Israel annexation: New border plans leave Palestinians in despair

- Published

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu says settlements - on land claimed by Palestinians - will become part of Israel

Israel's Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu could annex parts of the occupied West Bank this summer. He says the move, stemming from US President Donald Trump's peace plan, will write another "glorious chapter in the history of Zionism".

The Palestinians are defiant. They say they are pulling out of previous agreements, risking their own fragile governing authority. To them, the move means the loss of vital land for a future state and a death blow to dreams of self-determination.

Much of the global community looks on with growing concern over what they see as a clear violation of international law, while warnings echo of a "hot summer" of boiling tensions.

How is the groundwork being laid ahead of what is potentially one of the most significant policy moves in the region in years?

'Do it right!'

My journey starts along the main highway heading south out of Jerusalem.

The road is named after Menachem Begin, the former Jewish militant leader who became Israel's sixth prime minister. He is an icon of right-wing nationalism, founding the movement that later merged to become Likud - the party now led by Benjamin Netanyahu.

The highway ramp dips past a 12-storey building covered in a giant poster of Mr Netanyahu and President Trump. "No to a Palestinian state!" it proclaims in Hebrew. "Sovereignty - do it right!"

It's a message for, not by, the current Israeli and US leaders. It's from a group of mayors of Jewish settlements in the West Bank - the territory they see as their Biblical heartland.

Settlers say a Palestinian state in the West Bank would pose a threat

The mayors want to claim Israeli sovereignty over more than the 30% of the West Bank that is on the table from Mr Trump. With Mr Netanyahu soon able to bring proposals to his cabinet or parliament to "apply Israeli law" to parts of the territory, the mayors are giving him a headache from his political right.

It's a sign of how the argument has shifted in Israel over the years.

I drive on, leaving the Begin Highway behind, passing a military checkpoint and joining a smaller road that winds its way into the West Bank, home to up to three million Palestinians, and to almost half a million Israelis living in settlements.

'My peach is not Trump's to give'

Among grapevines and olive trees, Mohammed Yehya Ayer shows me his land.

We're on a ridge outside the Palestinian village of Irtas. Some of the West Bank's familiar colour codes are on display. Orange rooftops curve across a hilltop to the south-west - the neat suburban layout of the Israeli settlement of Efrat.

Mohammed Yehya Ayer says parts of the West Bank are "already [as good as] annexed"

Beyond its fenced-off edges the land sweeps down into an empty valley, a dusty gulf of burnt ochre and rocks, before the habitation picks up again - the grey concrete blocks of Dheisheh, a sprawling urban refugee camp on the edge of the Palestinian city of Bethlehem.

Two separated worlds, side by side.

I ask Mohammed what he thinks of Mr Netanyahu's recent statements.

"It doesn't mean anything," he tells me. "These areas are already [as good as] annexed... It's all in their hands."

Mohammed goes on to explain his view.

His family farmed the land here for generations. After Efrat settlement was established in the 1980s, things began to change. He describes a frequent struggle over control.

"If I put 10 bricks here [to build a structure], the Israeli authorities come and demolish them," he says.

"Israelis... make suggestions and seize more lands on the pretext they are state land... and the government helps the settlers."

Israel is planning a new settlement, called Givat Eitam, north-east of where I walk with Mohammed. It would be considered a neighbourhood of Efrat. Mohammed's land is within an area sandwiched between the two settlements.

"If Efrat builds there by force, they might install gates and fences and not allow us to cross our lands," he says. "They would tell us to get special permits and approvals."

The Israeli authorities routinely point out that fence routes can be challenged in the planning process or the courts. They declined to comment on the specific claim about access if Givat Eitam goes ahead.

Judges are due to rule on an appeal against the land allocation for the settlement itself.

I put it to Mohammed that the Trump plan envisages the Palestinians having a state on 70% of the West Bank and a freeze on settlement expansion for four years in places outside of Israeli-annexed areas.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

He handles a freshly picked peach.

"Who is Trump to promise anything? Is this property owned by him?" he asks holding up his fruit. "I can give this peach to you because I own it. But if I don't have it, how could I offer it to you?"

'They say God is on our side and we can do what we want'

It's not far to Efrat. But the journey shows the West Bank's sharp contrasts.

Efrat is one of more than 130 Israeli settlements in the occupied West Bank

Before a watchtower, concrete stumps alongside a dust road mark out a future line to extend Israel's network of walls, fences and checkpoints - the separation barrier.

Its construction began during the second Palestinian intifada, or uprising, of 2000-2005, when suicide bombings frequently killed Israelis and Israel launched sweeping incursions into West Bank cities.

Israel says the barrier saves lives. Critics call it a device to grab land.

The settlements are seen as illegal under international law, stemming from the prohibition on countries transferring part of their populations to areas under military occupation. Israel rejects this, arguing the territory is "disputed" rather than occupied.

An armed guard waves me past a checkpoint into Efrat's quiet streets.

The Trump plan is a big break from previous peace proposals. Some speculate that these could have led to Israel formally gaining the big settlement blocs - including the bloc containing Efrat, for example - as part of a negotiated deal with the Palestinians, who want the West Bank as part of their future state.

Palestinian President Abbas says Mr Trump's "conspiracy deal won't pass"

Most of the big settlement blocs are just across the Green Line, the armistice line from before the 1967 Arab-Israeli war, when Israel captured the West Bank from Jordanian control.

But President Trump's plan potentially awards American recognition to Israel for all the settlements and the strategically vital Jordan Valley - before any negotiations with the Palestinians.

Outside a waffle bar, I chat to Yedidia Mosawi and Sharon Barazani, both in their 20s.

Yedidia tells me he works in security and comes from a settlement further south, near Hebron.

"It's an amazing place, very important for Israel," he says of the West Bank - or the Hebrew Biblical name of Judea and Samaria, as many Israelis refer to it.

Sharon Barazani and Yedidia Mosawi

I ask about Mr Netanyahu's plans. He suggests it's not enough.

"[We should] apply Israeli law to all of this land. It's ours in history. For the Jewish people it's the most important - we don't have another country to go to."

Sharon adds: "You can't tell people to go from their land, their home."

I arrive at the mayor's office. Outside is a picture of a floor mosaic found in Jordan in the 1880s.

It is known as the Madaba map, a portrayal of the Holy Land in the 6th Century. One of its Greek inscriptions, next to Bethlehem, references the Biblical location of Ephratah.

The Israeli settlement of Efrat was established in 1983. Mayor Oded Revivi is well aware of the religious and ideological connections to the land, although he says it is not the main driving force for most settlers.

Many, as he did in the 1990s, come for potentially cheaper homes in a ready formed Jewish community.

Mayor Oded Revivi says the Trump plan is a genuine attempt to solve the conflict

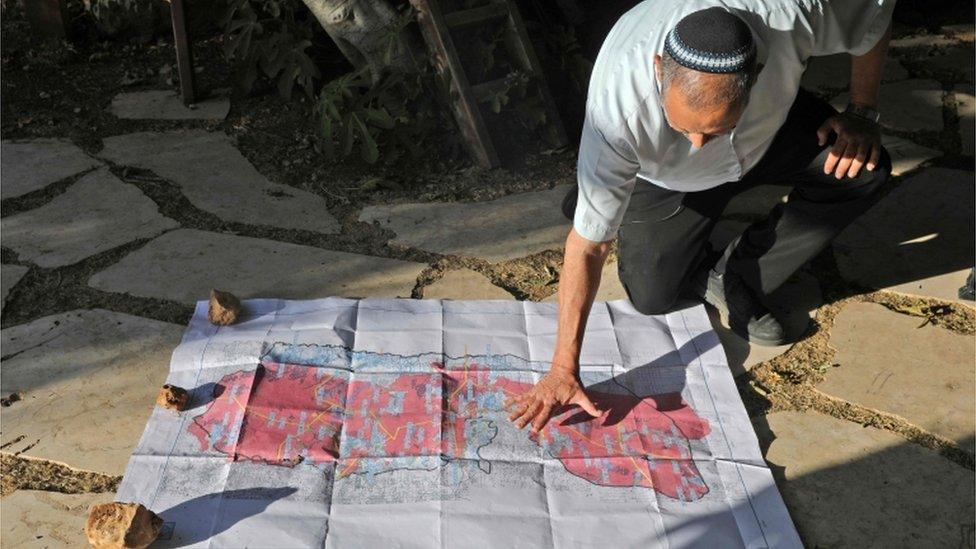

Mr Revivi talks to Mr Netanyahu. He knows members of the American-Israeli mapping team charged with working out the territorial boundaries of annexation, and he backed the Trump plan from the start.

"I thought it was a genuine attempt to try and think of another way to solve the conflict," he says.

What of his fellow mayors attacking the prime minister from the right, claiming Israeli rights to even more of the West Bank? Mr Revivi jabs at some of his colleagues politely.

"Such an attitude derives from not quite understanding the global village we live in," he says, referring to the strong counter-views of much of the outside world to any annexation.

"That we can think we are strong and mighty, and that God is on our side, and we can do whatever we want."

You need to understand the Trump deal in stages, he says. "This is stage one."

A building boom

Opponents see the Trump plan as nothing more than a way to formalise a de-facto reality developed on the ground for half a century in breach of international law.

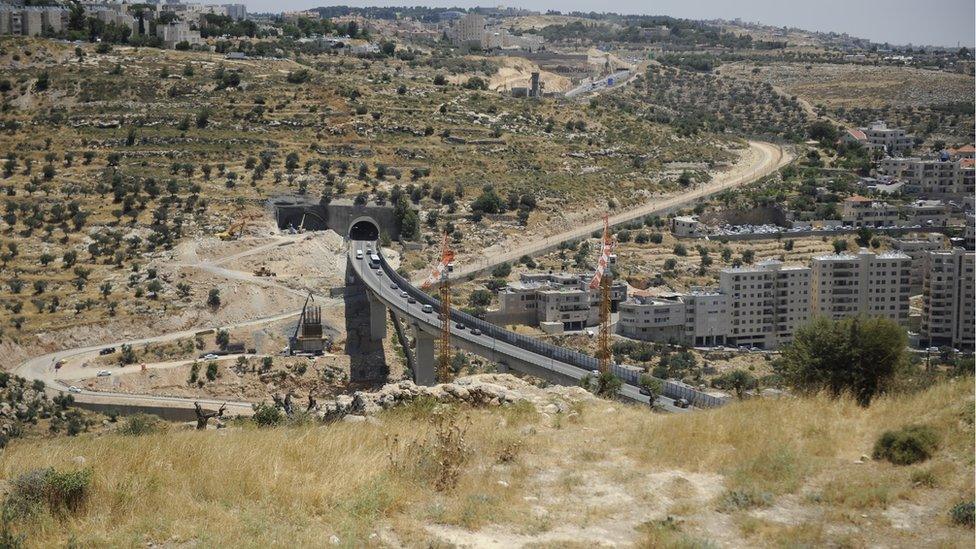

I arrive in the shadow of a huge bridge being constructed - a doubling of the road running from the Begin Highway that forges its way into the West Bank, connecting Jerusalem to Efrat and the other settlements further south.

A bridge under construction will make it easier to travel between Jerusalem and the settlements

We stand a few metres from a section of the separation barrier - an 8m-high (26ft) concrete wall here that conceals from our view Palestinian homes on the other side, as cars bearing Israeli number plates zoom across the bridge above us.

This is the "whole story of the West Bank in the last 53 years", according to Dror Etkes, who runs the Israeli non-governmental organisation Kerem Navot (Navot's Vineyard - named after a Biblical figure murdered for his land), which monitors settlement construction.

"It's about taking from the Palestinians and giving to the Israelis. The way you do it is confiscating land and allocating only to Israelis. That's one. And the other is sealing up and preventing the expansion of Palestinian communities," he says.

We watch Eastern European workers carry huge steel beams.

Infrastructure projects anticipate a growth in population in areas eyed for annexation

Mr Etkes says this is the biggest boom in infrastructure projects carried out by Israel in the West Bank in two decades.

More roads, water pipelines and sewage purification systems are being built, he says, to allow for significant future growth in settler numbers.

'Palestinian citizens of a future Palestinian state'

Mr Etkes and other monitoring groups warn that annexation could leave people like Mohammed Ayer in territorial enclaves.

A study by the US think tank the Washington Institute, external suggests "full annexation" by Israel of up to 30% of the West Bank could affect almost 110,000 Palestinians.

Mr Netanyahu has said those in the Jordan Valley, for example, would remain "Palestinian subjects". Critics fear that means they would effectively live in islands of only Palestinian civil control, surrounded by land under full Israeli jurisdiction.

Palestinian villages and Jewish settlement sit side by side in some areas

The Palestinian leadership, along with almost 50 experts appointed by the United Nations Human Rights Council, say this would formalise a system of "apartheid" in the West Bank - two peoples ruled by one state in the same space with unequal rights.

Some Israeli opposition figures from Jewish majority parties view the plan as a nightmare, being carried out carelessly. They see little gain from unilateral annexation, while leaving Israel's global image tarnished.

But retired Israeli Brigadier-General Yossi Kuperwasser believes the numbers of Palestinians caught in any unilateral application of sovereignty would be "negligible".

He says many could receive Israeli residency in the interim and suggests the Palestinian leadership should engage with the Trump administration.

"This was the logic of the US peace plan," he says. "The Palestinians are going to be citizens of the future Palestinian state."

'We are not going to throw away the key and go home'

The drive to the Palestinian city of Ramallah is often complicated. The city has a small number of entry and exit points, and big traffic jams are a constant feature.

Ramallah is home to the headquarters of the Palestinian Authority (PA).

The governing body was born as a result of the Oslo Accords of the 1990s - the high-water mark of Israeli-Palestinian peace-making.

Now, in a bid to increase international pressure to avert annexation, Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas says the PA is no longer bound by agreements with Israel and the US, including on security.

Israel and the Palestinians signed a peace accord in 1993 but a final treaty is still to be reached

Some fear suspending such co-ordination, if fully delivered, could precipitate a collapse of the PA and the potential for a slide into chaos in the West Bank.

Amid the bitter divisions of Palestinian politics, the militant group Hamas - the main rival of President Abbas' Fatah movement - could try to capitalise and is warning of a confrontation with Israel.

I arrive for a news conference by the Palestinian Prime Minister, Mohammad Shtayyeh. Security is always tight. Now there's also an anti-coronavirus washdown before you enter the building - I step into a booth where I'm showered with sanitiser fluid, mostly soaking my hair.

The pandemic is slowing entry to the building, but it has not paused the region's politics.

Mr Shtayyeh believes Israel's plans bring the conflict to a new junction in history.

"This peace process has reached a serious impasse," he says. "We are facing a moment of truth for us as a Palestinian leadership."

I ask about the prospects for the future of the PA.

"Let's not fool ourselves," he replies. "The PA is not a gift from anybody. It came into being because of the Palestinian people... We are not going to throw away the key and go home."

Mr Shtayyeh accuses the international community of failing to act.

Why doesn't his leadership engage with the US and negotiate, he is asked.

He says annexation would amount to the "destruction" of a future Palestinian state, and suggests accepting it would leave the PA becoming "a bunch of traitors - and we will not be".

'Walking a tightrope'

What happens next? Mr Netanyahu continues to talk up his plans, despite speculation that they were a gimmick to rally the right wing in three deadlocked elections.

"These territories are where the Jewish nation was born and grew," the prime minister said of the settlements when his new coalition government was about to be sworn in in May.

"[Applying Israeli law to them] won't distance us from peace. It will bring us closer."

Annexation will redraw Israel's eastern frontiers

The coalition agreement allows him to bring proposals to the cabinet or the Israeli parliament from 1 July.

The US administration, having signalled in May that it didn't expect the process to be rushed, may now be ready to back the proposals Mr Netanyahu arrives at broadly on the conditions that he commits to the Trump plan as a package (meaning keeping open the possibility of Palestinian negotiations in the next four years) and that there is consensus among the principle players in the coalition.

This adds to the significance of the views of Benny Gantz, the defence minister and alternate prime minister due to take over from Mr Netanyahu late next year.

Mr Gantz is thought to be less willing to back sweeping unilateral annexation plans and he wants co-ordination with Washington and Arab countries that have ties with Israel.

The latter - in particular neighbouring Jordan - have voiced vehement opposition to any form of annexation, raising concerns about regional stability if the move goes ahead.

Mr Gantz's Blue and White party, whose success in the elections was partly down to left-wing votes, is "walking a tight-rope" on the issue says Lahav Harkov, diplomatic correspondent at the Jerusalem Post.

While Mr Netanyahu "wants to push for all of it", Mr Gantz and Foreign Minister Gabi Ashkenazi, his Blue and White party colleague, are a lot more reticent, she tells me.

More meetings between these key players seem certain.

I make another return to Begin Highway, this time heading back into Jerusalem. The Israeli prime minister's office and the parliament are off a junction heading east. More history-making could lie on the road ahead.

.

- Published25 June 2020

- Published29 January 2020

- Published28 January 2020

- Published29 January 2020

- Published28 January 2020

- Published21 November 2024