The Instagrammers who worry Iran

- Published

Human rights activists say Instagramer Fatemeh Khishvand has been made an example of by Iran

Growing up in Iran, Fatemeh Khishvand dreamed of becoming famous, posting selfies on Instagram in the hope of getting noticed.

Typical enough - only Ms Khishvand's selfies were anything but.

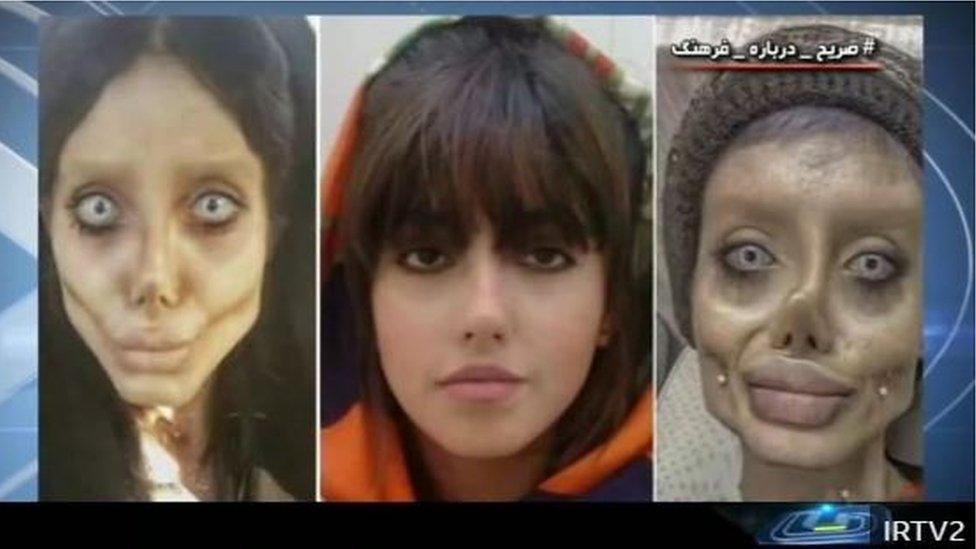

They were heavily doctored photos in which her face appeared gaunt, distorted, and enhanced by make-up.

Posted under a pseudonym, Sahar Tabar, the photos were so striking they attracted international media attention when they first appeared in 2017.

In some, Ms Khishvand bore an uncanny resemblance to American actress Angelina Jolie. This led to false rumours that the teen had undergone 50 cosmetic surgeries to look like the Hollywood star but, as she would later clarify, the Corpse Bride character from Tim Burton's titular musical fantasy was her true inspiration.

Soon, her alter ego had almost 500,000 followers on Instagram, earning her the fame she had always desired.

But that fame came at a price.

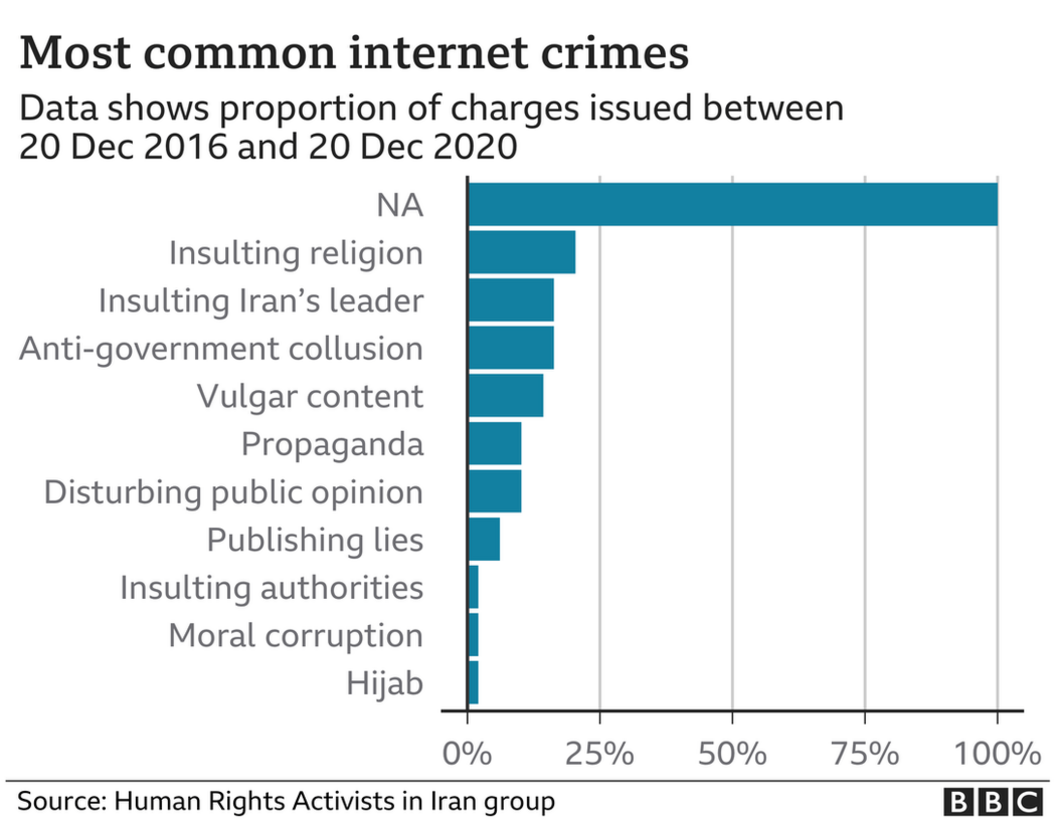

In Iran, it can be dangerous to post on social media. The country's Shia Muslim authorities enforce strict laws about what can and cannot be posted. To them, Ms Khishvand's photos were seen as crimes, not the clever Photoshop trickery of a teenage girl.

So, in October 2019, Ms Khishvand was arrested on a raft of charges, including blasphemy, instigating violence, insulting the Islamic dress code and encouraging corruption among young people.

Her Instagram account was deleted and for more than a year she languished in jail, detained without bail. Eventually an Islamic Revolutionary Court - known for their secrecy and politically motivated rulings against dissidents - delivered a sentence of 10 years in prison in December last year.

Ms Khishvand came to attention for her resemblance to a "zombie" version of Angelina Jolie

The severity of the punishment was met with shock and condemnation.

"The Islamic Republic has a history of arresting women for dancing, for singing, for removing their compulsory veiling, for entering a stadium, for modelling, but come on - this time, for just using Photoshop," Masih Alinejad, a prominent Iranian journalist and activist, said in a Twitter video.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

As Ms Alinejad's reaction suggested, Ms Khishvand's case is considered a new extreme in Iran's draconian treatment of social media users.

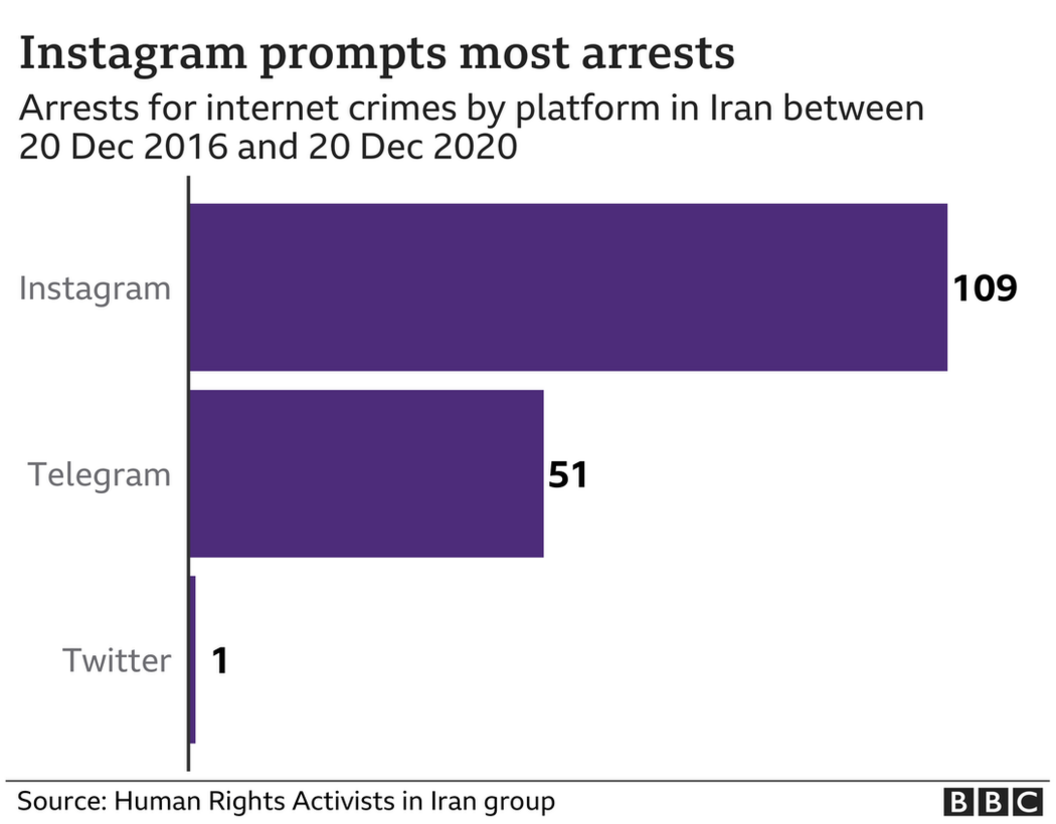

Precise data on internet crimes in Iran is hard to come by. But, according to research by the US-based Human Rights Activists in Iran group, at least 332 people have been arrested for their internet activities since 20 December 2016. Of those, 109 were for activities on Instagram, the group said.

As the only major social media network not blocked by the government, Instagram is a popular platform for young Iranians to express themselves.

This has created a dilemma for the government, which experts say is loath to block the tool for fear of provoking unrest, hampering business owners who rely on it for advertising, and severing a useful means of communication with its citizens. Instead, the government has attempted to act as a moderator.

More on Iran's censorship of social media:

Iranian Parkour athlete Alireza Japalaghy was arrested over a rooftop kiss

"For so long, Iran has tried to police culture unsuccessfully," Tara Sepehri Far, an Iran researcher for Human Rights Watch (HRW), told the BBC.

"There have been several waves of Instagram influencers being called in and interrogated."

One wave included six Iranians who, in 2014, were given suspended jail sentences and lashes for appearing in a video dancing to Pharrell Williams's song Happy. Another came in 2018, when a teenage gymnast was arrested for posting videos of herself dancing to pop music.

Each followed a similar pattern. Instagram personalities were harassed, arrested and prosecuted by Iranian authorities, which activists say pressured them to "confess" their alleged crimes, sometimes on state TV.

Indeed, that's apparently what happened to Ms Khishvand, who was paraded on Iranian Channel Two (IRTV2) as "zombie Angelina Jolie" a few weeks after her arrest.

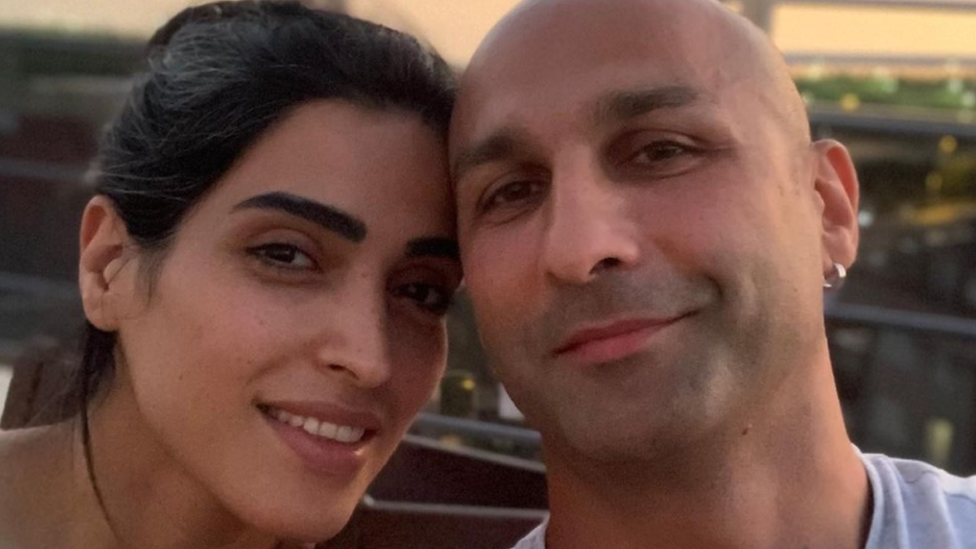

Seyed Ahmad Moinshirazi, 42, says he and his wife Shabnam Shahrokhi, 38, are familiar with the repressive methods of Iranian authorities. They too were popular social media influencers whose Instagram accounts fell foul of the law.

Mr Moinshirazi said that, from 2018, he was subjected to a campaign of intimidation by Iran's Cyber Police, which summoned him for questioning and demanded a signed pledge of co-operation.

During one hours-long interrogation, Mr Moinshirazi said he was repeatedly threatened with baseless espionage charges and ordered to purge his account of certain posts, such as those that showed his wife without a mandatory headscarf, known as a hijab.

Shabnam Shahrokhi and Seyed Ahmad Moinshirazi have hundreds of thousands of followers on Instagram

"They said these posts had contaminated Iran with Western culture," Mr Moinshirazi, a retired kickboxer better known as Picasso Moin, told the BBC.

The posts were removed as requested, yet the harassment continued, culminating in the couple's arrest and release on bail of $200,000 (£147,000; 164,500 euros) in 2019.

"Our lawyer said they definitely want to see some blood," father-of-two Mr Moinshirazi said.

A lengthy jail term seemed certain. So, fearing for the lives of his young children, Mr Moinshirazi and his family fled to Turkey in September 2019.

The couple often shared videos of them practising kickboxing together

Prosecutors were furious, Mr Moinshirazi said. No wonder, then, that the couple were sentenced harshly in absentia, receiving 16 years in prison, 74 lashes and a fine between them.

Mr Moinshirazi believes the Iranian government wanted to make an example of him, like they did to Ms Khishvand.

"This is how Iran works," he said. "In order to distract from other things in the country, they find cases to push their agendas. And Sahar Tabar is one of them."

Tellingly, Ms Khishvand revealed her sentence in an interview with Rokna, a private news agency thought to have close ties with the Iranian government. In the interview, she said she had been convicted of two of the four charges against her, but hoped to be pardoned.

Meanwhile, more lurid articles appeared on Rokna. Written in a gossipy, stigmatising tone, the articles portrayed Ms Khishvand as the troubled child of a divorced couple, a loner whose desperation for Instagram fame was indicative of poor education, immorality, and mental illness.

A mental health condition that Ms Khishvand said she had in the interview was a prominent feature of Rokna's coverage. Prosecutors, Ms Sepehri Far said, have a habit of promoting "their own version of the story, their propaganda" through the media.

"In the case of Sahar, they brought her before the camera to talk about the history of her mental health and her troubled family life," Ms Sepehri Far said. "They're promoting this narrative of, if you're taking things to that extreme, you have a troubled family."

Iranian TV broadcast an interview with Sahar Tabar after her arrest last year

For now, Ms Khishvand has been shown some mercy. At the end of December 2020, she was granted bail while she appeals her sentence.

"This is a small reward for her TV admission under duress, dismissing the lawyers and obeying their plans," her former lawyer Saeid Dehghan said.

As for the appeal, much depends on the mood of prosecutors who did not differentiate between Ms Khishvand and the cartoonish persona she invented.

"In the end, she remains simply a teenager who is being cruelly and publicly punished and humiliated for daring to express herself outside the bounds of Iran's arbitrary rules governing personal social media use," Jasmin Ramsey, communications director for the Center for Human Rights in Iran, told the BBC.

Additional reporting by BBC Persian journalist Soroush Pakzad.

Related topics

- Published16 July 2020

- Published25 December 2019

- Published24 June 2020