Israel-Gaza violence: The strength and limitations of Hamas' arsenal

- Published

Hamas and other Palestinian militant groups in Gaza have a wide variety of missiles

While death, damage and suffering have been caused to both sides in the escalating hostilities between Palestinian militant groups in the Gaza Strip and the Israeli military, this remains a hugely asymmetric struggle.

Israel is the vastly more powerful player and its air force, armed drones and intelligence-gathering systems enable it to strike targets in Gaza pretty much at will. It insists that its targeting is restricted to sites used for military purposes but the density of the Palestinian population and the fact that Hamas and Islamic Jihad facilities are located close to, and often hidden under, civilian buildings makes the avoidance of civilian casualties altogether impossible.

Hamas and Islamic Jihad, though the weaker parties, have weapons enough with which to attack Israel. They have already tried a variety of tactics. Israeli defences shot down a drone - possibly armed - that had sought to cross into Israel from Gaza. And an Israeli military spokesman said an "elite Hamas unit" had attempted to infiltrate Israel through a tunnel from the southern part of the strip. The Israeli military, it seems, had advance warning of this and, according to the spokesman, was able to "cause the tunnel to implode".

Israel says more than 1,000 rockets have been launched from Gaza since Monday night

But by far and away the most significant weaponry in the Palestinians' arsenal is their wide variety of ground-to-ground missiles. Some of these (along with other systems employed like the Kornet guided anti-tank missiles used during recent days), are believed to have been smuggled in through tunnels from Egypt's Sinai peninsula.

But by far the bulk of the Hamas and Islamic Jihad arsenals come from a dynamic and relatively sophisticated manufacturing capability inside the Gaza Strip itself. Israeli and outside experts believe that Iranian know-how and assistance have played a significant role in building up this industry. Accordingly, weapons manufacturing and storage sites have been among the chief targets of the Israeli strikes.

The Israeli military has carried out hundreds of strikes on Gaza in response to the rocket fire

Estimating the stockpile of Hamas missiles is impossible.

It certainly includes many thousands of weapons of varying ranges. Clearly the Israeli military has its own estimates that it is not willing to share. All a spokesman would say was that they believed Hamas could sustain this level of fire for "a significant period of time".

The Palestinians are employing a variety of missiles, none of which, so far, appear to be especially new in terms of basic design. But the overall trend is for the weapons to have increased ranges and larger explosive payloads.

While the names and designations of specific missiles can be a bit confusing, Hamas has a huge inventory of shorter-range systems like the Qassam (up to 10km or 6 miles) and the Quds 101 (up to about 16km); bolstered by the Grad system (up to 55km); and the Sejil 55 (up to 55km). These probably make up the bulk of its inventory and for the shortest ranges can be bolstered by mortar fire.

But Hamas also operates a variety of longer-range systems like the M-75 (up to 75km); the Fajr (up to 100km); the R-160 (up to 120km); and some M-302s which have a range of up to 200km. So it is clear that Hamas has weapons that can target both Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, and threaten the whole coastal strip which contains the greatest density of Israel's population and critical infrastructure.

Streaks of light are seen as the Iron Dome system intercepts rockets near Ashkelon early on Wednesday

The Israeli military says that of the more than 1,000 or so rockets fired into Israel over the past three days, some 200 have actually fallen short in the Gaza Strip itself (perhaps an indicator of the problems of a home-grown and dispersed weapons manufacturing process).

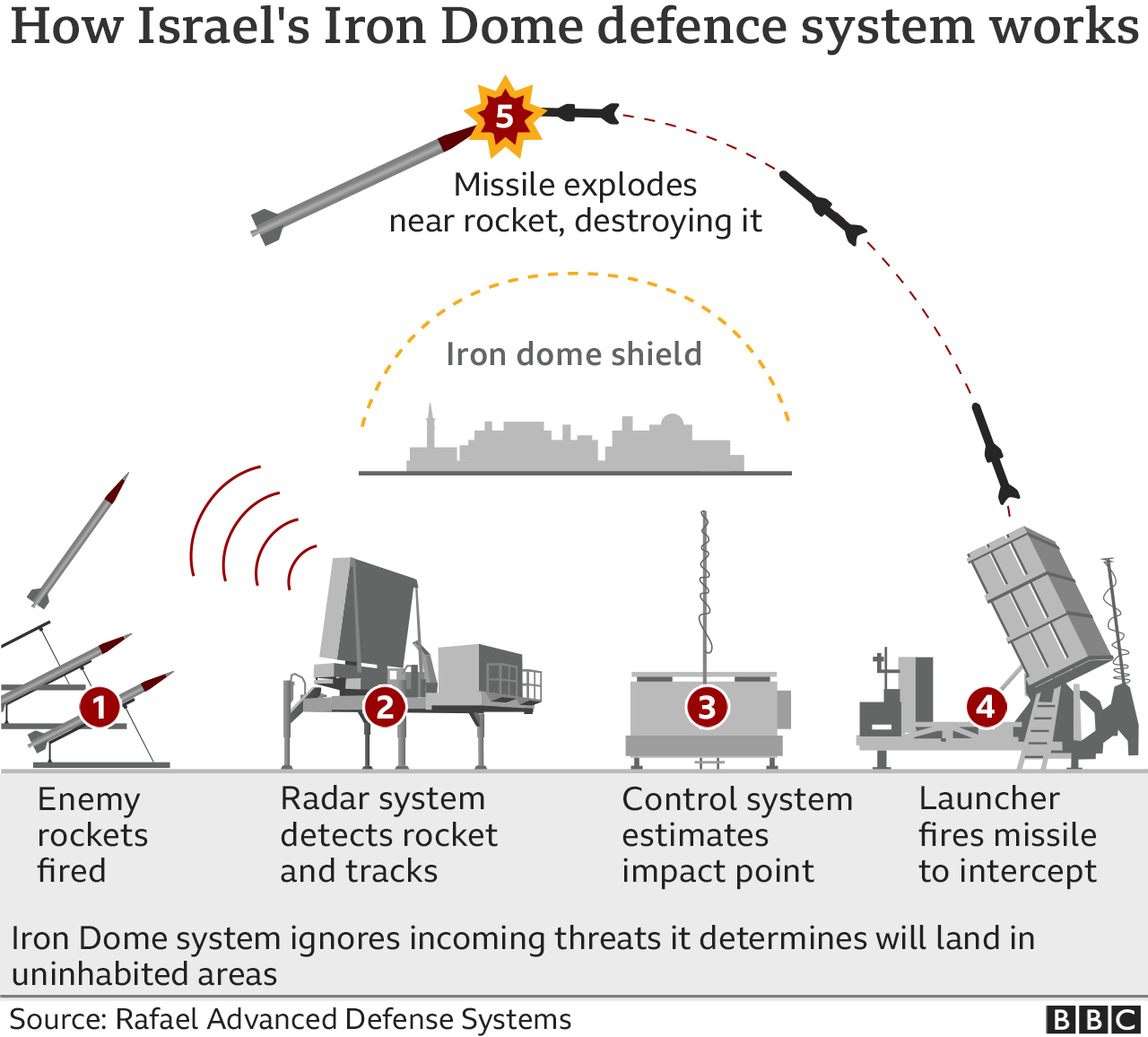

The IDF also say 90% of all missiles reaching Israel have been intercepted by their Iron Dome anti-missile system. However, at one stage the battery defending the city of Ashkelon appears to have been off-line due to a technical malfunction, underlining that for all its remarkable technical success, this is not a missile-proof screen.

To counter missile fire you only really have a limited number of options. You can employ anti-missile defences. You can target stockpiles and manufacturing facilities. You could in theory also mount a ground operation to push the missile-launchers back beyond effective range.

That is not going to be possible in this case. Part of the Palestinians' vulnerability is that they have no strategic depth and nowhere to go. A ground operation to stifle the missile fire is possible. But as was shown in Israel's last major incursion into Gaza in 2014, the human cost would be considerable. During the operation, 2,251 Palestinians, including 1,462 civilians, were killed, while on the Israeli side 67 soldiers and six civilians were killed.

This repeating cycle of rocket-fire, response and incursion gets neither side anywhere. At best, it buys a period of calm before the next round begins. Many might argue that it was the tensions in Jerusalem that started this particular episode. A signal once again that the Israel-Palestinian dispute cannot be ignored forever.

Hamas threatened to turn Ashkelon into "hell" in retaliation for Israeli air strikes

But with more and more Arab governments making their peace with Israel; with the Palestinians politically as divided as ever; and with this issue being far from the agenda of Israel's current leadership, it is hard to see how any progress towards a real peace can be made. For that you would need a real desire for progress on the ground and a strong and sustained effort by outside players. The conditions for this just do not appear to be there.

Jonathan Marcus is a foreign affairs analyst and former defence and diplomatic correspondent for BBC News