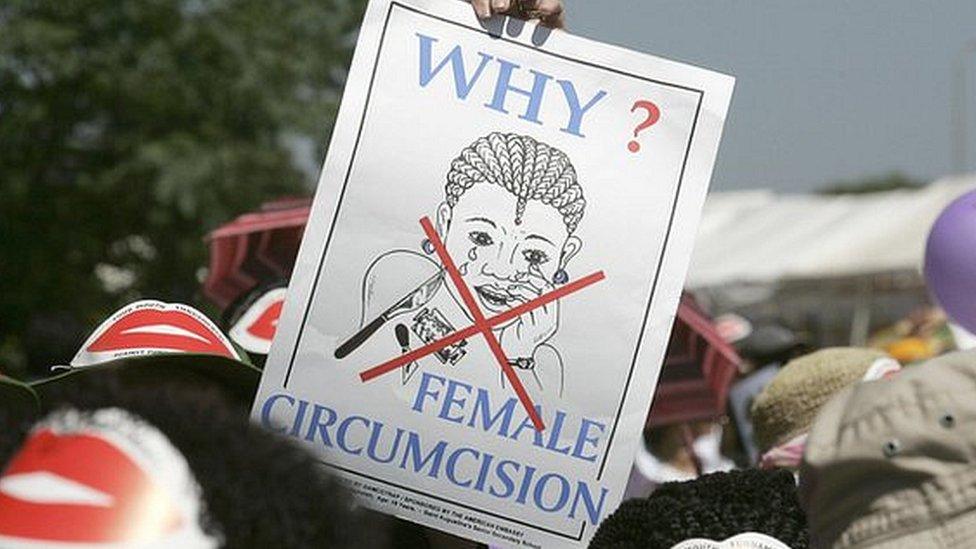

Female genital mutilation (FGM): 'I had it, but my daughters won't'

- Published

FGM has been banned in Egypt since 2008, yet the country still has one of the highest rates of the practice in the world.

Warning: This article contains graphic descriptions of female genital mutilation (FGM).

Among some conservative Muslim communities there, women are regarded as "unclean" and "not ready for marriage" unless FGM - the deliberate cutting or removal of a female's external genitalia - is performed. Under the law, doctors can be jailed for up to seven years if found guilty of carrying out the procedure, and anyone who requests it faces up to three years in prison.

Here, two victims describe what happened to them, and why they want to protect their own daughters.

Layla was about 11 years old when she was subjected to FGM. Nearly three decades on, that fateful day is still fresh in her mind. She had just passed her school exams when it happened.

"Instead of rewarding me for my good grades, my family got a midwife, dressed all in black, locked me in a room and surrounded me," she recalls.

"They held me down and she cut this part of my body. I didn't know what I had done wrong to these old people - whom I loved - for them to be on top of me and opening my legs to hurt me. It was psychologically like a nervous breakdown for me."

Her grandmother and neighbours were among those present.

"I wanted to play and feel free but I wasn't even able to walk, except with my legs wide apart," Layla says.

When she grew up and got married, she said she understood the consequences of not going through the painful ritual.

Layla says that for villagers a woman who has not undergone FGM is "necessarily a sinful woman", while a woman who has is seen as "a good woman".

"What does that have to do with behaving well?"

'Plastic surgery'

The ritual is still often performed under the pretext of "plastic surgery", according to Reda Eldanbouki, a human rights lawyer who heads the Cairo-based Women's Centre for Guidance and Legal Awareness (WCGLA).

Out of nearly 3,000 cases filed on behalf of women, the WCGLA has won about 1,800 of them, including at least six FGM cases.

The law might have been changed, but getting justice is another thing entirely. Even if they are caught, culprits find the system very lenient, Mr Eldanbouki says.

In 2013, a doctor was sent to prison for only three months for performing FGM on a 13-year-old girl. Mr Eldanbouki has met the girl's mother and the doctor who conducted it.

"The doctor says there was a growth between her legs, and he did plastic surgery, not FGM," Mr Eldanbouki says.

Even after the girl died as a result of FGM, her mother insisted she had done nothing wrong.

"We went to the mother and asked, 'If your daughter were still alive, would you still do it?' The mother said, 'Yes, after you do FGM, she is ready for marriage'."

Mr Eldanbouki says he faces a lot of harassment in his campaign against the tradition.

"When we were doing a workshop, a man spat at me and said 'You are trying to make our girls prostitutes, like in America.'"

'They held my legs'

Jamila, 39, underwent FGM when she was nine.

"My mother brought a midwife and some neighbours home. She prepared everything and left me alone with them in the room," Jamila recalls.

"They took off my shorts, and each of them held one of my legs. The midwife had a small blade which she used to cut this part of me, and that was it," she says.

In addition to the unbearable pain and the psychological scar created as a result of the surgery, Jamila says the experience changed her.

She had been outspoken, brave and smart at school before, but she would avoid adult women afterwards.

"I used to meet this midwife on my way to primary school. After what happened, I started taking a different route to avoid her. I thought that she would do it to me all over again."

Jamila still feels the pain when she is having sex with her husband.

Determined for her daughter not to endure the same experience, she even organised lectures by Mr Eldanbouki.

"I think he's the main reason why I was able to avoid doing it to my daughter. My husband's family also stopped doing it to their daughters."

Overall, the number of people who conduct FGM on their daughters is decreasing, says Jamila.

'Not my daughters'

Layla did not want her first daughter to go through the same pain, but she could not stop her husband arranging it.

But by the time Layla's other daughters were due to undergo FGM, the practice had been outlawed and lectures conducted by Mr Eldanbouki gave her the courage to protect them.

She knew how some girls in her community had bled to death following the ritual.

"Why should I expose my daughter to such a risk? I always knew it was wrong, but I didn't have the argument to convince others," Layla says.

"It was not only my husband I had to convince, it was my in-laws and my own family. They all went through this; all have a 'who do you think you are to change the world' attitude towards me."

After much persuasion, Layla's husband eventually agreed not to inflict any more FGM.

"But my heart still goes out to my eldest daughter," Layla says. "She bled a lot and I couldn't protect her."

Where is FGM practised?

The real names of Layla and Jamila have been changed in order to protect their identities.

This report was written with the assistance of BBC Arabic's Reem Fatthelbab. Illustrations by Jilla Dastmalchi.

- Published6 February 2019

- Published5 June 2020

- Published13 September 2016