Crocodiles turn on humans amid Iran water crisis

- Published

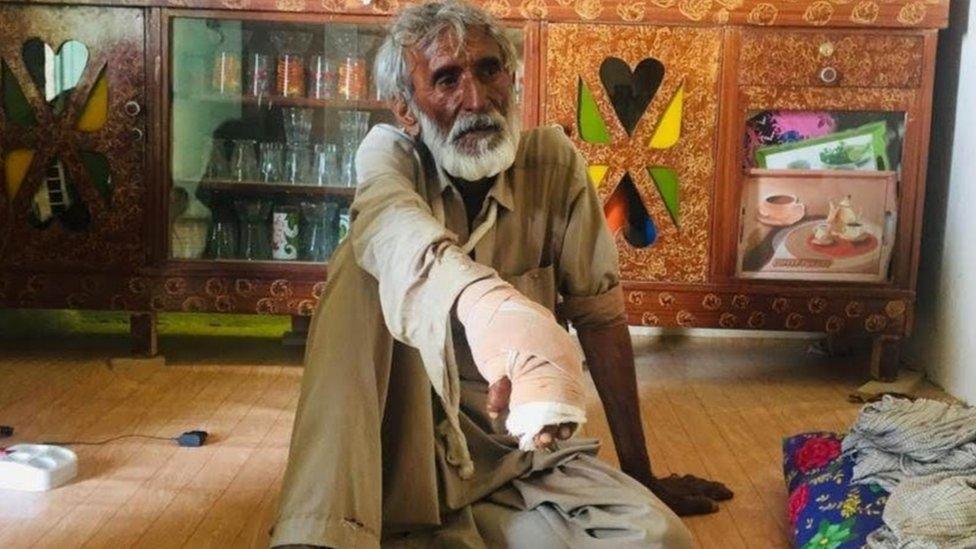

Siahouk, a shepherd, had gone to get water from a pond when he was attacked

Lying on the floor of his modest home, Siahouk was in excruciating pain from the injury to his right hand, the result of a nightmarish encounter. Just two days earlier, on a scorchingly hot August afternoon, the frail 70-year-old shepherd had gone to fetch water from a pond when he was pounced on by a gando, the local name for a mugger crocodile in Iran's Baluchistan region.

"I didn't see it coming," he remembers of the traumatic event two years ago, with the shock and disbelief still vivid in his eyes.

Siahouk was only able to escape once he "managed to squeeze the plastic [water] bottle in between its jaws", he says, reliving the moment as he rubs his bony face with his wrinkled left hand.

The blood loss left Siahouk unconscious for half an hour. He was only found after his flock of sheep returned unaccompanied to his tiny village of Dombak.

A lethal coexistence

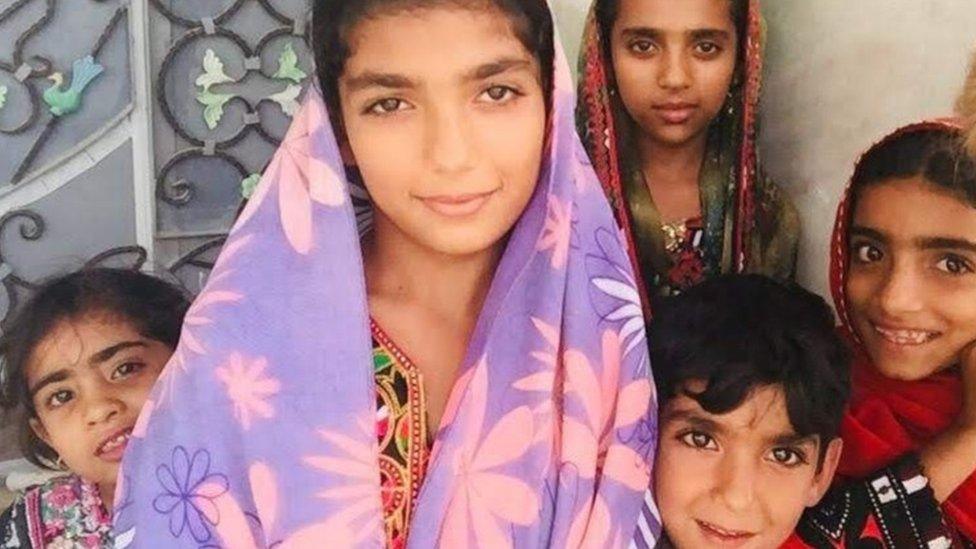

Siahouk's account echoes that of many other victims, mostly children. More often than not, emotive headlines about Baluchi kids suffering grisly wounds inundate Iranian media, yet quickly disappear.

In 2016, a nine-year-old called Alireza was swallowed by one such crocodile. And in July 2019, Hawa, 10, lost her right arm in an attack. Collecting water for laundry, she was almost dragged in by the crocodile before she was saved by her companions in a tug of war.

Many of the victims of attacks by gandos are children

The attacks have come at a time when Iran has been suffering acute water shortages and, consequentially, fast-shrinking natural habitats have seen the gandos' food supplies dry up. The starving animals treat humans approaching their territory either as prey or a menace to their evaporating resources.

Scattered across Iran and the Indian subcontinent, gandos are broad-snouted crocodiles, classed as "vulnerable" by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Iran has an estimated 400, comprising nearly 5% of the species. Iran's Department of Environment says it is doing its utmost to strike a balance between preserving the gandos and protecting local people.

A gando crocodile peers out of the River Bahu-Kalat

Despite all the thirst-driven tragedies in recent years, there is little sign of the pledge being put into effect. Traveling alongside River Bahu-Kalat, the gandos' main habitat in Iran, there are hardly any signposts warning about the danger.

In the absence of a calibrated government strategy, volunteers have stepped in to try to save the species by quenching their thirst and satiating their hunger.

In Bahu-Kalat, a village named after the river, up the dirt road from Dombak, I sit down with Malek-Dinar, who has been living with gandos for years.

"I have killed my garden to bank water for these creatures," he says of his land once thriving with bananas, lemons and mangoes.

Malek-Dinar feeds gandos in the river near his home because their typical prey has become scarce

The river in the vicinity is home to a number of those crocodiles he regularly feeds with chicken breasts, because "the killer heat has left frogs and their typical prey scarce".

"Come on, come here," Malek-Dinar repeatedly summons the crocodiles, while asking me to keep a safe distance. In the blink of an eye, two show up, waiting to be fed their ration of chicken from the familiar white bucket.

'Who can survive without water?'

Iran's water scarcity is not unique to Baluchistan. Deadly protests erupted in the oil-rich south-western Khuzestan province in July. And in late November, riot police in the central city of Isfahan fired birdshot at protesters gathered in the dried-up bed of the River Zayandeh-Roud.

With global warming already showing its ugly face in Iran, the implications for Baluchistan could be catastrophic when coupled with decades of water mismanagement.

After pulling over in Shir-Mohammad Bazar to shelter from a dust storm I meet women doing laundry in the open.

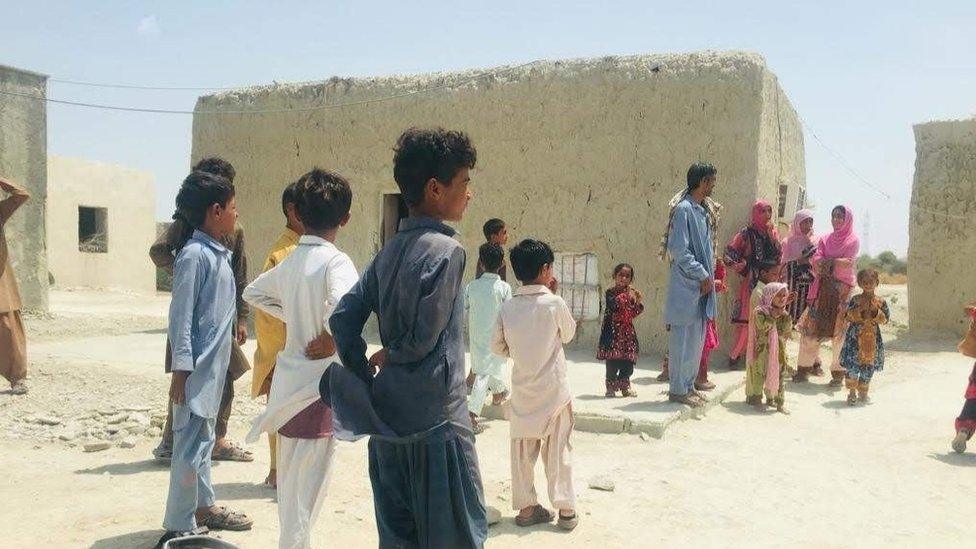

Iran has suffered water shortages due to climate change and poor resource management

"There is piping infrastructure but no running water," 35-year-old Malek-Naz tells me. Her husband, Osman, smirks at my question about showers, pointing to the sight of a woman bathing her son in a vessel of salty water next door.

Osman, a father of five, and his cousin, Noushervan, who joins the conversation, make a living transporting petrol to neighbouring Pakistan, where it can be sold for more than at home.

"There are numerous risks," Noushervan admits, albeit in a defiant tone. "But let it be when there is no job." And the risk has been real. In February, Iran's border guards opened fire on a group of "fuel smugglers", killing at least 10.

Such crackdowns are commonplace in the sensitive border area, where successive Iranian administrations have worried about security.

The Baluchistan region is one of the least developed and poorest parts of Iran

"They are wilfully turning a blind eye to our anguish. Trust me, we are no enemy of the state," Osman says, complaining of what he and many disillusioned Baluchis describe as "systematic neglect" of the community.

Still, to him and a countless more Baluchis, unemployment is far less of a challenge than the water shortages that have turned even gandos - the "blissful" creatures with whom they once peacefully coexisted - against them.

"We don't expect any government handout. We don't expect them to put jobs on a platter for us," says Noushervan. "We Baluchis can survive on loaves of bread in a desert. But water is the essence of life. We won't survive without it, and who does?"

You may also be interested in:

Strolling crocodile sparks panic in India village

Related topics

- Published31 January 2019

- Published15 June 2016