Crisis upon crisis: Why it's hard to get help to Syria after earthquake

- Published

Volunteers prepare graves for earthquake victims in the rebel-held town of Jandaris, Syria, on Friday

A crisis within a crisis within a crisis - such is the blighted landscape of Syria, now reeling in the wake of a crushing earthquake and a decade and more of debilitating war.

The country's seismic shock hasn't broken entrenched conflicts and obstacles which have always obstructed urgent humanitarian action in a country ravaged by war.

But four days after a deadly earthquake struck, there's a small crack which may widen the spaces for urgent humanitarian action.

"It's a good step forward but many more are needed," the UN's humanitarian chief, Martin Griffiths, told the BBC after Syrian state media reported that the Syrian cabinet had given the go-ahead for the delivery of humanitarian aid to all parts of the country.

According to the Sana News Agency, that would include both state-controlled areas as well as those controlled by other groups.

The relief effort would be co-ordinated with the United Nations, the Syrian Arab Red Crescent and the International Committee of the Red Cross, it said.

But the news is also being treated cautiously.

Mr Griffiths stressed the announcement only meant aid could be delivered across Syria's internal front lines - not across the border from neighbouring countries. "We are also urgently seeking approval for additional crossing points to meet the life-saving needs of the people."

At present, there is only approved route into the north-western Syrian province of Idlib, the last rebel-held enclave: through the Bab al-Hawa crossing over the Turkish border.

Vital lifelines like this have to be authorised by the UN Security Council. Russia as well as China have repeatedly used their veto to support the Syrian government's rock-hard rule that mechanisms like this violate its sovereignty.

The UN, among others, has repeatedly urged Syria and its allies to allow aid to flow into northern Syria from another route via Bab al-Salameh on the Turkish border, as well as a crossing from Iraq into the largely Kurdish areas of north-eastern Syria.

This week, Syrian opposition groups announced that they had secured Ankara's approval, for the first time in years, to use corridors at Bab al-Salameh as well as another at al-Rai. Unlike the UN, other non-governmental aid agencies don't require UN Security Council approval.

Watch: How rescuers' videos give glimpse into Syria quake horror

On Thursday, when the first UN relief convoy carrying blankets and other supplies finally rumbled through Bab al-Hawa, the reaction was bittersweet.

It was aid that was scheduled to come before the earthquake struck, lamented Syrian journalist Ibrahim Zeidan, who spoke to us from a town near the border crossing.

This route, badly damaged in Monday's tremors, has long been the only source of sustenance for more than four million Syrians, most of whom rely on handouts to survive.

Most were displaced time and again, from one province to the next, in the early years of this conflict. Now people living with almost nothing have lost even that.

"The most earthquake-stricken area of Syria is in the north-west," underlined Jan Egeland, Secretary General of the Norwegian Refugee Council. "We need full and free access across front lines, and full and free distribution."

Aid sources point out that in the past, some humanitarian aid reaching opposition-held areas through government-controlled provinces was rejected. There's also been a concern that aid could be diverted on the way.

"We hope both the armed opposition and the government will put aside politics," Mr Egeland emphasised to the BBC, adding that what was really needed now was a humanitarian ceasefire.

He also expressed caution over the Syrian government's apparent concession, saying similar statements had been made before - but not followed through.

The UN is now under mounting pressure to find new ways to override politics and establish new routes as concern mounts over the depth of suffering, as millions shelter in tents or on open ground in freezing winter temperatures.

This weekend, Mr Griffiths will travel to both Syria and Turkey "to show solidarity with the people of both countries".

But in Damascus, sovereignty will also be on the agenda again especially since Syrian government-controlled areas like the northern city of Aleppo were also hit by tremors - which don't take sides in this conflict.

Syrians, wherever they live, have been pulled down by years of grinding poverty and multiple privations.

"Why don't [Western nations] treat countries the same way?" Dr Bouthaina Shaaban, special adviser to Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, demanded on the BBC's Newshour programme this week.

"It's not humanity, it's politics," she declared, as she called on Western countries to lift sanctions she said were stopping Syrians abroad from rallying to help.

Washington has issued a license to allow sanctions relief for earthquake-stricken Syria.

But its verbal barbs were as sharp as those coming from Damascus. "This is a regime that has never shown any inclination to put the welfare, the well-being, the interests of its people first," said state department spokesman Ned Price.

Aid has always been weaponised in Syria. During our regular reporting from Syria during the most ferocious years of fighting, we saw close up how a merciless "surrender or starve" tactic was repeatedly wielded, mainly by government forces as they cut off entire communities seen as supporting their rivals.

Syrian officials emphasise that aid must be channelled through them, not organisations like the White Helmets.

The volunteer teams trained on pulling survivors from the rubble of Syrian or Russian air strikes have now been rescuing people from the ruins in Idlib.

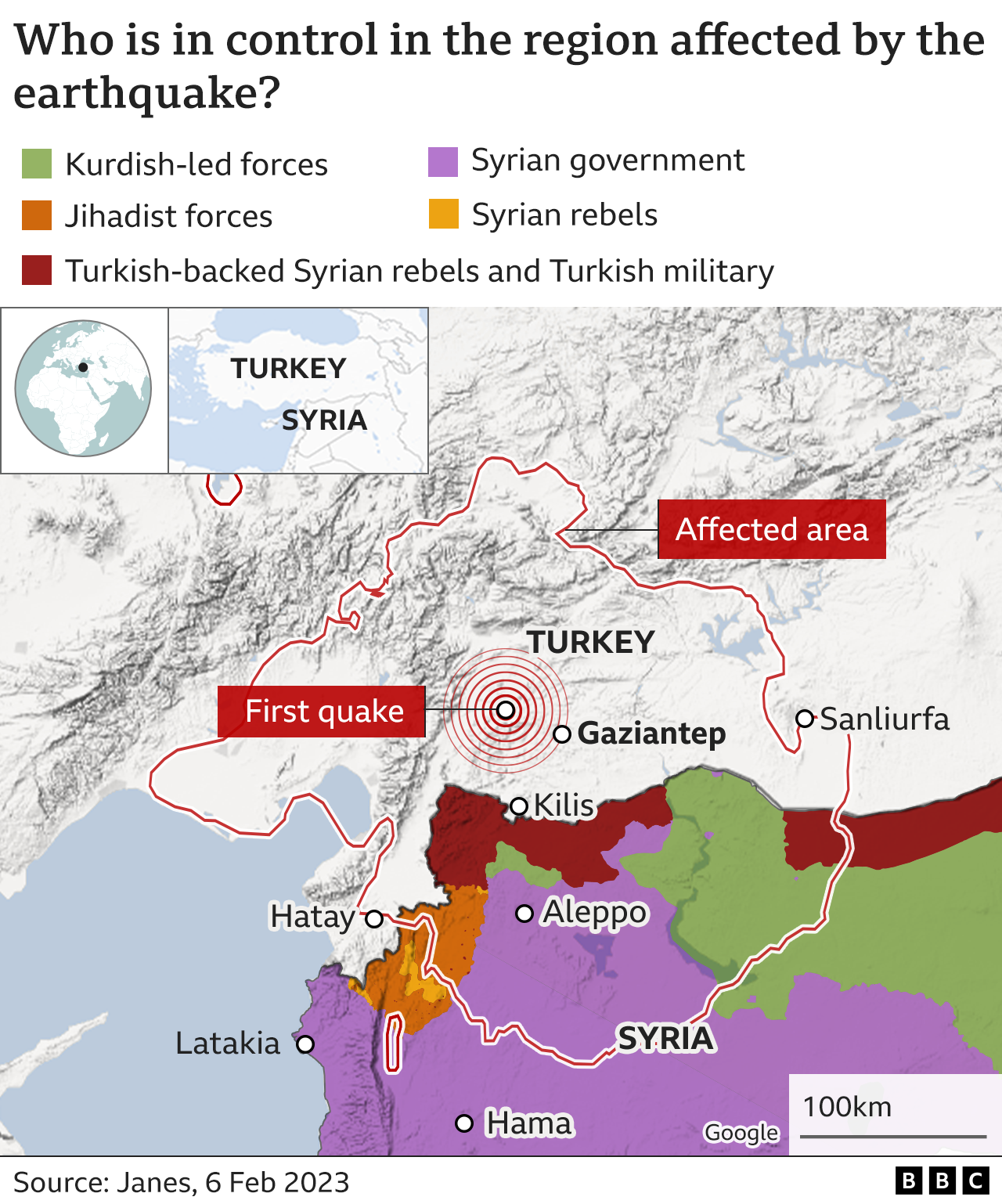

Much of north-western Syria is under the sway of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, an Islamist movement designated as a terrorist organisation by Ankara and Washington, which tries to distance itself from past links to al-Qaeda.

Syria's political map is a minefield for humanitarian work. In the north-west of Syria, it's Syrian Kurdish forces which control large swathes of territory, mainly in opposition to Damascus, but occasionally striking alliances of convenience.

Pockets controlled by Islamic State forces further compound the risks embedded in any relief operation.

Earthquake aid is also reflecting a new regional political map emerging in recent years, as some Arab states - who once worked closely with Western capitals to support the Syrian opposition - have taken a different tack.

The United Arab Emirates, the first among Gulf Arab states to try to draw Damascus back into the Arab fold, partly to try to pull it from its close links to Iran, was quick to establish a humanitarian air bridge to both Syria and Turkey.

Saudi Arabia has done the same, with other Arab states providing aid to either Syria or Turkey, or both.

In recent months, before this latest crisis, there were also signs of a cautious rapprochement between Damascus and Ankara, which have been at daggers drawn throughout Syria's long war.

In December, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, partly nudged by Russia, spoke of "pouring oil on troubled waters".

But the presence of Turkish troops in northern Syria is a major irritant. For President Erdogan, they've been a bulwark against the advance of the Syrian military in the north-east, and Syrian Kurdish forces in the north-west seen as linked to his sworn enemy, the PKK.

Syria, like a territorial version of Russia's traditional nesting dolls, is many wars in one. Turkey, the US, Russia, and Iran all have forces somewhere on the ground, and Israeli warplanes are often in the air against suspected Iranian or Lebanese Hezbollah targets.

Aid should not go through "any of the political actors in Syria, neither in the government-controlled nor in the opposition-controlled areas," said Mr Egeland.

His call to "put people first" is being desperately echoed in areas now levelled by nature's force.

- Published10 February 2023

- Published9 February 2023

- Published9 February 2023