Covid: The clarinettist who took on Lebanon's vaccine scandal

- Published

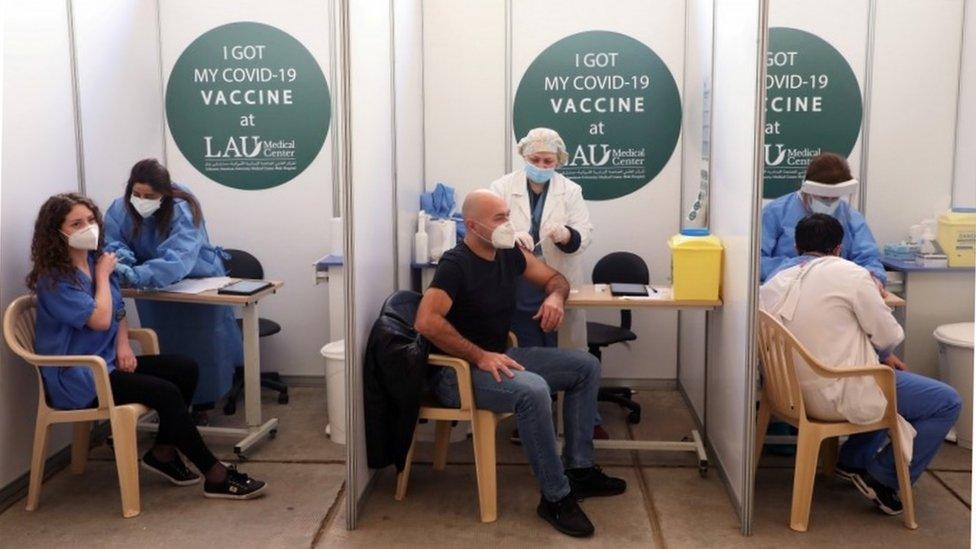

Lebanon finally began its vaccination programme last month

Eighty-year-old Joseph al-Hajj loves nothing more than playing his clarinet.

He knows you need a good set of lungs to play the wind instrument. As a professional musician, he has performed for a president, a pope and toured the world. On the wall of his home is a picture of him meeting Betty Ford, the wife of the late US President Gerald Ford.

For the past few months, Joseph has been tucked away in his mountain village of Mtein - a 45-minute drive from the capital, Beirut - shielding himself from the coronavirus pandemic. But when Joseph heard that more than a dozen of Lebanon's politicians had got the vaccination inside the country's parliament last month, he was furious.

"They told us people over 75 were the priority," he said, wearing a face mask and sitting outside on his balcony. "I have health problems, deep vein thrombosis in my legs, which affects my lungs. And for the last few months, I haven't been able to play my instrument as a precaution."

Joseph al-Hajj: 'The politicians had no right to come before us'

Even in a country used to political scandals, this was seen as a particularly shameless act.

So, Joseph - a mild-mannered man who is at pains to point out that he is not against the government - decided to sue the ministry of health, with the help of his son who is a lawyer, for a vaccination.

"The politicians had no right to come before us," he says. "This is matter of life and death."

'A lot of mistakes'

The arrival of the vaccines in early February on a private jet had been a bright spot in what has been a year and a half of relentless misery for Lebanon. The country's economy has collapsed with more than half the country now living in poverty, and then last summer a blast at the port of Beirut killed more than 200 people and destroyed large parts of the capital.

Perhaps, unsurprisingly, many Lebanese viewed the coronavirus crisis - all-consuming in Western countries - as not a priority because infections remained relatively low in the small Mediterranean nation. The Lebanese government was initially praised for its handling of the pandemic, taking measures such as closing the country's only international airport for several months to try to curb the spread of Covid-19.

But that changed over the Christmas period when big parties became super-spreader events: death rates soared and the country's hospitals were overwhelmed.

There is widespread anger against the government over its handling of a succession of crises

The fact that the World Bank - which allocated $34m (£24.5m) to fund the vaccines, enough to cover doses for about a third of the country's population - was involved in the inoculation programme led some Lebanese to be hopeful that things might be different this time around. The World Bank demanded transparency and a top official announced there would be no "wasta" - the Arabic word generally meaning nepotism - that would allow the rich and powerful to skip the queue. It did not work.

A week later news broke that a group of MPs had been vaccinated inside the parliament, provoking an outcry - a call for the World Bank to halt the programme.

"I am in direct contact with patients and I have no ability to get the vaccine right now," says Hadi Mrad, a doctor and outspoken critic of the government. "I think the World Bank should stop helping this government because it's simply a bad government that has made a lot of mistakes and has killed the population."

Lebanon ambulance driver: "Hospitals can't take our Covid patients"

Dr Mrad believes the vaccination programme should now come under the remit of university hospitals and the Red Cross/Crescent - organisations that are widely trusted in Lebanon.

Court order

Despite being furious, the World Bank, for now, anyway, is sticking with the Lebanese government. But it has warned the country's leaders not to step out of line again otherwise the Bank will pull funding for the vaccination programme. And, anecdotally at least, the rollout now appears to be working relatively smoothly since the scandal at parliament erupted.

As for Joseph, a judge ruled at the start of this month that he should be vaccinated within 48 hours.

However, it took three more weeks of uncertainty, as local officials told his family there were others ahead of him in the queue.

"I just wanted to be vaccinated," says Joseph. "I don't want to get in a fight with anyone."

Joseph finally got the jab on Tuesday - the one thing he was waiting for to start playing his clarinet again - for now, his sense of harmony restored.

Related topics

- Published5 July 2022

- Published31 January 2021

- Published25 January 2021