Is Iran covering up its outbreak?

- Published

Iran is facing one of the largest coronavirus outbreaks in the world. Today, as families celebrate Persian New Year, Nowruz, there is concern the true scale of the virus is being downplayed by the government and could rapidly get much worse.

Mohammad has been working relentlessly since the coronavirus outbreak to save the lives of his patients. The hospital doctor, who works in the northern province of Gilan, has not seen his family for 14 days. He has lost colleagues. He has lost friends - including his former mentor, his teacher at medical school who recently fell victim to coronavirus.

"It's not just our hospital. The coronavirus outbreak has paralysed our whole health system," says Mohammad.

"The morale of staff is very low. Our families are so worried and we are under enormous pressure."

Mohammad's name has been changed because speaking out against the government in Iran risks arrest. But several doctors from across the country's northern provinces have spoken to the BBC about the dire conditions they are facing, and how badly they think the government has handled the crisis.

"We don't even have enough masks. Our medical staff are dying on a daily basis," says Mohammad.

"I do not know how many people died but the government is trying to cover up the true scale of the crisis. They lied in the early days of the outbreak."

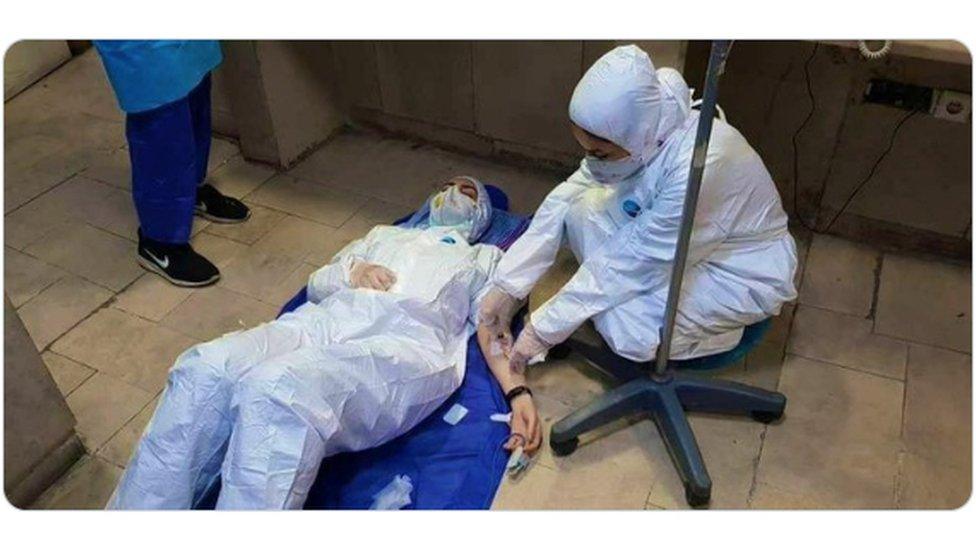

A medical professional supports a patient to hospital in Iran

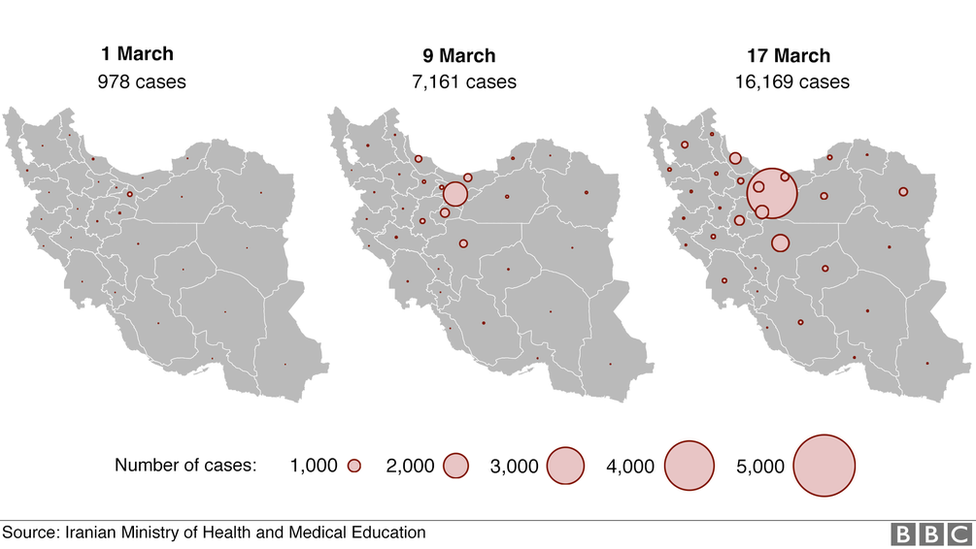

In just 16 days, Covid-19 spread throughout all 31 provinces in Iran.

On top of this, 16 countries claim they have cases of the virus that originated in Iran. They are Iraq, Afghanistan, Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Lebanon, the United Arab Emirates, Canada, Pakistan, Georgia, Estonia, New Zealand, Belarus, Azerbaijan, Qatar and Armenia.

However, critics of the authorities say the government of Iran has continued to downplay the outbreak.

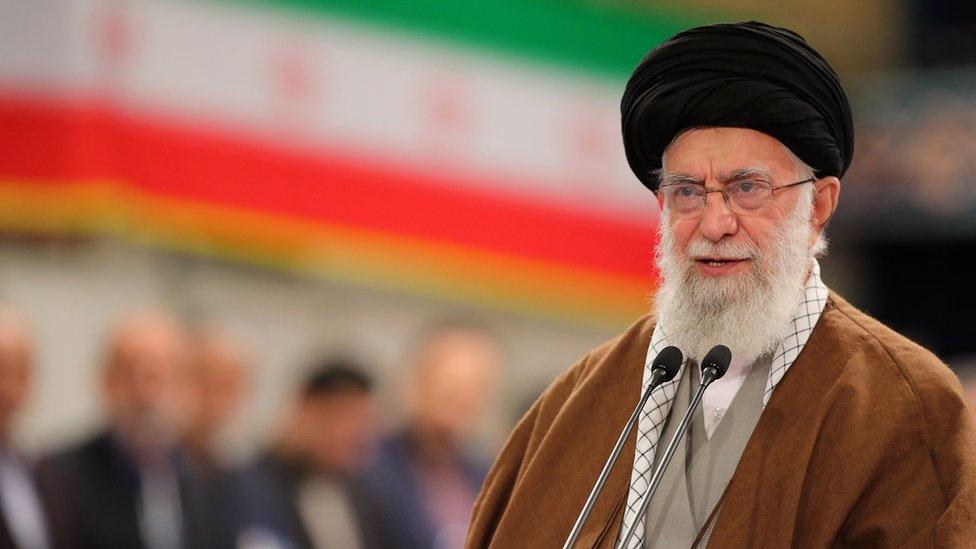

In its first announcement on 19 February, the government told people not to worry about the virus. Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei accused Iran's "enemies" of exaggerating the threat.

A week later, as the number of cases and deaths surged, President Hassan Rouhani echoed the Supreme Leader's words and warned against the "conspiracies and fear-mongering of our enemies". He said these were designed to bring the country to a standstill and urged Iranians to continue their everyday lives and carry on going to work.

Most recently, state-controlled TV programmes announced the coronavirus could be a US-manufactured "bioweapon", with the Supreme Leader tweeting about a "biological attack".

Iran's Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei

As of 20 March, nearly 1,300 people have died and nearly 18,000 people have been infected, according to the Iranian health ministry.

Iran is the third worst-hit country behind China and Italy.

Doctors from three of the worst-hit provinces in Iran - Gilan, Golestan and Mazandarn - have told the BBC that there are very few coronavirus testing kits, and medical supplies are limited - including basic medicines, oxygen tanks, sterilised masks, and protective scrubs and gloves.

Doctors are now having to kit out temporary field hospitals. One intensive care doctor described how her local football stadium was being equipped with beds to handle the overflow of patients.

Some factories in the capital Tehran are now producing medical equipment 24 hours a day

Every doctor the BBC spoke to said that based on their experience, the official statistics must be much lower than the reality.

One doctor, an A&E medic from Golestan Province, says her hospital receives an average of 300 patients a day. She estimates that 60%-70% of those are infected with coronavirus, but due to lack of resources, only those who are critically ill are admitted.

And only those who are admitted to hospital are counted in the official statistics.

The doctor describes having lost five patients a day on average over the past two weeks. She says that often by the time someone has arrived with a coronavirus testing kit, her patient has already died.

Medical staff bring in another patient suspected of Coronavirus

Also devastating for medical staff is the loss of their own. Medical professionals said they had recently lost a number of colleagues.

One heartbreaking case was that of 25-year-old Narjes Khanalizadeh, a nurse from the northern city of Lahijan who died towards the end of February.

A photo of her went viral on social media. But the government denied she had died of Covid-19.

Narjes Khanalizadeh collapsed on 23 February and died two days later

State-controlled TV channels continued to portray an image of easy-going and fearless medical staff working on the front line, courageously battling the virus and saving their patients.

But shortly after her death, the Iranian Nursing Organisation confirmed Narjes had died of coronavirus.

LATEST: Follow live updates

EASY STEPS: How to keep safe

A SIMPLE GUIDE: What are the symptoms?

TRAVEL PLANS: What are your rights?

IN-DEPTH: Coronavirus pandemic

How did the virus spread so fast?

According to the government, there were two "patient zeros", both of whom died in the city of Qom on 19 February. One, it said, was a businessman who contracted the disease in China.

Qom quickly became the epicentre of the outbreak.

The city is an important pilgrimage destination for Shia Muslims. It is home to the country's top Islamic clerics, and draws some 20 million domestic and around 2.5 million international tourists a year. Each week, thousands of pilgrims navigate the city, paying their respects by kissing and touching the numerous shrines and landmarks.

Imam Hasan Al-Askari Mosque in Qom has been closed since the outbreak

The virus spread quickly and the number of cases began to soar. But instead of quickly quarantining the city, representatives of the Supreme Leader - such as cleric Mohammad Saeedi - campaigned for pilgrims to keep on visiting.

"We consider this holy shrine to be a place of healing. That means people should come here to heal from both spiritual and physical diseases."

A masses kisses the closed door of the Fatima Masumeh shrine in reverence

Richard Brennan, director of emergency operations for the World Health Organization (WHO), who recently returned from Qom, said: "Due to the special religious nature of Qom, with religious tourists coming from inside and outside Iran, the virus spread rapidly across the country."

He said during his visit he had seen a "genuine effort" to increase operations in testing labs and hospitals in Qom and the capital Tehran.

The city's shrines have now been closed.

People gather outside the closed doors of the Fatima shrine in Iran's holy city of Qom

Did the government downplay the outbreak?

February saw two major events for the country - the 41st anniversary of the Islamic Revolution and the parliamentary elections.

"The first days that my colleagues and I recorded an abnormal respiratory disease were days before the Islamic Revolution victory day on 11 February," recalls one senior doctor, who says he sent multiple reports from his hospital to senior health ministers in Tehran warning of the outbreak.

"We believe that health officials decided to hide the fact that coronavirus had reached Iran to have their usual state-sponsored gatherings."

Iran marks the Islamic Revolution anniversary in Azadi (Freedom) square

Both the anniversary event and the elections were seen as a test of the government's popularity, after six months of chaos endured by Iranians.

These included violent protests in November following a fuel price hike, and rising tensions with the US, after Iran attacked a base in Iraq housing American troops in retaliation for the killing of the top Iranian commander Qasem Soleimani.

The downing of a Ukrainian plane that led to the death of all 176 people on board dented public trust after officials initially denied the plane had been hit by a missile.

Iran marks the Islamic Revolution anniversary in Azadi (Freedom) square

Shortly after the election, Iran's Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei accused Iran's "enemies" of exaggerating the threat of coronavirus to keep voters away from the polls.

"Negative propaganda was launched several months ago, and in the last two days their media has used every opportunity to discourage people from casting their vote on the pretext of an illness and virus," said Mr Khamenei.

More recently, Iran's health minister Saeed Namaki, rejected all claims of delaying reports, with state TV announcing "the issue was immediately announced [19 Feb] despite the fact the election was was due to be held that Friday [21 Feb]".

Iranians cast their ballot at a polling station in Shah Abdol-Azim Shrine,

Five days after the election, the number of cases confirmed by the government had risen to 139 with 19 dead.

The same day, Ahmad Amirabadi Farahani, a hardline MP from Qom, stood up in parliament and said 50 people had died in his city over a two-week period.

Deputy health minister Iraj Harirchi denied Mr Farahani's claim, and said he would resign if the death toll stood at even half that number.

Later that day, Harirchi was seen sweating profusely and coughing during a press conference on coronavirus. He later announced he had tested positive, becoming the first of many high-profile Iranian politicians to become infected.

Harirchi reportedly has since made a "full recovery" appearing live on television on 13 March.

Deputy Health Minister Iraj Harirchi wipes his sweat during a press conference

Numerous experts and journalists have suggested the official figures are a dangerous and vast underestimate of the true scale of the crisis in Iran, including a BBC Persian investigation which established on a single day, the death toll to be six times higher than reported.

But as even the official figures continue to soar, the question now for Iranians is how to stop the virus.

Living in lockdown

Alireza's father passed away in mid-March.

"Nobody in our family was there when they buried my father. I didn't even get to see his body. They just told us he'd died and had been buried in a special zone in Tehran's main cemetery."

For safety, Alireza's name has been changed.

Alireza's family were told by the authorities not to gather for a funeral but that they would be able to visit the grave once her father had been buried.

But upon arriving at the cemetery, she was told by staff it wasn't safe to enter because they were still burying so many other bodies.

"We talk more about the burial of my father than his death," she says. "I'm not a religious, or even spiritual person, but I still have this strange feeling inside, as if we disrespected my father."

The Iranian authorities have now banned all large funeral gatherings.

Several clerics, including the Supreme Leader, have also issued religious fatwas against the traditional washing of dead bodies, to protect those working as "mordeshoors" - or body-washers.

Firefighters disinfect the Tajrish Bazaar, Tehran, Iran

As the WHO calls for international "urgent and aggressive action", Iran's response continues to fall short of the measures implemented in countries such as China or Italy.

Schools, universities and seminaries have been closed, football matches cancelled, and a large-scale disinfection campaign has begun in the capital city, Tehran. All Iranians have been advised against travel and told to stay at home. And for the first time since the establishment of the Islamic Republic in 1979, Friday prayers have been cancelled.

In an attempt to prevent the spread of the disease in overcrowded jails, 155,000 prisoners were also temporarily released. This includes political prisoners, many of whom are believed to be in poor health, among them British-Iranian charity worker Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe.

However, most government buildings, offices and banks remain open.

A prevention campaign poster in the capital Tehran

Even for middle-class Iranians such as retired teachers Fatemeh and her husband - not their real names - say the problem is most people are still reliant on cash for buying everything from groceries to fuel.

'We have to go to the bank to collect our monthly pension. We are expecting to receive the Nowruz [Persian new year] special allowance in the coming days.''

Many medical experts inside and outside Iran say unless the government establishes transparent incident figures and moves to quarantine whole cities such as Qom, the virus will continue to cripple the entire country.

President Rouhani has repeatedly said the government will not place cities under lockdown and for "all shops to remain open and everyone to continue doing business", a decision many believe is simply because Iran cannot afford to do otherwise. The US sanctions have devastated the economy.

Persian new year is the country's biggest annual festival. Ayatollah Khamenei used the event to praise the country's "dazzling" sacrifices in responding to the outbreak.

For Fatemeh, it has never seemed less of a moment to celebrate.

"In all my life, I don't ever remember staying home alone for Nowruz. Even during the war, when Saddam started attacking cities with missiles, we would visit each other during Nowruz."

Tehran, Iran