Are Iranian schoolgirls being poisoned by toxic gas?

- Published

More than 1,000 Iranian students - mostly schoolgirls - have fallen ill over the past three months in what has been reported to be a wave of poisonings, possibly with toxic gas. What is making people sick?

Dozens of girls in at least 26 schools across the country reportedly fell ill on Wednesday - a clear escalation in cases.

Many patients have reported similar symptoms: respiratory problems, nausea, dizziness and fatigue.

So what could be behind all these reports - and how have they spread across the country?

The first case

The first known case was reported at a school in the city of Qom, when 18 schoolgirls fell ill and were taken to hospital on 30 November. Since then, at least 58 schools in eight provinces have been affected, according to local media.

Most cases have been at girls' schools. There have also been some reports of teachers and schoolboys affected, along with parents who have arrived at the scene.

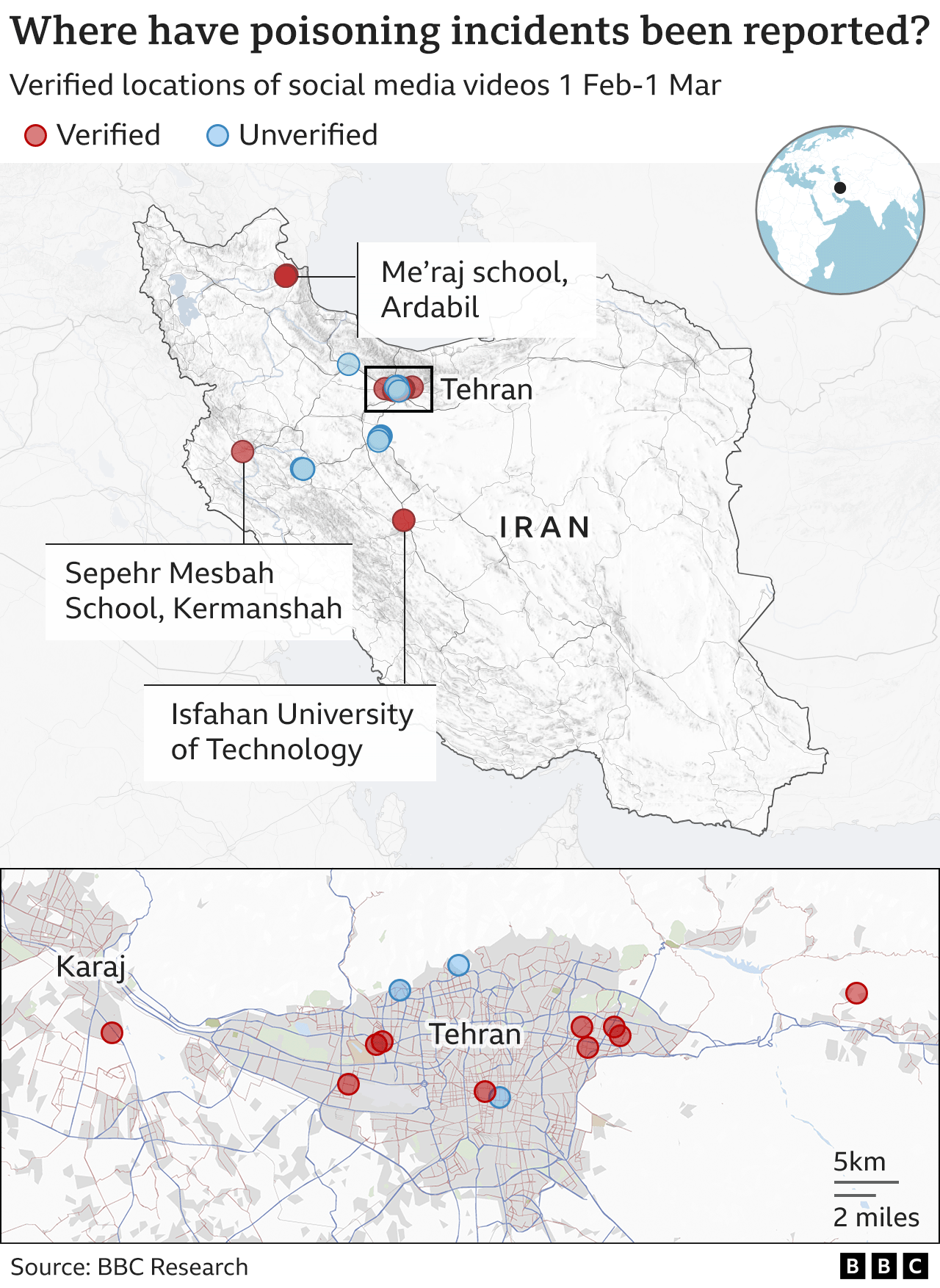

The BBC has analysed dozens of videos posted to social media and has verified many of the school locations filmed.

Many of these show young people in distress in school settings, with some being loaded into ambulances and others lying in hospital beds. Others show ambulances arriving and crowds gathered outside school gates.

One pupil at a school in Shahryar, near Tehran, said she and her classmates smelled "something very strange". It was "so unpleasant, like rotten fruit but much more pungent," she told BBC Persian.

The following day "many of the students fell ill and didn't come to school, our English literature teacher also fell ill," she said.

"When I went home, I was feeling dizzy and sick, my mum was worried cause I was so pale and out of breath."

"Fortunately I recovered soon," she said. "Most of the kids in our school recovered in 24 hours."

She said the school's headmistress and principals were "scared", adding that after reports of cases at other schools surfaced they "came and told us students to not talk about what had happened".

Finding a cause

Government officials have given conflicting reasons for the pupils' illness and Iran's President, Ebrahim Raisi, has ordered an inquiry to get to the "root cause".

Many in Iran believe students are being deliberately poisoned in an attempt to close girls' schools, which have been one of the centres of anti-government protests since September.

In Iran, almost all schools are single sex.

Some pupils and parents suggested that schoolgirls may have been targeted for taking part in recent anti-government protests.

But the cause of illness remains unclear.

Chemical weapons expert Dan Kaszeta, an associate fellow at the Royal United Services Institute (Rusi), said that "finding the alleged causative substance is often the only useful evidence, but can be extremely difficult".

As substances can dissipate or degrade, collecting a sample "pretty much requires you to be there, with the right equipment, at the time of exposure," he tweeted.

Many witness accounts from Iran have focused on smells - describing a tangerine or rotten fish odour - but this can be misleading, he said.

"The various odours described in the Iranian incidents are difficult to tie to particular chemical hazards," he said.

In some videos, girls can be heard complaining about tear gas, which has been widely used during recent anti-government protests. Mr Kaszeta said that was "plausible in some way", as poorly-made tear gas can release off "a lot of junk" with a range of odours.

Mr Kaszeta said biomedical tests - like blood and urine screening - could provide an answer, but were complicated by the number of possible culprits.

"The list of things that are plausibly nasty and irritating enough to make people sick runs into the hundreds of thousands of chemical compounds," he said.

The incidents in Iran have similarities with a series of alleged poisoning cases in Afghan schools in the 2010s, according to Mr Kaszeta. These, he said, were not properly investigated and so remain largely unresolved.

Schoolgirls with symptoms have shared photos online after blood samples were taken

Alastair Hay, a professor of environmental toxicology at the University of Leeds, has reviewed the results of blood tests from some of the Iranian schoolgirls, but said no toxins had been detected. He said he was sent these results unofficially from sources in Iran.

"It's difficult to rule anything in or out at this point as that would require a full screening for a whole variety of things," said Prof Hay, who has investigated suspected chemical attacks across the world.

However, he said, from what he had seen, it was unlikely that a nerve agent or an organophosphate poison - like those used in pesticides - could be responsible.

"What's significant about these cases is that people generally recovered quite quickly," he said. In contrast, in many poisonings, victims are "ill for quite some time," he said.

There have, however, been reports of longer term effects. BBC Persian has spoken to the family of a girl who was unable to walk for over a week, describing her lower body as 'paralysed'. Other similar cases have also been reported to the BBC.

Prof Hay said investigators should take a "very systematic" approach and conduct thorough interviews with all patients, as well as carrying out blood and urine tests.

A psychological source?

While not ruling out a possible toxic substance, both Prof Hay and Mr Kaszeta suggested psychological factors could play a part.

Prof Simon Wessely, a psychiatrist and epidemiologist at King's College London, said several "key epidemiological factors" led him to believe these were not a chain of poisonings, but were instead a case of "mass sociogenic illness" - in which symptoms spread among a group with no obvious biomedical cause.

The spread of cases across the country and the fact it has been predominantly affecting schoolgirls, with fewer boys and adults falling ill, were central to his conclusion, he said. The nature of the symptoms and the fact most patients quickly recovered were also key, he said.

Emergency services attended to reported poisoning cases at a primary school in east Tehran

In cases of mass sociogenic illness, the symptoms experienced are real, but they are caused by anxiety, not toxic poisoning, Prof Wessely said.

"The early stages of poisoning by most things are pretty similar, your pulse starts to race, you feel faint, you go pale, you get butterflies in your stomach, you feel shaky." These symptoms could be from an infection, poisoning or a mass anxiety, he said.

Against a backdrop of harsh government repression of protest, Prof Wessely said it was "not at all surprising that you would get this happening now in Iranian schools".

The Iranian cases appeared to be "very reminiscent" of outbreaks of undiagnosed illness in Kosovo in 1990 and the occupied West Bank in 1986, he said. No biomedical cause was found in either and experts believe they were the result of mass sociogenic illness, Prof Wessely said.

Rusi's Mr Kaszeta, said: "We have to accept the distinct possibility that we will not know what happened or that, actually, multiple different things happened and we're muddling them up together."

Reporting by Shayan Sardarizadeh, Niko Kelbakiani, William McLennan, Jana Tauschinski, Joshua Cheetham and Kayleen Devlin

Clarification 6 March 2023: This article has been amended to remove a term for mass sociogenic illness that has the potential to cause offence. Details of reports of longer term effects have also been added. In addition, the beginning of the piece has been edited to emphasise the fact that most of the reported cases were at girls' schools.

Related topics

- Published28 February 2023