One careful step at a time through Lebanon’s minefields

- Published

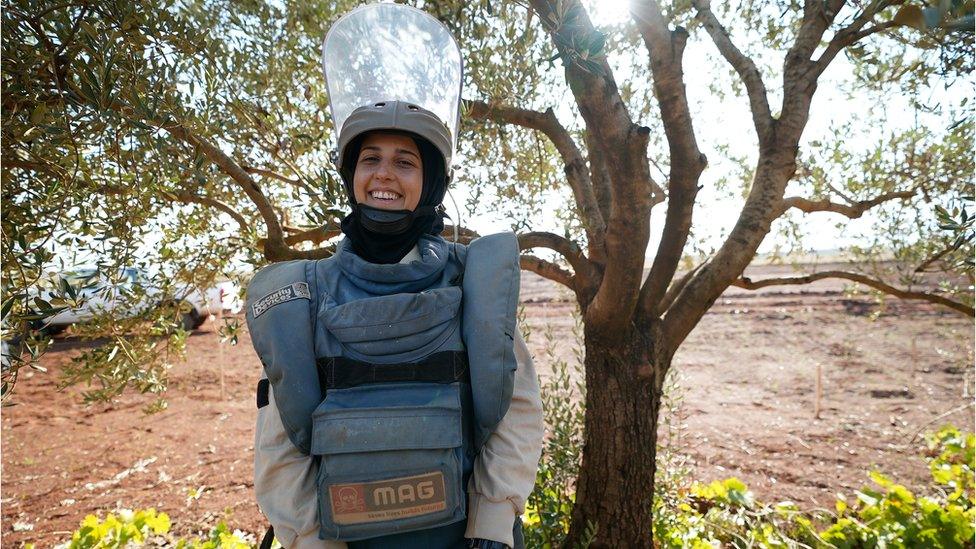

The demining teams in Lebanon need to wear heavy protective gear and begin their work early to avoid the stifling temperatures

A visit to a minefield starts with some crucial safety notes. And they will save your life - when you are just steps away from deadly buried explosives, you need to pay attention.

Red-painted sticks dug into the ground mean danger. Tread any further and you risk stepping right onto a mine. White sticks are the sign of a safe, cleared channel. Black sticks show where an anti-tank mine used to lie, with the explosives inside now burnt away.

Wearing protective gear is vital. That means a helmet with a visor that wraps around your face from ear to ear and covers well below the chin. Protective body armour drops almost to your knees, shielding your vital organs and arteries from the impact of any accidental blast.

In the heat of the Lebanese summer, it is stifling. Deminers start their work as soon as the sun rises, to catch the coolest temperatures. Every hour they take 10 minutes to rest. As the noon sun hits its highest point they are almost finished for the day. It is too dangerous to work when the conditions mean you might lose concentration. Even a momentary slip can be fatal.

It was 25 years ago this month, on 3 December 1997, that the Ottawa treaty was signed. It's better known as the Mine Ban Treaty - the international agreement that banned antipersonnel landmines - and it is widely considered to be one of the world's most successful disarmament treaties. To date, 164 countries have agreed to be bound by it.

Just weeks before the treaty was signed, the Mines Advisory Group (MAG) won the Nobel Peace Prize for their mine action efforts around the world. They have been working here in Lebanon since 2001. The demining operation is huge and continues almost daily. This year alone they will clear two million square metres of land and destroy around 10,000 landmines.

Staff working with the Mines Advisory Group (MAG) have destroyed 10,000 landmines this year alone

As well as dealing with both cluster munitions in the Bekaa Valley and improvised explosive devices (IEDs) left by the Islamic State group (IS) in the north-east of the country, the main work involves demining the frontier between Lebanon and Israel.

The so-called Blue Line was drawn by the United Nations in 2000, designed to physically mark the withdrawal of Israeli forces from the south of Lebanon. In some parts it is a high wall, in others little more than a metal fence that you can see right through. Below the surface is a 120km (75 mile) minefield designed to form an impenetrable barrier. Around 400,000 mines were laid there, some of them barely a metre apart.

In the village of Arab Ellouaizi, the barrier that marks the end of Lebanon and the start of Israel sits right at the edge of the mined area. A metre or two beyond it an Israeli military tower rises behind the grey concrete blocks. The hills in the distance are swathed in mist.

This heavily-mined land is a dangerous problem for the large number of refugees who have come to Lebanon from Syria. They want to live on the land, and cultivate it, but they don't know the risks.

Three quarters of Arab Ellouaizi's population are Syrian refugees trying to carve out a living hundreds of miles from home. And that's why there's another vital reason - apart from safety - to clear this area. Agriculture is the main work in the south, and farmers are desperate to have the land cleaned up so they can use it. Lebanon's crippling financial crisis, coupled with the food shortage caused by the war in Ukraine, means ever more farming is an urgent priority.

Farmers in the area are desperate to have their land cleared so they can grow crops to help address the food shortages

Abu Ghassan Awada has a crop of peppers that are plump and ready to harvest. Above them, peach trees reach up over our heads. He remembers the sound of explosions at night when goats, sheep and foxes strayed onto the mines. It meant that for years, he couldn't farm his land. "I used to just be a worker, hired by other people. But now I can hire people to work on my own plot," he says. He still takes time to maintain and fix the metal fence that marks out the edge of his farm. Beyond it, just metres away, the land is still an active minefield. He knows not to stray towards it.

Some of MAG's longest-serving staff have been part of the team for decades. A large cedar tree poster in the doorway of their headquarters shows their names and faces. Hiba Ghandour is MAG's programme manager in Lebanon. She's also passionate about making sure as many women as men are involved in the demining work. "When we're announcing the jobs we have to fill, even adding a photo of a woman doing the job makes sure we can reach everybody," she explains.

One of those women is Suaad Hoteit. She started the job four years ago, and even met her fiancé as they worked together in the minefield. Deftly pulling her helmet onto her head, she describes the day's work. "I take my detector, then I go to the field and start searching. When I find a mine, I call the supervisor to check it. And at the end of the day, I make an explosion."

Suaad Hoteit began clearing mines four years ago, and even met her fiancé as they worked together in the minefield

I'm surprised by the matter-of-fact way she talks about something so dangerous. "It's four years now, so it's a daily routine," she smiles. "In the first year of being here, I was so scared. Now I understand the danger. And I work here because I want to show people that women can do anything. We are strong and independent."

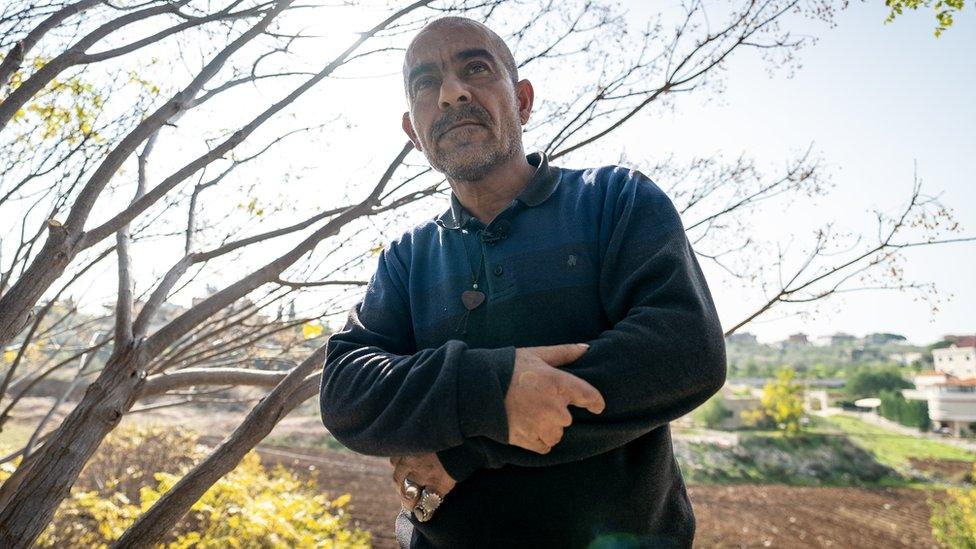

The type of landmines Suaad is searching for still regularly injure and kill people in 60 different countries. Worldwide, there are around 15 casualties every day. Haidar Maarouf Haidar was one of them. He wears a special white elastic support on his right hand, and peels it off carefully as he recalls the day when he detonated a mine while planting trees in his garden. The moment is still clear in his memory, even though it happened two years ago. "Suddenly something exploded and I heard a sound, as if I was in a dream. I didn't know what had happened. One moment I was leaning on the ground and the next suddenly something went off. I was knocked unconscious and when I woke up I couldn't see my fingers. They were gone."

Haidar turns his hand to show me what remains of the fingers - just four stumps twisting away from the palm. "My psychological state has changed, that's the first thing. I was a daily worker, I used to do everything with my hands, breaking stones and lumber with them. My body was active. Now if I use my hands, it feels like an electric current in them. My leg injuries make it difficult to walk. My life has totally changed, I can't do any work anymore except raising my children."

Haidar Maarouf Haidar lost the tips of his fingers on one hand when a mine detonated while he was planting trees in his garden

After so much pain the finish line is now in sight - in Lebanon at least. As we stand together in the Arab Ellouaizi minefield, MAG's Hiba Ghandour wants to point out how far they have come. "Overall in Lebanon we've cleared 80% of the contaminated land. We just need to keep going, and it's the support of our international donors that makes it possible."

Countries like the US, France, Norway, the Netherlands and Japan are at the forefront of mine action funding. The help is vital, but the amount of money pledged is decreasing. In Lebanon alone it has fallen from $19.7m (£16m) in 2019 to an anticipated $12.1m in 2023.

It is hard to predict how long it will take to clear the remaining 20% of contaminated Lebanese land. Fluctuating funding is one reason. But new technologies play a big part in the timescale, too. In the last year a new machine - called a rubble crusher - has drastically speeded-up the process of destroying mines. It swallows up both the earth and its hidden devices, breaking them to pieces before they explode. Sometimes they detonate inside the machine, and the thick armour-plating contains the blast. It doesn't replace human deminers, because it can only work on flat terrain. But it definitely makes the job quicker.

Demining has been helped by new technologies, such as the so-called "rubble crusher", in which mines sometimes detonate inside

Some of the bigger munitions - the anti-tank mines - are also being dealt with in a new and special way. The demining teams are now so close to the politically-sensitive boundary between Lebanon and Israel that blowing up the large mines risk physically damaging it. That would not be good for the fragile relations between the two countries. So now, special sticks of thermite are inserted into the mines in the ground where they lie. The intense heat burns away the explosives without creating a huge blast.

Within sight of the fierce flames Mohammed Atris caresses the fresh green shoots that cover his land. For decades the ground he owns has been unusable, loaded with mines. Even walking on it was out of the question. "I felt sad, depressed and frustrated," he tells me. "I can't describe the feeling of being unable to use the land that we grew on earlier in our lives before it was mined and made unfit for farming. It was awful."

The vegetables he is tending were planted just six weeks ago, only 24 hours after the land was declared clear and handed back to him. "I couldn't wait. To all of those who made this happen, we thank you for your efforts."

Crouching to pull up his new crops, he gently wipes the soil from their roots and breaks into a beaming smile.

Related topics

- Published18 November 2022

- Published30 October 2022

- Published11 October 2022