Kylie Moore-Gilbert: Australia says lecturer jailed in Iran 'is well'

- Published

Kylie Moore-Gilbert, a lecturer at Melbourne University, has been in jail since September 2018

Australia's ambassador to Iran has visited a British-Australian academic serving a 10-year sentence for espionage and found that she is "well".

Kylie Moore-Gilbert, a lecturer at Melbourne University, has been detained in Iran since September 2018.

She was tried in secret and strongly denies all the charges against her.

Concerns for her wellbeing escalated last week when news emerged that she had been transferred to Qarchak, a notorious prison in the desert.

The jail is sometimes used as punishment for Iranian political prisoners and conditions have been described by former inmates as abysmal.

But in a statement, Australia's Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) said Ambassador Lyndall Sachs had been granted access to Ms Moore-Gilbert on Sunday and found her to be well.

She "has access to food, medical facilities and books", the statement said, adding that Australia would continue to seek "regular consular access".

"We believe that the best chance of resolving Dr Moore-Gilbert's case lies through the diplomatic path," it said.

Ms Moore-Gilbert's family said they were "reassured" by the ambassador's visit.

"We remain committed to getting our Kylie home as soon as possible and this is our top and only priority," they added.

What is Ms Moore-Gilbert's situation?

The Cambridge-educated academic was travelling on an Australian passport when she was detained at Tehran airport in 2018 as she tried to leave following a conference.

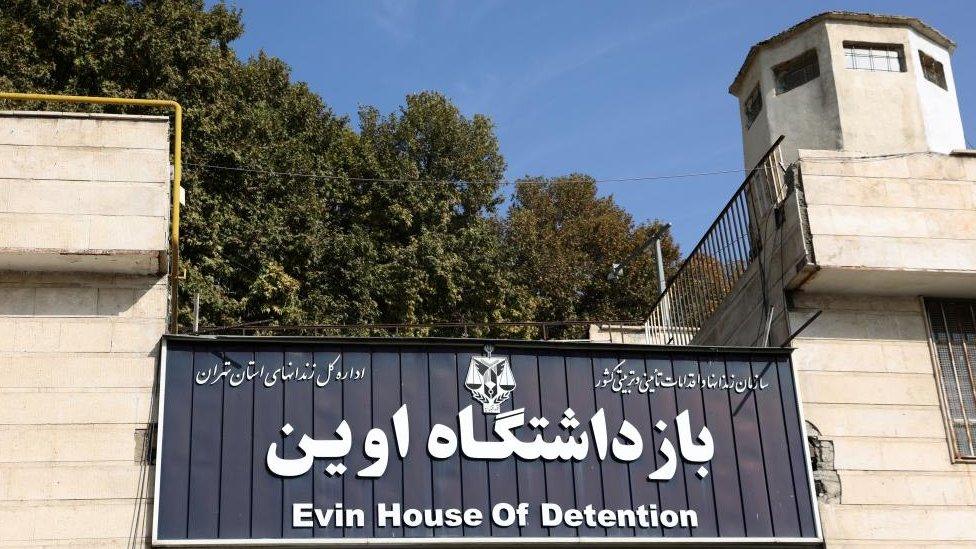

Before being moved to Qarchak prison, she had spent almost two years sleeping on the floor of a cell at Evin prison in the capital, Tehran, according to a friend.

She has been in solitary confinement and on several hunger strikes, and she is said to have been beaten for trying to comfort new prisoners by passing notes and writing to them on prison walls.

In letters smuggled out of Evin prison in January, the lecturer said she had "never been a spy" and feared for her mental health. She said she had rejected an offer from Iran to become a spy.

"I am not a spy. I have never been a spy, and I have no interest to work for a spying organisation in any country," she wrote.

You might be interested in watching:

Why one mother's personal plight is part of a complicated history between Iran and the UK (video published August 2019 and last updated in October 2019)

- Published14 September 2019

- Published12 September 2019

- Published28 July 2020

- Published19 September 2023