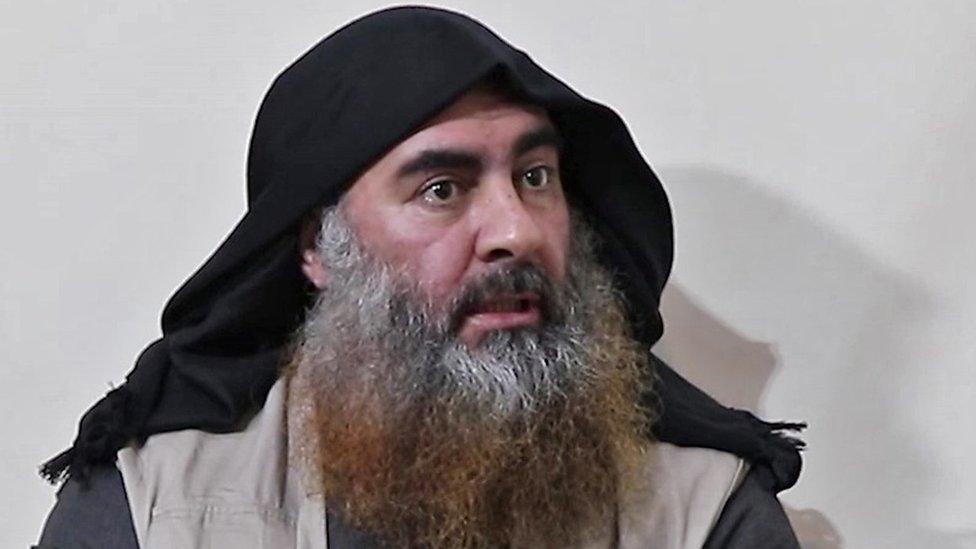

Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi last appeared on camera in a video released in April 2019

Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the leader of the jihadist group Islamic State (IS) and arguably the world's most wanted man, killed himself during a raid by US commandos in north-western Syria, President Donald Trump has said.

The self-styled "Caliph Ibrahim" had a $25m (£19m) bounty on his head and had been pursued by the US and its allies since the rise of IS five years ago.

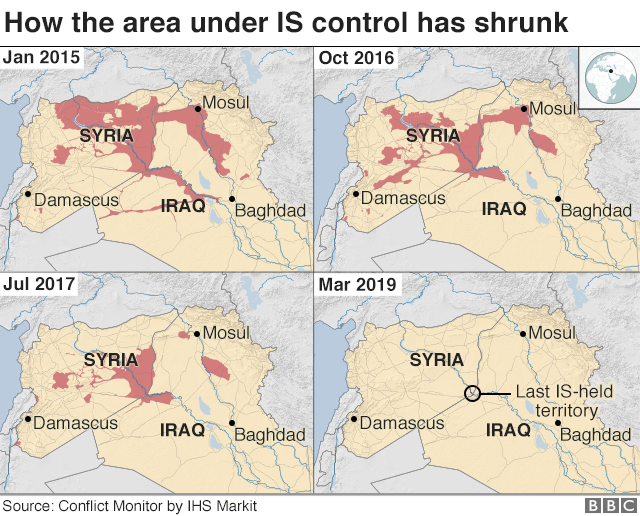

At its peak, IS controlled 88,000 sq km (34,000 sq miles) of territory stretching from western Syria to eastern Iraq, imposed its brutal rule on almost eight million people, and generated billions of dollars in revenue from oil, extortion and kidnapping.

But despite the demise of its physical caliphate and its leader, IS remains a battle-hardened and well-disciplined force whose enduring defeat is not assured.

'The believer'

Baghdadi - real name Ibrahim Awwad Ibrahim al-Badri - was born in 1971 in the central Iraqi city of Samarra.

His religious Sunni Arab family claimed to be descended from the Prophet Muhammad's Quraysh tribe - something generally held by pre-modern Sunni scholars as being a key qualification for becoming a caliph.

As a teenager, he was nicknamed "the believer" by relatives, external because of the time he spent at the local mosque learning how to recite the Koran and because he would often chastise those failing to abide by Islamic law, or Sharia.

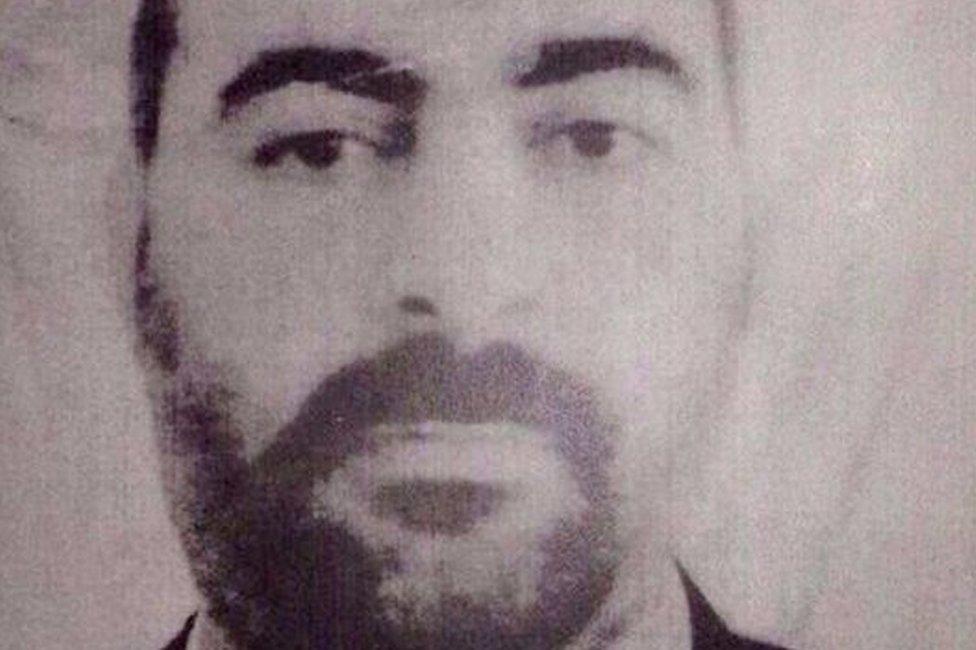

Ibrahim Awwad Ibrahim al-Badri was born in 1971 in Samarra, Iraq

After finishing school in the early 1990s he moved to the capital, Baghdad. He gained bachelor's and master's degrees in Islamic studies before embarking on a PhD at the Islamic University of Baghdad, according to a biography published by supporters.

While a student, he lived near a Sunni mosque in Baghdad's north-western Tobchi district. He is said to have been a quiet man who kept to himself, except for when he taught Koranic recitation and played football for the mosque's club. Baghdadi is also believed to have embraced Salafism and jihadism during this time.

'Jihadist university'

Following the US-led invasion that toppled President Saddam Hussein in 2003, Baghdadi reportedly helped found an Islamist insurgent group called Jamaat Jaysh Ahl al-Sunnah wa-l-Jamaah that attacked US troops and their allies. Within the group, he was the head of the Sharia committee.

In early 2004, Baghdadi was detained by US troops in the city of Falluja, west of Baghdad, and was taken to a detention centre at Camp Bucca in the south.

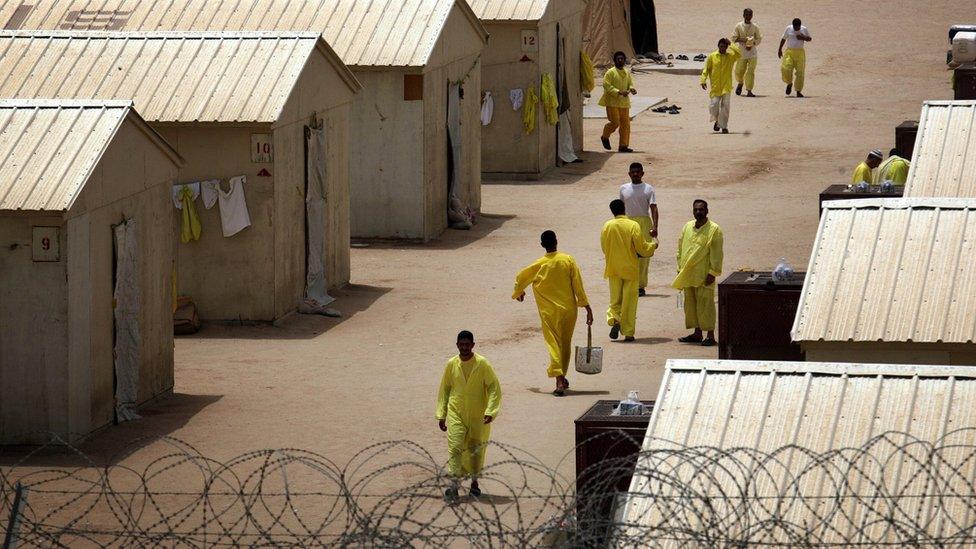

Baghdadi was detained by US forces at Camp Bucca for 10 months

Camp Bucca became what has been described as a "university" for the future leaders of IS, with inmates becoming radicalised and developing important contacts and networks.

Baghdadi reportedly led prayers, delivered sermons and taught religious classes while in detention, and was sometimes asked to mediate in disputes by the prison's US administrator, external. He was considered a low-level threat by the US and was released after 10 months.

"He was a street thug when we picked him up in 2004," a Pentagon official told the New York Times in 2014, external. "It's hard to imagine we could have had a crystal ball then that would tell us he'd become head of [IS]."

Rebuilding al-Qaeda in Iraq

After leaving Camp Bucca, Baghdadi is believed to have come into contact with the newly formed al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI). Under the leadership of the Jordanian Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, AQI became a major force in the Iraqi insurgency, external and gained notoriety for its brutal tactics, including beheadings.

In early 2006, AQI created a jihadist umbrella organisation called the Mujahideen Shura Council, which Baghdadi's group pledged allegiance to and joined.

Baghdadi joined the jihadist insurgency that plagued Iraq after 2003

Later that year, following Zarqawi's death in a US air strike, the organisation changed its name to the Islamic State of Iraq (ISI). Baghdadi supervised the ISI's Sharia committees and joined its consultative Shura Council.

When ISI's leader Abu Umar al-Baghdadi died in a US raid in 2010 along with his deputy Abu Ayyub al-Masri, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi was named his successor.

He inherited an organisation that US commanders believed to be on the verge of a strategic defeat. But with the help of several Saddam-era military and intelligence officers, among them fellow former Camp Bucca inmates, he gradually rebuilt ISI.

'Caliph Ibrahim'

By early 2013, it was once again carrying out dozens of attacks a month in Iraq. It had also joined the rebellion against President Bashar al-Assad in Syria, sending Syrian militants back from Iraq to set up the al-Nusra Front as al-Qaeda's affiliate in the country. There, they found a safe haven and easy access to weapons.

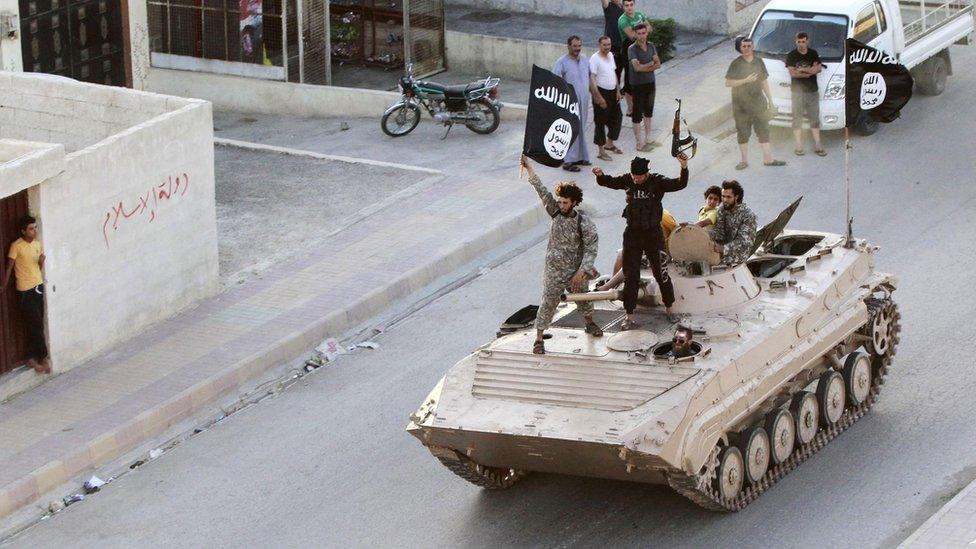

Supporters of IS celebrated the proclamation of a caliphate in Raqqa in June 2014

That April, Baghdadi announced the merger of his forces in Iraq and Syria and the creation of "Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant" (Isis/Isil). The leaders of al-Nusra and al-Qaeda rejected the move, but fighters loyal to Baghdadi split from al-Nusra and helped Isis remain in Syria.

At the end of 2013, Isis shifted its focus back to Iraq and exploited a political stand-off between the Shia-led government and the minority Sunni Arab community. Aided by tribesmen and former Saddam Hussein loyalists, Isis overran Falluja.

In June 2014, several hundred Isis militants overran the northern city of Mosul, routing the Iraqi army, and then advanced southwards towards Baghdad, massacring their adversaries and threatening to eradicate the country's many ethnic and religious minorities.

In July 2014, Baghdadi was filmed giving a sermon at a mosque in Mosul

At the end of the month, after consolidating its hold over dozens of Iraqi cities and towns, Isis declared the creation of a "caliphate" - a state governed in accordance with Sharia by a caliph - and renamed itself "Islamic State". It proclaimed Baghdadi as "Caliph Ibrahim" and demanded allegiance from Muslims worldwide.

Five days later, a video was released showing Baghdadi delivering a sermon at Mosul's Great Mosque of al-Nuri - his first public appearance on camera.

Experts said Baghdadi's sermon evoked the letters and speeches of caliphs in the first centuries of Islam, external. He enjoined Muslims to emigrate to IS territory in order to carry out a war for the faith against unbelievers. Tens of thousands of foreigners went on to heed the call.

UN investigators accused IS of committing genocide against Yazidis in Iraq

Just over a month later, IS militants advanced into areas controlled by Iraq's Kurdish ethnic minority and killed or enslaved thousands of members of the Yazidi religious group.

The atrocities against the Yazidis, which UN human rights investigators said constituted the crime of genocide, prompted a US-led multinational coalition to launch an air campaign against the jihadists in Iraq. It started conducting air strikes in Syria that September, after IS beheaded several Western hostages.

IS welcomed the prospect of direct confrontation with the US-led coalition, viewing it as a harbinger of an end-of-times showdown between Muslims and their enemies described in Islamic apocalyptic prophecies.

In the areas under its control, IS implemented an extreme interpretation of Islamic law that terrorised residents. Women accused of adultery were stoned to death, thieves had their hands amputated, and those accused of opposing IS rule were beheaded or crucified. A Jordanian pilot whose plane came down near Raqqa, Lt Moaz al-Kasasbeh, was burned alive.

A Raqqa resident describes daily life under so-called Islamic State.

The group sparked global outrage by destroying many of the region's most famous archaeological sites, from the Syrian desert city of Palmyra to the Assyrian capital of Nimrud in Iraq, and looting artefacts from museums. The UN cultural agency, Unesco, condemned the wanton destruction as a war crime.

Attacks in other countries also began to be attributed to IS or individuals it inspired. Such attacks - including the downing of a Russian airliner over Egypt's Sinai peninsula in October 2015, the Paris attacks that November, and the Sri Lanka suicide bombings in April 2019 - have claimed several thousand lives since 2014.

Baghdadi was personally accused by the US of repeatedly raping an American NGO worker held hostage by IS, Kayla Mueller, and then having her killed. Officials said they learned about the abuse from two enslaved Yazidi girls.

IS defeated

Once the US-led coalition intervened, IS began to be slowly driven out of the territory it controlled.

The Iraqi city of Mosul was retaken by Iraqi government forces in July 2017

The ensuing war left many thousands of people dead across the two countries, displaced millions more, and devastated entire areas.

In Iraq, federal security forces and Kurdish Peshmerga fighters were supported by both the US-led coalition and a paramilitary force dominated by Iran-backed militias, the Popular Mobilisation (al-Hashd al-Shaabi).

In Syria, the US-led coalition backed an alliance of Syrian Kurdish and Arab militias, the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), and some Syrian Arab rebel factions in the southern desert. Troops loyal to President Assad meanwhile also battled IS with the help of Russian air strikes and Iran-backed militiamen.

Throughout the fighting the question of whether Baghdadi was dead or alive remained a source of mystery and confusion.

In June 2017, as Iraqi security forces battled the last remaining IS militants in Mosul, Russian officials said there was a "high probability" that Baghdadi was killed in a Russian air strike on the outskirts of the northern Syrian city of Raqqa, the de facto IS capital.

But that September IS released an audio message apparently from Baghdadi that included a call for the group's followers to "fan the flames of war on your enemies".

US-backed Syrian Democratic Forces fighters captured the city of Raqqa in October 2017

Such exhortations were not enough to stop SDF fighters capturing Raqqa the following month and driving its supporters into sparsely populated desert areas.

It was not until August 2018 that Baghdadi issued a new audio message. He urged followers in Syria to "persevere" in the face of its defeats on the battlefield.

The following month, the SDF launched the final stage of its campaign to clear IS from eastern Syria, targeting a strip of land running along the River Euphrates around the town of Hajin where tens of thousands of IS militants and their families had gathered after fleeing Mosul and Raqqa.

There was no indication that Baghdadi was among them, but unconfirmed reports emerged later saying that he had been forced to flee to Iraq's western desert after a faction within IS tried to oust him, external.

Thousands of suspected IS supporters and their families were detained in Baghuz

In March 2019, the last piece of territory held by IS in Syria, near the village of Baghuz, was captured by the SDF, bringing a formal end to Baghdadi's "caliphate".

US President Donald Trump praised the "liberation" of Syria, external, but added: "We will remain vigilant against [IS]."

'Battle of attrition'

IS was thought to still have thousands of armed supporters in the region, many of them operating in sleeper cells. In Iraq, they were already carrying out attacks in an attempt to undermine the government's authority, create an atmosphere of lawlessness, and sabotage reconciliation and reconstruction efforts.

In April 2019, Baghdadi appeared in a video for the first time in almost five years. But rather than speaking from a mosque pulpit in Mosul, this time he was sitting cross-legged on the floor of a room with a rifle by his side.

Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi has not been seen on video for five years

He acknowledged his group's losses and said IS was now waging a "battle of attrition", urging supporters to launch attacks to drain its enemies' human, military, economic, and logistical resources.

It was not clear when or where the video was recorded, but Baghdadi seemed to be in good health. He was seen sitting with at least three other men whose faces were masked or blurred, and going through files on IS branches elsewhere in the world.

Analysts saw it as an attempt by Baghdadi to assert that he was still in charge.

No more was heard from him until September, when IS released a purported audio message in which he said "daily operations" were under way on "different fronts".

He also called on supporters to free the thousands of suspected IS militants and tens of thousands of women and children linked to IS who were detained at SDF-run prisons and camps in Syria following the fall of Baghuz.

US special forces targeted a compound in Syria's Idlib province on 22 October

The following month, a Turkish military offensive against the SDF in north-eastern Syria and President Trump's decision to pull US troops out of the region in response sparked alarm that IS might be able to exploit the security vacuum.

More than 100 prisoners escaped during the offensive and IS sleeper cells carried out several attacks, but Mr Trump rejected criticism of the US withdrawal, external. "Turkey, Syria, and others in the region must work to ensure that [IS] does not regain any territory," he insisted. "It's their neighbourhood; they have to maintain it."

Early on 23 October, US special operations forces carried out a raid outside the village of Barisha, in the north-western Syrian province of Idlib, external - the last stronghold of the opposition to President Assad. The target of the raid was Baghdadi, despite the area being hundreds of kilometres from the place where he was believed to be hiding.

A resident of Barisha said the US helicopters fired missiles at two houses, flattening one

President Trump later told reporters that Baghdadi retreated into a tunnel with three of his children during the raid and then detonated an explosive vest when US military dogs were sent in, killing himself and the children. Baghdadi's body was mutilated by the blast, but test results gave certain and positive identification, he said.

"A brutal killer, one who has caused so much hardship and death, was violently eliminated - he will never again harm another innocent man, woman or child," Mr Trump declared. "He died like a dog. He died like a coward. The world is now a much safer place."

There was no immediate confirmation of Baghdadi's death from IS.