Iran protests: Who are the opposition in the country?

- Published

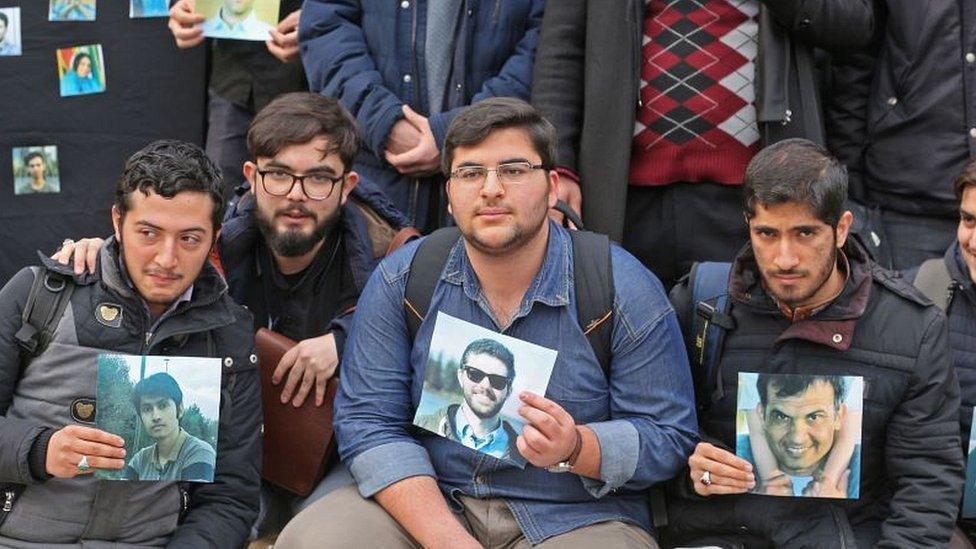

A protester in Tehran holds up a picture of one of the victims of the Ukrainian plane crash

There have been anti-government protests in the Iranian capital, Tehran, and other cities after the Iranian authorities admitted they had "unintentionally" shot down a Ukrainian International Airlines plane.

Some of the protesters have been heard shouting slogans against the leadership.

So how strong is opposition in Iran, and what do the protesters want?

Who are they protesting against?

The crowds taking to the streets in recent days have been concentrated in Tehran and other cities such as Isfahan, and comprise mainly university students and others from the middle classes, angered by the deaths of those on the plane.

They have condemned the authorities for not initially telling the truth. But slogans have also been heard against the Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Khamenei, and the Islamic regime.

Students in Tehran hold pictures of some of the plane crash victims

"Lots of them will have known people on that plane as they are students who can afford to travel abroad," says the BBC's Rana Rahimpour.

There is also little sign of these protests concentrating around a particular personality. "It's hard to say there's a single figurehead right now that people can unite around," says Fatemeh Shams, an Iranian professor at the University of Pennsylvania.

What political opposition is allowed?

Iran's system allows for elections, but political groups must operate within the strict boundaries of the Islamic Republic.

In the 2016 parliamentary elections, nearly half of the candidates were disqualified by Iran's Guardian Council, which vets them for their commitment to Iran's Islamic system.

And for this year's parliamentary elections, which are due to be held in February, thousands of potential candidates have again been disqualified, including 90 current lawmakers.

Any candidates from groups opposed to the Islamic Republic, or who want to change the existing system altogether, are not allowed to run.

Ayatollah Khamenei sits at the top of the Islamic Republic's political structure

The Guardian Council can also bar any would-be presidential candidates, and veto any legislation passed by parliament if it is deemed to be inconsistent with Iran's constitution and Islamic law.

Ayatollah Khamenei, who is positioned at the top of Iran's political power structure, appoints half of the members of this body.

The Supreme Leader also controls the armed forces and makes decisions on security, defence and major foreign policy issues.

So in practice, the president and the parliament in Iran - even if they support change - have limited powers.

There are also opposition movements who want greater autonomy for ethnic minorities like the Kurds, Arabs, Baluchis and Azerbaijanis.

Some of these groups - like the Democratic Party of Iranian Kurdistan - are armed and have fought for decades against the Iranian state.

Does the opposition have leaders?

There has been a movement pushing for reform in Iran for years, with Mohammad Khatami, the former president, as its figurehead.

In office from 1997 until 2005, Mr Khatami brought in limited social and economic reforms, and put out feelers to Western countries.

More extensive changes, however, were blocked by conservative interests, and Mr Khatami himself has been sidelined - with his movements and access to the media restricted.

Protests in 2009 turned into a major challenge to the regime

In 2009, a major challenge to the regime came after a disputed presidential election, won by hardliner Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.

Defeated candidates Mir Hossein Mousavi and Mehdi Karroubi challenged the result and became leaders of what was called the Green Movement. Millions took to the streets to demand a re-run of the election, but Ayatollah Khamenei insisted the result was valid.

Tough action against protests

There was a widespread crackdown against demonstrators that year and dozens of opposition supporters were reportedly killed. Many of the top opposition figures were detained. Mr Mousavi and Mr Karroubi remain under house arrest over a decade later.

More recently, there were protests at the end of 2017 and in early 2018 over worsening economic conditions.

High levels of unemployment in some parts of the country had hit the relatively young population particularly hard.

The wealthier middle classes also joined these protests against the handling of the economy by the government of President Hassan Rouhani, who is considered a moderate.

Those taking part shouted slogans against the country's leaders, and calls were heard for the restoration of the monarchy, overthrown in 1979.

Protesters took to the streets in 2019 as fuel price rises were introduced

Protests erupted again in November 2019 after the government announced it was raising petrol prices by 50% as it struggled to cope with economic sanctions reinstated by the US when it abandoned the nuclear deal the previous year.

The unrest prompted a bloody crackdown by the security forces.

Amnesty International said more than 304 people were killed, but a Reuters news agency report put the death toll at 1,500. The Iranian authorities dismissed both figures. An internet shutdown lasted for some five days, virtually cutting off the country.

A feature of these more recent protests is that they have often been leaderless, and fuelled by grassroots anger over inflation, unemployment and widening inequality.

However, despite outbreaks of unrest, the government has managed to remain in control, using a combination of severe restrictions on opposition figures and repressive actions.

- Published14 January 2020