Secretive Saudi executions leave families in the dark

- Published

Saudi Arabia executed 81 prisoners on 12 March 2022, including these nine men

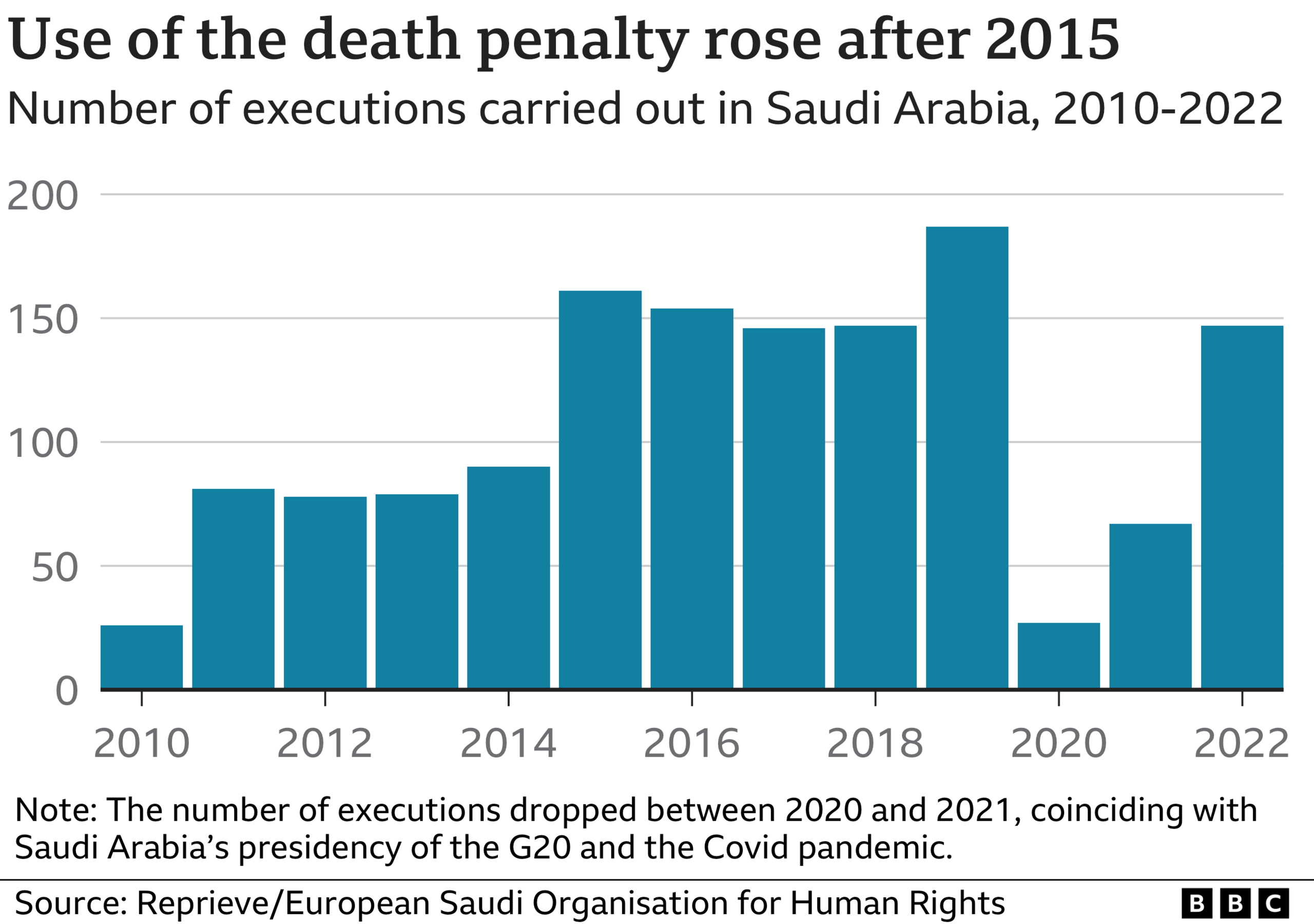

Executions of prisoners have been carried out in Saudi Arabia with no advance warning to their families, relatives have told the BBC. The country's execution rate has almost doubled since 2015 - according to a new human rights report - the year when King Salman and his son Mohammed bin Salman took charge.

Mustafa al-Khayyat's family were given no notice that he was about to be killed.

They still have no body to bury. No grave to visit. The last they heard from him was a phone call from prison, and he signed off with these words to his mother: "Alright, I have to go. I'm glad you're OK."

Neither had any inkling that it would be the last time they spoke.

A month later, Mustafa was dead - one of 81 men killed on 12 March 2022, in the largest mass execution in modern Saudi history.

Mustafa's name is on a long and growing list put together by the campaign group Reprieve - which, along with the European Saudi Organisation for Human Rights, has been meticulously documenting Saudi executions for a new report.

Based on data collected since 2010, their study, external has found that:

Saudi Arabia's execution rate has almost doubled since King Salman took the reins in 2015, appointing his son Mohammed bin Salman to key positions

The death penalty has been routinely used to silence dissidents and protesters, contravening international human rights law, which states it should only be used for the most serious crimes

At least 11 people initially detained when they were children have been executed since 2015, despite Saudi Arabia's repeated claims that it is curtailing the use of the death penalty against minors

Torture is "endemic" in Saudi prisons, even for child defendants

Reprieve documented 147 executions in Saudi Arabia last year, but says there could well have been more. It also says the country has "disproportionately" used the death penalty against foreign nationals - including female domestic workers and low-level drug offenders.

Nearly a year on, officials haven't told Mustafa's family how he and the others were executed. His older brother, Yasser, says it has been a tragedy for the families.

"We don't know whether they were given a decent burial or thrown in the desert or in the sea. We've no idea."

Mustafa al-Khayyat holding his baby nephew

Yasser is speaking publicly for the first time. He now lives in Germany, where he has been given political asylum after fleeing Saudi Arabia in 2016, fearing the same fate suffered by his brother.

Yasser says his brother was "fun, sociable, and popular". Since 2011, Mustafa took part in daily demonstrations - led by the country's Shia minority - against the Saudi government.

He was detained in 2014. After his death, an official announcement said that he, along with 30 others, had been executed for the same string of offences - including attempted murder of security personnel, rape, robbery, bomb-making, stirring up strife and spreading chaos as well as trading in weapons and drugs.

"They never provided any evidence. This lie cuts very deep," explains Yasser - who says his brother was still trying to appeal his conviction when the authorities executed him and the 80 other men.

"Not only did they take their lives, they intentionally maligned them and accused them of things they've not done."

After rising to power, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, Saudi's de-facto ruler, promised to modernise the Kingdom - and suggested in an interview in 2018, external that his country, a key Western ally, was trying to "minimise" its use of the death penalty.

But, nearly five years on, Saudi Arabia remains one of the world's most prolific executioners - despite a lull that coincided with Saudi Arabia's presidency of the G20 and the start of the Covid pandemic.

The crown prince - known as MBS - has "done the exact opposite of what he promised" Reprieve's director, Maya Foa, tells me from her east London office. "He has overseen vast numbers of executions and a brutal crackdown on people attending pro-democracy protests."

What's more, she adds, there is a regime of secrecy around the death penalty, explaining that for many of the cases Reprieve have looked at, nobody knew they were even on death row.

"Their family members did not know. So you had people who were arrested, tried, sentenced to death and then executed in secret."

Some families only discovered via social media that their loved ones had been killed, says Ms Foa - describing that lack of official information as one of the "most cruel and distressing" aspects of each case.

Traditionally, beheading has been the main method of execution in Saudi Arabia - the executions used to take place in public - with the names of those killed, and the charges they faced, published on government websites.

But human rights activists say the use of the death penalty has become much more opaque.

Nobody I spoke to knew exactly how executions are now carried out, though firing squads are also thought to be used.

The death penalty is part of a Saudi legal system which "is unfair in its essence", says Ali Adubisi, director of the Berlin-based European Saudi Organisation for Human Rights. "No type of independent civil society or human rights groups can operate there. If we weren't drawing attention to the executions, people would be killed in silence."

Human Rights Watch said that 41 of the 81 men executed in March were from the Shia minority and that "rampant and systemic abuses, external in Saudi Arabia's criminal justice system suggest it is highly unlikely that any of the men received a fair trial". They also heard reports of torture.

When Yasser was first allowed to visit Mustafa, 12 months after his arrest in 2014, he was shocked by what he saw.

"Even though it had been a year since we had last seen him, he couldn't even stand up to greet us.

"He'd fall over as soon as he tried - and when we asked him, he said it was because of torture.

"We saw bruises on his body and he told us he'd been given electric shocks."

The sister of another detainee told me her brother had also been badly tortured.

"He said he was strung up by his feet and beaten. He never imagined a forced confession would be allowed in his trial," says Zainab Abu Al-Khair, whose brother Hussein has been in prison since 2014.

Hussein - a Jordanian driver working for a wealthy Saudi family - was arrested with drugs in his car on the Jordan-Saudi border. Zainab is certain they were not his.

Speaking from her home in Canada, she explains how Hussein's family have been struggling to make ends meet since his arrest. He has a disabled son and, after he was imprisoned, his 14-year-old daughter was "sold into marriage" in Jordan.

Jordanian national Hussein Abu Al-Khair has been in prison since 2014

Last November, Saudi Arabia ended an unofficial moratorium on the death penalty for drug offences - a move described by the UN Human Rights Office as "deeply regrettable". Within a fortnight, 17 men were executed for such offences, the UN said, external.

In prison, says Zainab, men have since been taken from Hussein's cell never to return.

It has left both Hussein and Zainab terrified. "I can't even talk about him without my heart pounding," she told me.

"I think of him all day and at night, I have bad dreams. The thought they might chop off his head - it's barbarity.

"You can't imagine how hard it is. Sometimes I just sit alone and cry, cry, cry."

Zainab Abu Al-Khair and her family check daily whether her brother Hussein is still alive

Part of the anger she is feeling is directed at other countries for allowing Saudi Arabia "to get away with it".

Last March - four days after the mass execution of 81 men - the then UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson met Mohammed bin Salman to try to persuade him to pump more oil to replace Russian fuel imports. Downing Street said Mr Johnson did raise concerns about Saudi Arabia's ongoing human rights issues.

Since coming to power, MBS has carried out social and economic reforms - including allowing women to drive - but they've been accompanied by intensified political repression.

The latest report from the campaign group Human Rights Watch, external describes Saudi Arabia's human rights record as "deplorable" - a stain on its reputation, which it is busy trying to "launder" through sports and entertainment.

The BBC has sent three emails to the Saudi Human Rights Commission - a Saudi government organisation - asking to speak to an official, but has received no replies.

A statement to the BBC from the Saudi embassy in London noted that many other nations around the world have the death penalty, and that countries have different views about what penalties are appropriate. It said: "As we respect their right to determine their own laws and customs, we hope that others will respect our sovereign right to follow our own judicial and legislative choices."

But the comments failed to address the steep rise in executions under the crown prince, MBS, or the way the death penalty is being used, in contravention of international norms.

The UN Human Rights Office told the BBC it was "deeply concerned about the trend in the use of the death penalty in Saudi Arabia".

"In particular, we are concerned by the increase in the number of death sentences issued and upheld, including against child offenders, and for offences that do not meet the 'most serious crimes' threshold of international law, such as drug-related offences," it said.

For those whose loved ones are in prison, it's a desperately anxious time. Hussein's sister keeps a vigilant eye on the family chat group.

"It's not a life to deal with this stress," she says. "Every morning, every evening, we have to check he's still alive."

Additional reporting by Eleanor Montague