Coronavirus: Lebanon's woes worsen as country pushed to the brink

- Published

Lebanon has been rocked by anti-government protests for months

For the past two months, Khaldoon Rifaa has not been able to work as a driver because of Lebanon's lockdown.

He is now back on the road, operating a minivan along the coastal motorway from his home city of Tripoli to the capital, Beirut.

But standing on the street, he is struggling to find any paying customers to fill up his vehicle.

"Before my life was good," says the father-of-five. "I'd work and I could feed my children."

"But now, there's no work - there's nothing. I don't even have the money to buy washing powder."

Khaldoon says he has racked up debts of $2,000 (£1,640; €1,840) to provide for his family and even then is four months behind on the rent.

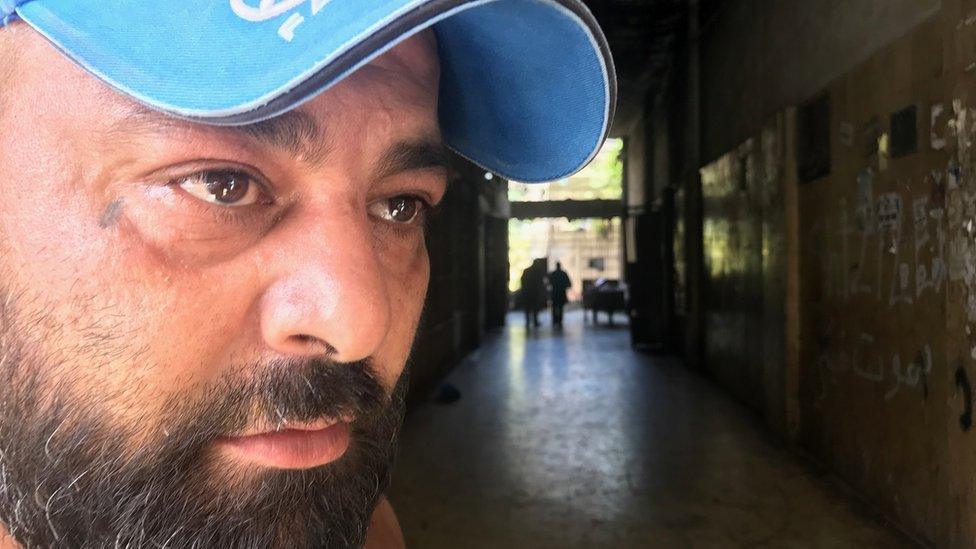

Like many Lebanese, Khaldoon Rifaa is suffering due to the country's multiple crises

Like many others in Lebanon, he has suddenly been plunged into poverty in a country that has hit breaking point.

Some are warning that the scale of the catastrophe may be more devastating than the 15-year civil war, external, which raged from 1975 to 1990.

Soaring costs

Even before coronavirus hit, Lebanon was experiencing the worst economic crisis in the country's history, which triggered large anti-government protests late last year.

While the authorities have been praised for their response to the virus, almost half the country's six million people are now living below the poverty line.

Lebanon crisis: 'The country needs our energy'

Lebanon's currency has lost nearly 60% of its value against the dollar, and, in a country that relies on imports, that has led to rampant inflation.

Hundreds, if not thousands of businesses, have gone bust, and more than a third of the population is unemployed.

The country's new Prime Minister, Hassan Diab, has warned of a "food crisis", external, saying that many people will soon be unable to afford bread.

'Really, really bad'

Nowhere is the desperation more acute than in Tripoli, the country's poorest city, which has long been neglected - and blighted by extremism in the past.

Last month, protesters torched a string of banks there. The banking system here is seen as complicit in what many Lebanese regard as the plunder of the country by their own political elite.

Lebanon has had to grapple with coronavirus alongside economic turmoil

In the city, most workers depend on their daily income, and 60% make less than $1 a day.

There are no elaborate bailouts to prop up businesses and furlough schemes to keep workers tied to their jobs - instead, people are left largely to fend for themselves.

Some are relying on food hand-outs from charities.

"Unless we help them, they'll have nothing," says Farah Ahdab, the CEO of a local charity, Izdihar, which is delivering bread to hundreds of poor families in the city.

"They may be encouraged to steal. The situation is really, really bad."

'Like dogs'

The Lebanese government is now in talks with the International Monetary Fund (IMF), but any bailout is expected to involve painful economic reforms - in a country built on a sectarian political system that is likely to face stiff resistance from the entrenched parties.

It is feared even bread might become unaffordable

"Lebanon doesn't have a future because of the country's politicians," says one man in Tripoli's main shopping district, where there was no social distancing going on and only a handful of people are wearing masks.

"The politicians treat the people like dogs. If you make a dog hungry, they will follow you to eat."

Many Lebanese fear that poverty will end up killing far more people than coronavirus.

As the country begins to lift its lockdown, the hunger and despair are growing - and protesters are once again expected to vent their anger on the streets.

The fear is that social unrest could unravel Lebanon's relative stability since the end of its civil war 30 years ago.

- Published13 May 2020

- Published4 May 2020

- Published5 March 2020

- Published13 December 2019

- Published7 November 2019