Iraqis fear another false dawn after politicians break year-long deadlock

- Published

Protesters are bleak about the future after a year of violent unrest and political paralysis

Iraq is at a crossroads. For more than a year, the country has been without a properly functioning government, as politicians failed to agree on who to lead it.

And in recent months, the capital Baghdad has been gripped by deadly clashes.

On Thursday, parliament took a key step towards forming a government by electing a new president, Kurdish politician Abdul Latif Rashid.

He immediately designated Mohammed Shia al-Sudani, the Shia Muslim nominee of the largest parliamentary bloc, to be prime minister. He will have a month to form a government.

But there have been many false dawns over the past year.

And at a Baghdad market, many people are sceptical about the future. They believe all politicians are serving their own ends.

Political conflicts in Iraq are unlike those in any other country. They is always a risk of them descending into chaos. Weapons here are largely out of the government's control, and all the main political rivals are armed to the teeth.

'Who will protect us?'

Mustafa Rahim is a wealthy merchant, who owns a multi-million dollar wholesale business.

He has laid off nearly one third of his workers over the past year. He tells me his sales have dropped by 70%. Uncertainty is his business's worst enemy.

Business is tough for Mustafa Rahim, as the political crisis bites

Mustafa fears for his life too.

"Wealthy people are the first to be targeted if there happens to be looting. We have gangs and militias in this country. We might get kidnapped," he says.

"Also, we don't want Iraq to go back to square one, when we had sectarian tension and lax security.

"All Iraqi sects work in this market. If there's a civil conflict, who will protect us?"

The peak of sectarian violence in Iraq was back in 2006 and 2007, when members of the main Shia and Sunni Muslim sects engaged in tit-for-tat killings. Tens of thousands of people were killed. No one wants to see these days again.

'We are scared'

Although life in Baghdad is more or less business as usual, there is an underlying fear that I clearly feel as I speak to more people in the market.

"I am an old man. It's not about me now but about the life of my children" a merchant tells me. He says his son does not want to go to school due to the current instability.

Iraqis thought they would be able to give their children a better life

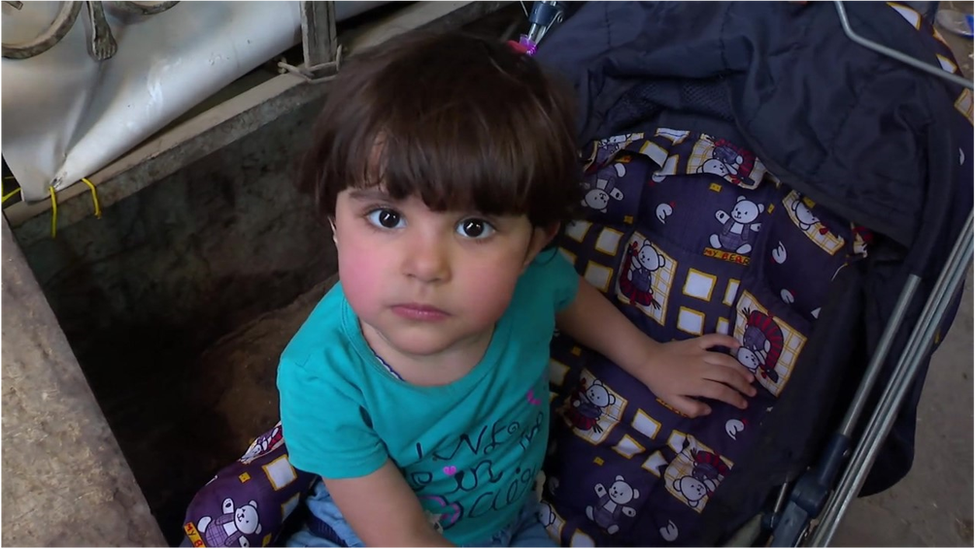

A family out shopping echo this.

"We are quite scared. I can't see a future for my children here," says a young mother.

"We've been hoping for a better life since 2003 but nothing has changed," she adds, referring to the US-led invasion that toppled Saddam Hussein.

Shia rivals

Tensions rose when influential Shia cleric Moqtada al-Sadr ordered his 73 MPs to withdraw from parliament in June.

His party won the most seats in the October 2021 election, but he and his Kurdish and Sunni Arab allies were unable form a government after he refused to negotiate with rival Shia groups backed by neighbouring Iran.

Supporters of the influential Shia cleric Moqtadr al-Sadr have been at odds with those of rival Shia factions

A few weeks after Mr Sadr ordered his to MPs resign, the cleric's supporters stormed the fortified Green Zone in Baghdad, where parliament sits, disrupting attempts by his rivals to form a government.

In August, dozens of people were killed as Sadr supporters clashed with security forces and rival militias in the Green Zone.

Hassan, a young man in his 30s, was one of them.

Hassan, a supporter of Moqtada al-Sadr, was one of those killed in clashes in Baghdad in August

"Hassan took my heart away. Since he died, my life has become unbearable," says Umm Hassan, his grieving mother.

A photo of Moqtada al-Sadr is hanging on the wall of the family's home. His mother insists he was a peaceful loyalist of the Shia leader.

She tells me she comes to his bedroom twice a day to be close to him.

When I visited, Hassan's father was out, undergoing medical tests at a nearby hospital.

Umm Hassan says she does not know who killed her son

Umm Hassan tells me his health has deteriorated due to grief.

The family will now struggle to make ends meet as he was the main breadwinner.

"We don't know who killed him. He was not only my son but my everything," she says.

'We trust no-one'

Iraq does not appear to getting any respite despite the bumper oil revenues it is generating.

It has started to recover from a long, draining fight against the jihadist group Islamic State (IS).

Now, it has been caught up in a volatile, unpredictable power struggle between heavily armed Shia blocs.

In early October, protesters took to the streets of Baghdad to mark the third anniversary of the start of a protest movement sparked by widespread anger at endemic corruption, high unemployment, dire public services and foreign interference.

An Iraqi protester holds a sign reading 'Brother don't kill me'

The movement, known as Tishreen (October), called an overhaul of the post-2003 political system based on sectarian and ethnic identity, which has allowed a narrow elite to keep a firm grip on power and encouraged corruption.

'We have zero confidence in all politicians. We trust no-one," one protester tells me.

"Since 2003, they kept promising us better lives but it all turned out to be a bunch of lies. We've had the same faces running this country over the past 19 years."

Tishreen is non-partisan and rejects Iraq's dominant political groups and militias.

"We didn't choose any of these political parties. The US occupation forces did that and Iran kept them in power," says another protester.

Iraqis are exhausted and disappointed.

A young man holding the Iraqi flag speaks for many when he says: "The Iraq I dream of is as far away as ever."