Iran nuclear deal: Clock ticks as rivals square up

- Published

The nuclear deal has unravelled since the US pulled out in 2018

The window for saving the international nuclear deal with Iran is rapidly narrowing - and a power-struggle inside the Islamic republic between those for and against it could soon seal its fate.

Iran holds crucial presidential elections in June, and hardliners who see the deal as a humiliation want to stall its revival before the polls. The incumbent president, Hassan Rouhani, a relative moderate and champion of the deal, cannot stand again following two terms in office. Anti-deal conservatives - already dominant in parliament - hope to replace him with a figure of their own.

While in the US opposition to the deal can generally be split along Republican (against) and Democrat (for) lines, in Iran it involves a more complicated political dynamic. This is because of how Iranian public opinion has largely turned against the regime since US sanctions were re-imposed in 2018 after the administration of former President Donald Trump abandoned the deal.

Growing discontent

On one hand, there are the hardliners who feel that Mr Rouhani's government has been too conciliatory and that a government led by themselves can extract more concessions from the US.

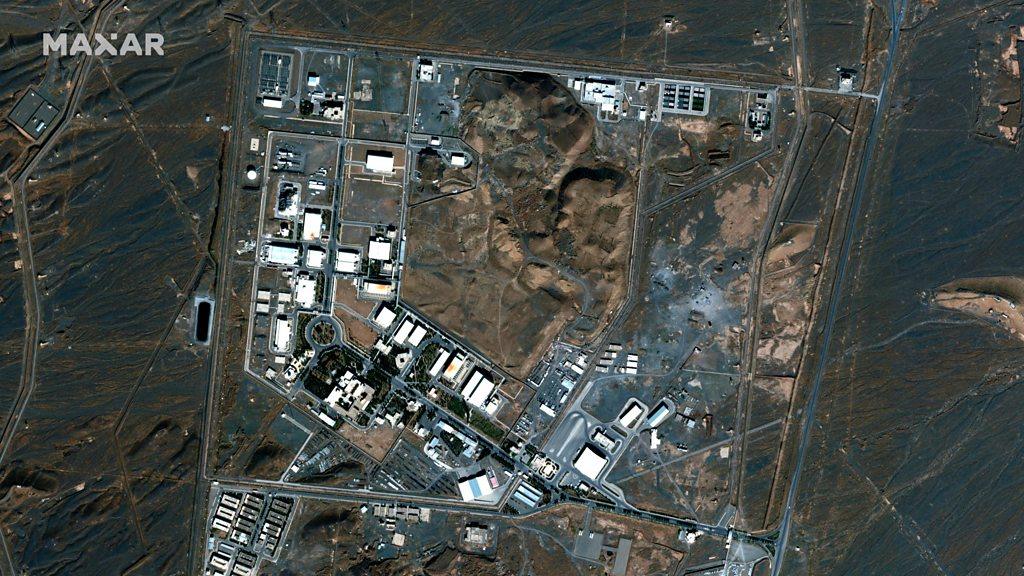

This was the strategy behind the passing of a bill in December that reduces even further Iran's nuclear commitments by setting a 22 February deadline for sanctions removal by the US or have Iran bar short-notice inspections of sites by International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) experts.

Iran has accused the US and Israel of killing one of its top nuclear scientists

President Rouhani has accused his hardline rivals of wanting to take credit for actually reviving the nuclear deal and even went as far as accusing them of "wanting Trump to have won US elections" so it would not happen on his watch.

On the other hand, many Iranians are not too excited about any measures that can give a new lease of life to a regime under siege by economic strangulation and whose legitimacy is questioned at home and abroad more than ever.

This public discontent has been fuelled by years of crippling US-led sanctions intensified under Donald Trump, which have led to inflation, rising unemployment and unprecedented anti-government street protests - which in turn led to more repression.

Iran's nuclear programme: What's been happening at its key nuclear sites?

Many frustrated and disillusioned Iranians have subscribed to the "regime change" school of thought advocated by supporters of Donald Trump's "maximum pressure" policy, though the former US administration never officially endorsed such a move.

Pro-Trump sentiments voiced around the time of the US elections by some Iranian academics, political activists and even former officials - from the daughter of ex-President Hashemi Rafsanjani to the adviser of another former President, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad - continue to be expressed on Iranian social media.

Many Iranians may feel that a revival of the nuclear deal will only prolong their hardship by extending to the regime greater international acceptance, and as a result will not bother voting in the June elections. Low turnouts in Iran historically tend to favour hardliners.

Iranian hardliners have been branded "sanction merchants" by moderates, referring to their vested economic interests in maintaining an underground economy that reaps profits by evading global trading restrictions.

Abbas Akundi, a moderate government minister, said such profits amounted to some "$25bn per annum".

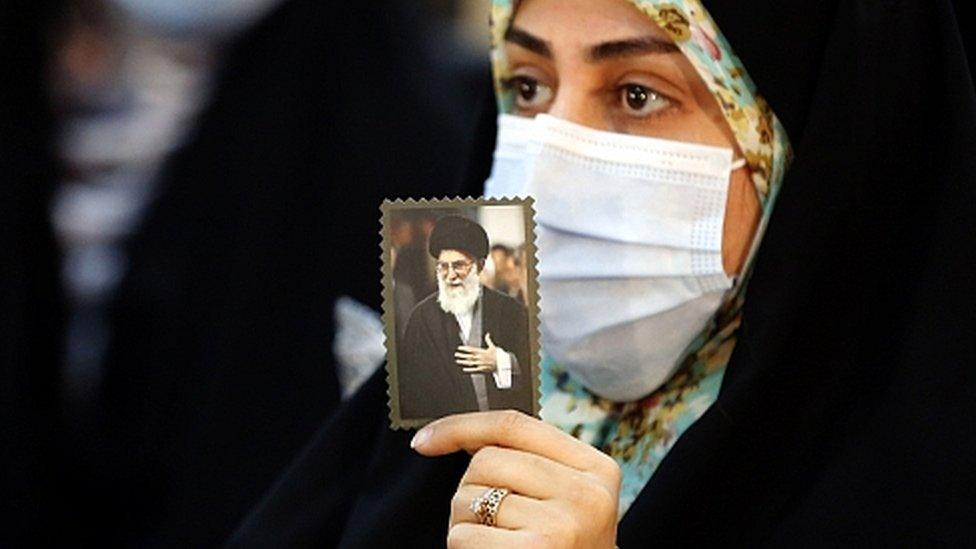

Eyes on Khamenei

Enter Iran's Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, who has the final say on important foreign policy questions.

His views are often considered as close to that of the hardliner faction in the Islamic Republic, although he went along with the agenda of the Rouhani government in striking the nuclear deal with the West. At the same time, he always kept a sceptical distance in the hope of taking credit for its success and denying responsibility for its failure.

Iran's Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei has the final say over its nuclear programme

Understanding Ayatollah Khamenei's calculus can be important in predicting what may happen in the months ahead.

Mr Rouhani needs Ayatollah Khamenei's support, which can only be forthcoming if the US is seen as making the first move.

For now the immediate problem stopping Iran and the US from going back to the nuclear deal is who initiates the process.

However, even a revived deal with all the political theatre that goes with it, may not be enough in itself to convince Iranian voters that go to the polls.

For this to happen, they may need to see immediate economic benefits, including a fall in the cost of living, especially in the price of food staples.

Hence, the repeated insistence by Iranian diplomats that "time is running out".

Related topics

- Published7 February 2021

- Published16 November 2021

- Published19 January 2021

- Published8 February 2021

- Published28 November 2020