How Iran’s economic woes created conditions ripe for protests

- Published

Women have been waving their headscarves in the air and setting them on fire at protests

For the past four weeks, the cries of "woman, life, freedom" and "death to the dictator" have been heard in dozens of cities across Iran, as protesters have vented their anger at the country's mandatory hijab laws and the Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

The protests were sparked by the death last month of Mahsa Amini, a 22-year-old woman who fell into a coma after being detained by the morality police for allegedly failing to cover her head sufficiently.

Although people have been taking to the streets to express their anger at the political and social repression in the Islamic Republic, the state of the economy had already created a sense of despair.

A shrunken economy

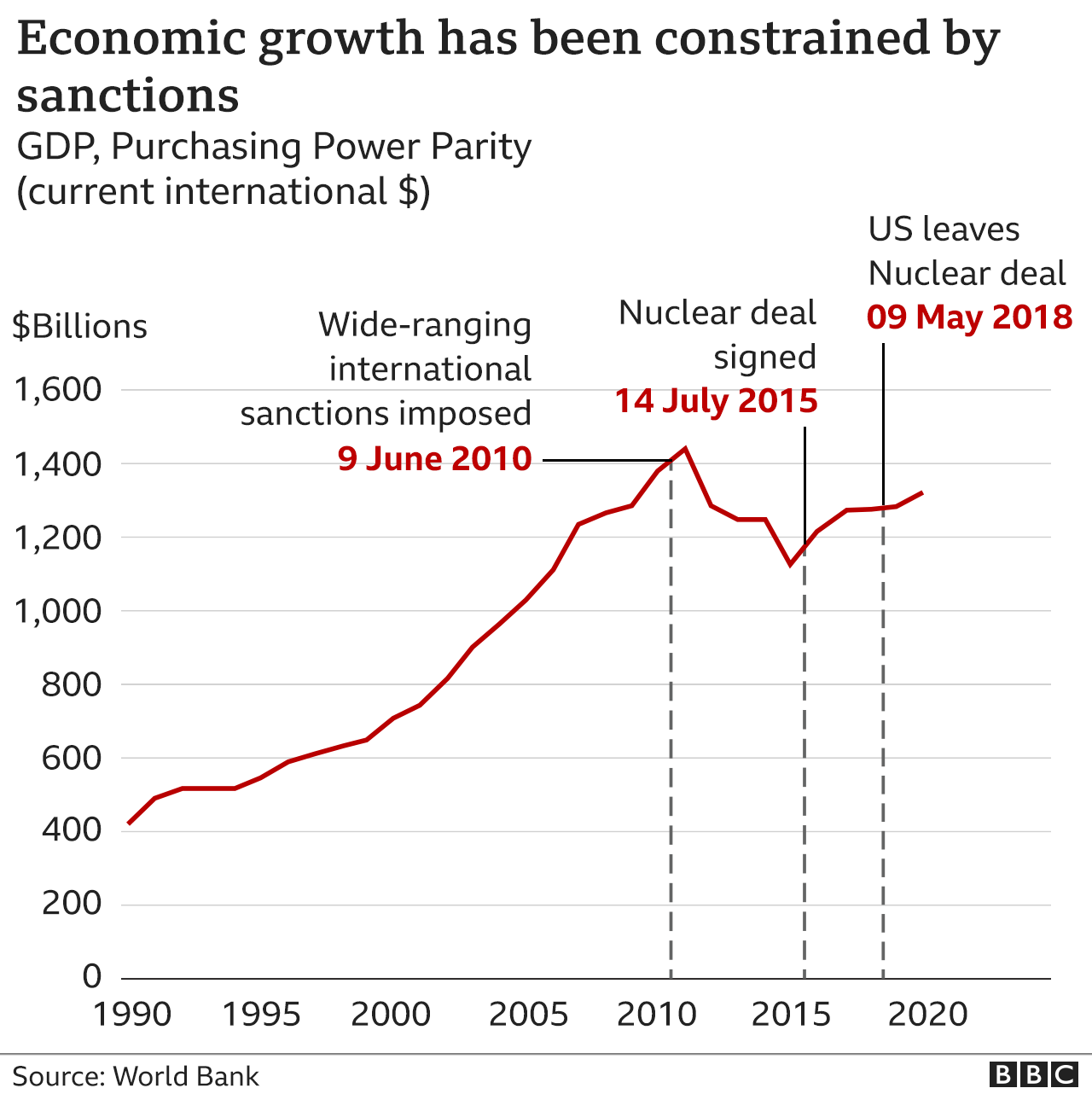

From 1990 to the late 2000s, the Iranian economy was on an upward trajectory. But it started to decline after world powers imposed crippling sanctions in an effort to make Iran's leaders agree to limit its nuclear activities.

The 2015 nuclear deal brought relief from those sanctions. However, the economic benefits were short-lived, as less than three years later, then US President Donald Trump abandoned the deal and reinstated US sanctions that halted most of Iran's oil exports.

The sanctions, coupled with economic mismanagement and corruption, have meant that the Iranian economy has not had any substantive growth in the past decade. And by some measures, it is still 4-8% smaller than it was back in 2010.

Women out of work

With a stagnant economy, it is no surprise that the total number of people in work has hardly changed over the past decade or so. It has hovered around 23 million, despite the population growing from 75 million to 85 million.

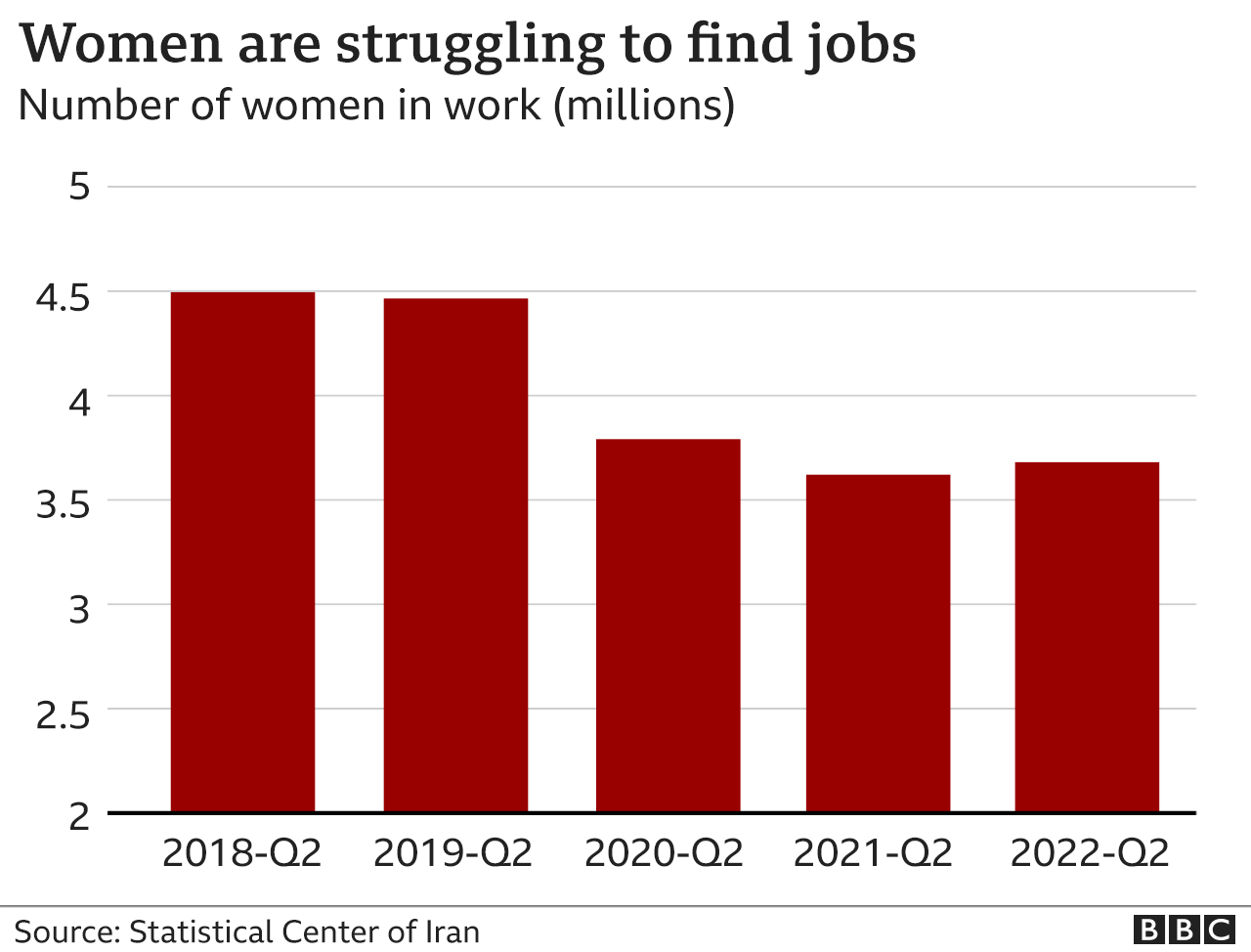

And women have had it worse than men, especially in the last few years. The government's pursuit of higher birth rates and emphasising women's role as stay-at-home mothers - under the orders of the supreme leader - has resulted in a significant decline in the number of women in work.

In the past four years, while the number of working men has risen slightly, the number of women in work has decreased by a fifth.

The outlook is particularly grim for female university graduates. The unemployment rate amongst them currently stands at 22.3% - more than twice the rate among male graduates.

Sky-rocketing prices

While many countries are suddenly having to grapple with double-digit rates of inflation, they have been the norm in Iran for many years.

As a result, the cost of goods and services has increased by 1,135% over the past decade.

The rise in food prices is even more staggering. Chicken is almost 20 times more expensive than 10 years ago, while the price of cooking oil is 40 times higher.

Earlier this year, the government's decision to stop subsidising imports of things such as cattle feed, wheat flour and vegetable oil led to the prices of many food items such as pasta, dairy and meat shooting up overnight.

In just one month, food prices increased by 26%, while the overall rate of inflation is projected to reach 47% by March 2023.

Back in the spring, Maryam (not her real name) told BBC Persian that she had given up the idea of buying meat or fruit.

"You can survive without buying fruit. But it has been four months since I ran out of rice and I can't afford to buy any. Buying meat has become impossible," she said.

A devalued currency

Over the past five years, the value of Iran's currency, the rial, has fallen by almost 90%. Back in 2017, one US dollar on the open market was worth just under 40,000 rials. Today, it is worth more than 330,000 rials.

Most of the fall in the rial's value happened in late 2017 and early 2018, when it became clear that the United States intended to withdraw from the Iran nuclear deal, impose stinging sanctions on Iran's main source of foreign income and severely restrict its access to the global banking system.

Falling living standards

All these factors have combined to cause a long slump in living standards.

Figures show the average annual household consumption in Iran improved significantly between the early 1990s and the mid-2000s. But since then, it has declined by 29% in cities and almost 50% in rural areas.

In other words, Iranian families are, on average, quite a lot poorer than they were 15 years ago.

Bleak prospects

It is not difficult to understand the sense of despair that many young Iranians feel about their lives.

With the prospects of the US returning to the nuclear deal and lifting its sanctions having dimmed in recent months, Iran is set to remain an isolated country, with the government relying on selling oil on the so-called grey market to make ends meet.

Iranian authorities, and especially the supreme leader, want to build a "resistance economy". They want Iran to be even more inward-looking and economically self-reliant, so that they can continue their anti-American and anti-Israel foreign policies.

But with little hope of better, more prosperous lives in the future, many Iranians have taken aim at the whole Islamic Republic during the recent protests.

Related topics

- Published6 October 2022

- Published5 October 2022

- Published5 October 2022

- Published4 October 2022

- Published17 September 2022