Ahmadreza Djalali: The Swedish-Iranian doctor on Iran's death row

- Published

Ahmadreza Djalali had said that he was being held as a reprisal for refusing to spy for Iran

It was supposed to be just another regular work trip - two weeks in Tehran and then back home to Stockholm. Four years on, Vida Mehran-nia still regrets not saying what she calls a "proper goodbye" to her husband.

Ahmadreza Djalali, a doctor with expertise in emergency medicine, was sought after by the authorities in Iran where he regularly hosted seminars and gave lectures. But something made Vida phone him on his way to the airport in 2016 to wish him a safe journey.

"Even two weeks apart was too much to bear," she tells me over a cup of coffee in a central Stockholm cafe.

She cannot meet me at home as her younger son does not know his father is a prisoner in Iran. He still thinks his dad is away on a work trip.

It's four years since the doctor, who has since become a dual Swedish-Iranian national, was arrested by Iran's intelligence service.

He was later sentenced to death for, Iran says, passing on classified information to Israel's Mossad intelligence agency to help them assassinate Iranian nuclear scientists.

His lawyer said his confession was obtained by torture.

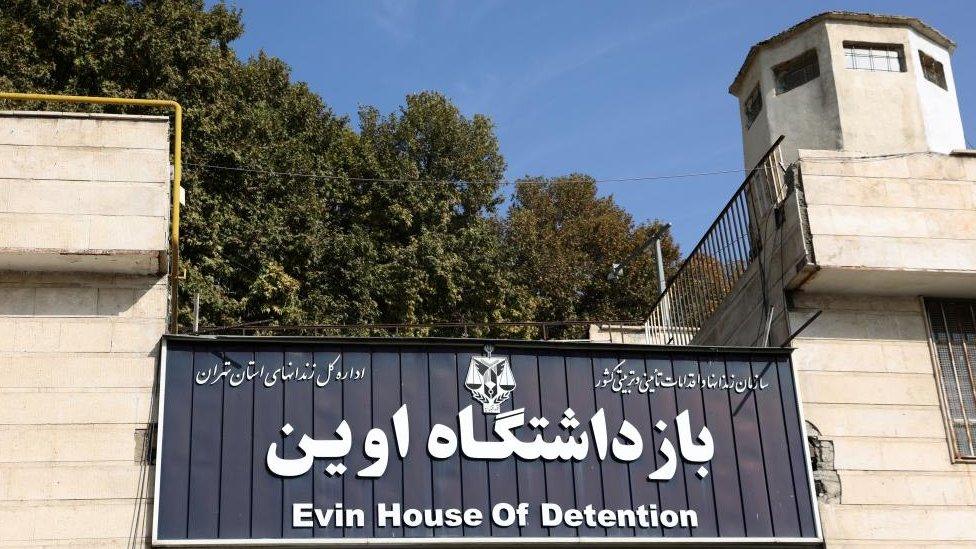

Ahmadreza Djalali is on death row in Iran

On 24 October, Ahmadreza was moved to solitary confinement in section 209 of Evin prison, one of Tehran's largest and where most political prisoners are held.

On 1 December, he had a short phone call with his family where he said he was being transferred to death row. Vida raised the alarm that the Iranian authorities were getting ready to execute her 45-year-old husband.

"He was extremely desperate and asked me to help and prevent his execution and save his life," she tells the BBC.

"He feels so feeble because he thinks he can't do anything and he has no power to save himself, stuck alone in a cell."

He then spoke to their daughter, who is 18 years old.

"She has been crying and calling all politicians and human rights activists to save her father's life," says Vida.

"It is so difficult and we are all suffering so much. Nobody can imagine what we have been through. It is like torture."

Vida Mehran-nia (left) still regrets not saying a "proper goodbye" to her husband four years ago

And the toll on the family is immense.

"My youngest son was only four when Ahmadreza went to Iran, he is now eight years old," says Vida.

"He always asks about his dad and remembers when his father put him on his shoulders and they had a lot of fun."

Ahmadreza moved to Sweden in 2009 for higher education.

His family joined him a year later after he was accepted for a PhD at Stockholm's Karolinska Institute.

They then moved to Italy where he did a postdoctoral degree and returned to Sweden in 2015.

Ahmadreza lectured on how to make hospitals and regions disaster-proof

The family had a simple life until Ahmadreza's fateful trip to Iran.

In 2018, Sweden gave Ahmadreza citizenship while he was in prison. Some in Iran said this proved he has been "an asset to the west".

His wife rejects this and says they already had a permanent resident permit after Ahmadreza completed his PhD.

He was a respected scientist in Sweden who researched how to make hospitals and regions disaster-proof.

His photo is still on the notice board at the Södersjukhuset hospital where a branch of Karolinska institute is based, beside the title of his PhD thesis: Preparedness and Safe Hospitals: Medical Response to Disasters.

He kept in touch with his PhD supervisor, Professor Lisa Kurland.

They were supposed to have a research meeting in April 2017, but he never turned up.

Professor Lisa Kurland says Ahmadreza reassured her his visits to Iran were safe

"For him not to be there and not to show was completely out of character and just that made me wonder [whether] something had happened," says Lisa Kurland, Professor of Emergency Medicine at the Karolinska Institute.

"I actually did ask him pretty much before and after every visit if it was safe for him and he said it was."

When Ahmadreza was arrested in Iran, his family initially told friends and fellow researchers that he was involved in a car accident and was in hospital there.

They thought this would help get him released, but to no avail. Then they decided to go public.

Lisa says it was an "unimaginable shock" when she heard he had been sentenced to death.

"I remember his passion that he wanted to make a difference," she says.

"He wanted to use scientific tools and methodology to get a PhD but also through these scientific tools, help the people in Iran."

Ahmadreza's friends and colleagues have shared photos with me showing him giving seminars across Europe and in Iran.

Katarina Bohm and Veronica Lindström, both associate professors at the Karolinska Institute, shared desks with Ahmadreza.

They describe him as a "polite, humble and decent person" who always talked about Iran and how he wanted to visit universities there "to share his knowledge and help people" despite the political situation.

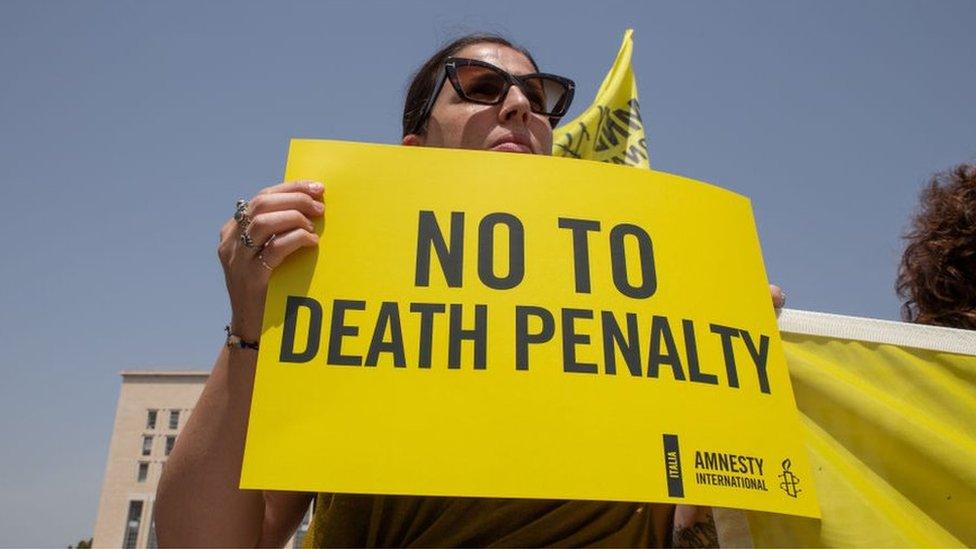

Amnesty International has urged Iran not to carry out the "appalling" sentence

In 2017, 75 Nobel prize winners wrote an open letter to the Iranian authorities asking for Ahmadreza's immediate release.

Two weeks ago, 150 Nobel Laurates send another letter to Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, asking him to intervene and release the doctor.

Last month, Amnesty International asked Iran to halt his execution. The Swedish foreign minister has also spoken to her Iranian counterpart and asked for the death sentence to be halted.

However, Iran rejected Sweden's appeal and warned against "all interference".

The list of foreign nationals and dual citizens Iran has detained for spying is long. Human rights groups accuse Tehran of using them as pawns to gain concessions from foreign governments.

Just last month, Iran released a British Australian lecturer serving a 10-year sentence for spying in exchange for three Iranian prisoners.

Ahmedreza dedicated his PhD thesis to the people of Iran, writing on the first page: "To the people killed or affected by disasters around the world especially the people of the Bam city in Iran."

In 2003, an earthquake in Bam killed at least 26,271 people.

He never thought his degree in emergency medicine could lead to death row. His wife says all he ever wanted to do was save lives and prevent the repeat of such disasters.

Ahmadreza's daughter has followed in her father's footsteps and is now enrolled at the same university where her father defended his PhD.

It's bittersweet for Vida, who has supported her daughter amid the huge absence in their lives.

"When she finished high school with top scores her father wasn't with her to celebrate," Vida says through tears.

"When she got accepted at the Karolinska institute and like her father she chose medicine again, her father wasn't there."

You may also be interested in:

Love Child follows a 'secret' family as they flee Iran, after an illegal affair

Related topics

- Published25 November 2020

- Published17 December 2017

- Published19 September 2023

- Published10 April 2019

- Published25 January 2024