Why Iraqi Kurds risk their lives to reach the West

- Published

Unidentified migrants prepare to cross the English Channel

Many of the 27 men, women and children who lost their lives in the English Channel on Wednesday as they tried to cross from France to the UK in an inflatable dinghy are believed to have been Kurds from Iraq.

Iraqi Kurds have also died in recent weeks on the border between Belarus and Poland, while hundreds more trying to get into the European Union are stranded there in freezing temperatures.

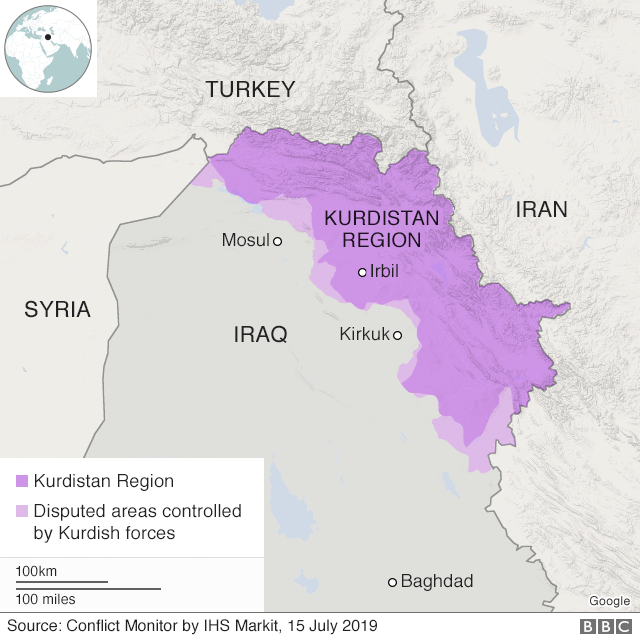

The tragedies have left many wondering why so many people from the semi-autonomous Kurdistan Region of Iraq, which has oil resources and a reputation for being relatively secure, stable and prosperous, would want to undertake such perilous journeys.

Many of the Iraqi Kurds stuck at camps dotted along the northern French coast and Belarus-Poland border say they are trying to escape economic hardship in the region and build better lives.

Iraqi Kurdistan is known for being relatively stable and secure

They complain about high unemployment, low pay and unpaid salaries, as well as poor public services, widespread corruption and the patronage networks linked to two main families - Barzani and Talabani - and their political parties, which have shared power for almost three decades.

"There is no hope in Kurdistan. Every young person has to migrate, except for those backed by the ruling parties," a young man at a camp in Dunkirk recently told Pishti News., external

A woman at the same camp said her husband had served in the region's Peshmerga security forces for years, but that they had left for Europe after he was not paid for months.

"We have hope for a better life once we reach [the UK], a better future for our kids."

Economic hardship

The Kurdistan Region has a population of more than five million, some 1.3 million of whom are employed by the government.

That means that many families suffered badly when the government cut public sector pay by up to 21% early last year and then failed to pay its employees at all for several months because of a financial crisis caused by the coronavirus pandemic, the related crash in global oil prices, and disagreements with the federal government in Baghdad over budget allocations.

Although the salary cuts were reversed this July, it is not clear if the workers have received the money they are owed.

Oil prices have now rebounded and the economy is recovering, but job shortages, low pay and poverty continue to trigger protests.

This week, thousands of university students have taken to the streets of the two biggest cities, Irbil and Sulaimaniya, to demand the restoration of monthly grants that were suspended in 2014 after another fall in oil prices and the start of the war with the jihadist group Islamic State (IS).

"There are students who can't afford to pay to travel home to the provinces, others who haven't got enough for three meals a day," one student told AFP news agency.

Some of the protests have become violent, with people setting fire to government buildings and offices of political parties. Security forces have detained dozens of students.

The government has faced criticism of its response to dissent. In May, the UN warned that journalists, human rights activists and protesters who questioned or criticised the authorities risked not only intimidation, restrictions on their movements and arbitrary arrests, but also prosecution on defamation and national security charges.

Fighting with Turkey

Escalating hostilities near the northern border with Turkey are also thought to be driving some emigration from the Kurdistan Region, with hundreds of people from two towns in Duhok province - Shiladze and nearby Deralok - reported to be among those who have sought to reach the European Union via Belarus since the spring.

The mountains that straddle the Turkish-Iraqi frontier are used as bases by the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK) rebel group, which has fought for Kurdish autonomy in Turkey since 1984 and is designated as a terrorist organisation by the US, UK and EU.

The Kurdish PKK has been fighting an insurgency since 1984

The Turkish military is said to have stepped up its attacks on the PKK since April, with warplanes and drones targeting PKK positions and high-ranking rebels, and Turkish soldiers battling PKK fighters on the ground inside northern Iraq.

Iraqi Kurdish officials say civilians have been killed in Turkish strikes, while several local Peshmerga fighters have died in attacks blamed on the PKK.

"Our area is besieged, it's in the hands of the PKK and the Turks. Our region is nice, but we are afraid and we don't trust in staying here," a man from Shiladze, whose 19-year-old son had travelled to Germany, told Reuters news agency last month.

Prime Minister Masrour Barzani has insisted that the recent exodus of Iraqi Kurds to Europe is "not a migrant issue, but a criminal human trafficking issue, with the migrants exploited by criminal networks and caught in a dispute between Belarus and the European Union."

He has appealed to European countries for help with stopping people smugglers, as well as financial assistance to support reforms and increased investment in the Kurdistan Region to help create jobs.

Mr Barzani has also asked for more aid to help the Kurdistan Region cope with continuing to host some 1 million Iraqis internally displaced by the three-year conflict with IS, and more than 200,000 registered refugees from Syria, who have strained health, education and other public services.

- Published25 November 2021

- Published25 November 2021

- Published13 December 2023

- Published15 October 2019