Jeddah demolitions provoke rare display of dissent in Saudi Arabia

- Published

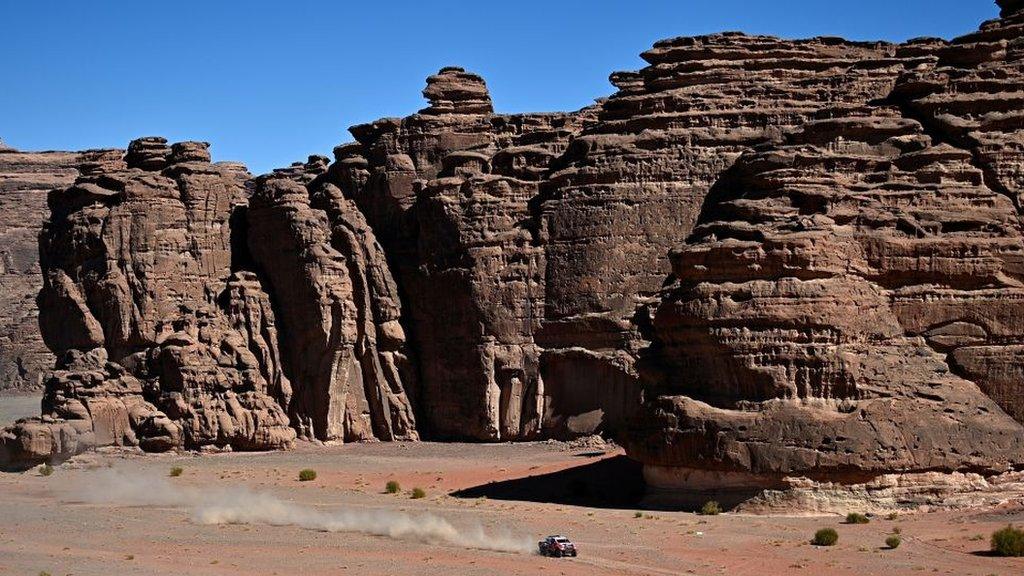

Whole areas of Saudi Arabia's second city are being razed to make way for a new development.

Residents of districts recently razed to the ground for a multi-billion dollar development in the city of Jeddah in Saudi Arabia have complained that they did not receive adequate warning or compensation when their homes and neighbourhoods were demolished.

The Saudi authorities defined the areas that cover a substantial slice of the older parts of Jeddah as slums - vilifying them as dens of crime and vice.

Those living there have denied this, saying that they are long-established districts that provide affordable housing for the less well-off amongst both Saudis and expatriates

Their anger has produced a rare outpouring of protest in Saudi Arabia on social media platforms, such as Twitter and TikTok, bemoaning what they see as the injustice and inequity of the plan to transform the area.

Bulldozers have left a swathe of Jeddah in ruins - some have described the scene as resembling the aftermath of war.

Videos showing large apartment buildings crumbling to dust beneath the wrecking ball have proliferated online. For several weeks the hashtag "hadad_jeddah, external" - "Jeddah_demolition" in Arabic - was trending on Twitter.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

One video showed people waving goodbye to various cherished landmarks, external in the Jeddah Central area that were slated for destruction.

Some of those who grew up in Saudi Arabia's second city waxed lyrical about the area, which was once the centre of the city, but has become run down in recent decades.

A Saudi activist known online as Wajeeh Lion described the project to the BBC as erasing the city's history.

But that is not how the authorities see it.

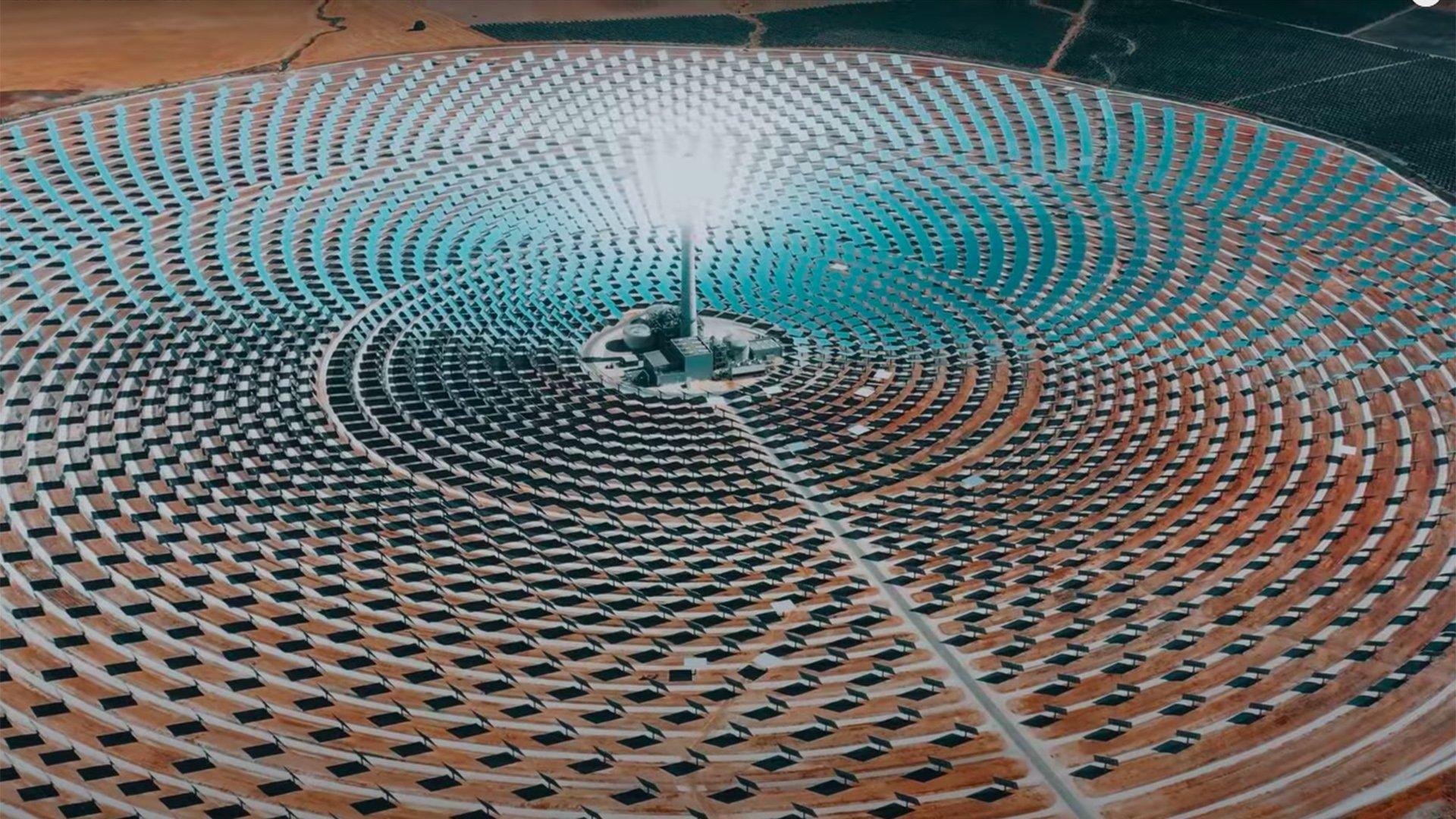

The redevelopment - which is officially budgeted at $20bn (£15bn) - is portrayed not just as an upgrading and modernisation of these neighbourhoods, but a restoration of their cultural and historical value in a port city that's served as a trading post between East and West for thousands of years - as well as the entry point for countless Muslim pilgrims on their way to Mecca for Hajj each year.

The historic heart of Jeddah is home to buildings dating back to the 7th Century

The plans include an opera house, an oceanarium, a sports stadium, a marina and the creation of a large public beach.

Some existing landmarks will remain - including the imposing Tahlia water tower, which will be turned into an industrial museum.

More than 17,000 residential units will also be built, according to the official plans.

But those who have made their homes in the area say that they and those like them will be excluded from such plush and expensive real estate.

A businessman with property in the neighbourhoods under demolition - who wanted only to be referred to by the initials KM - told the BBC that he could not believe his eyes when he returned to the area this week after two months away.

"You would never believe," he said, "that there used to be buildings and communities in the areas that have been flattened."

He said that many of those made homeless had now moved out to rural areas where rents were still cheap or moved in with their families where possible.

Residents complain that they were not given adequate warning or compensation

As for his own situation, KM said that he had recently invested a considerable amount of money in commercial units and offices - but despite having all the necessary permits, the two buildings were being brought down and he had no indication that he would receive proper compensation form the authorities.

In a number of online forums, those affected by the situation tell similar stories about not being given sufficient warning. Many say that government promises of compensation or alternative housing have been limited so far.

They also say they believe the districts have been targeted partly because they are home to different nationalities - the cosmopolitan, outward-looking nature of Jeddah is one of the characteristics that locals have long prided themselves on.

The districts being demolished are where generations of pilgrims have stayed on after Hajj to make a life there - some becoming citizens.

The majority, though, are from poorer regions of the world, doing the often harsh manual labour on which modern Saudi Arabia has been built, but with no permanent residential rights. One resident described the redevelopment to the BBC as a form of ethnic cleansing.

Many of those made homeless had been forced to move to rural areas or move in with their families

Residents have been outraged at government attempts to demonise them as drug dealers, criminals and prostitutes and to dismiss the whole area as a slum.

KM concedes that two or three of the districts could be considered slums, but he says the rest are functioning neighbourhoods that contain every amenity and provide decent homes for those priced out of other upmarket areas in Jeddah.

The clamour over the project has somewhat faded in the past couple of weeks - perhaps as the destruction of much of the area becomes a fait accompli. Raising your voice in Saudi Arabia in opposition to any such change is a risky venture in any case.

But the resentment and sense of injustice remains among those who feel they have been summarily deprived of their homes in pursuit of a new vision of Saudi Arabia - as a rival to Dubai for investors and tourists - that holds no place for them.

Related topics

- Published22 February 2022

- Published23 April 2020