Israel's settlers change West Bank landscape with hilltop outposts

- Published

More than 140 settler outposts have been set up without Israeli government approval since the 1990s

One thing - perhaps the only thing - is beyond dispute. That this is a stunning landscape, particularly now, deep into spring.

The rocky hillsides of this central belt of the occupied West Bank are washed in green. The roads wind and dip. The views can extend, on clear days like these, eastwards all the way to the bare mountains that mark the Jordan Valley.

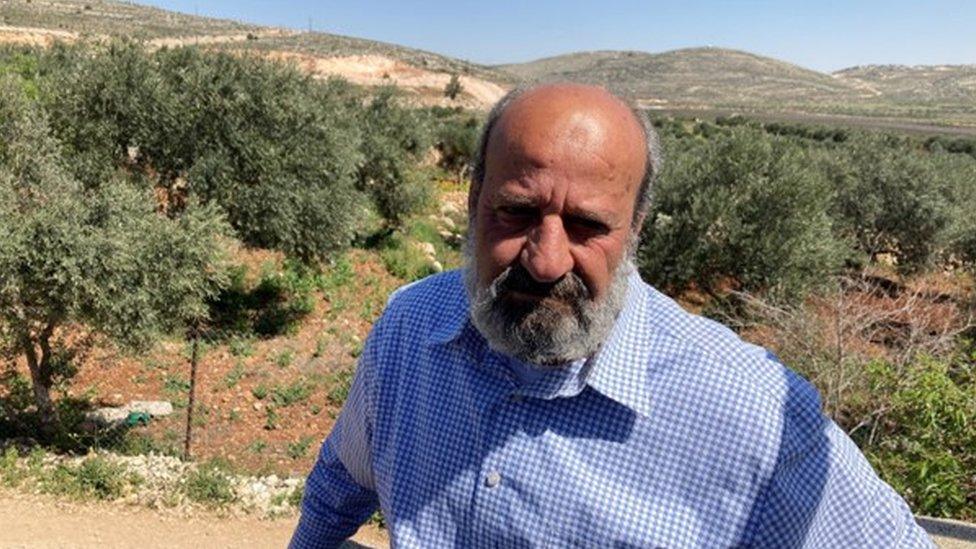

But this ancient hillscape is also changing. You can see how from Abu Khaled's tumbledown farmhouse, a bumpy few minutes' drive from the Palestinian village of Turmus Ayya.

The 65-year-old says he has lived here for more than 50 years. On the ridge of hilltops around him, there's now a string of Israeli settlements.

Abu Khaled, a Palestinian farmer, says settlers want him out of the way

These are widely viewed as illegal under international law, and all but one of the communities now spread across the skyline have up to this point even been considered illegal under Israeli law, as unauthorised "outposts".

And the settlers, says Abu Khaled, want more. They want him out of the way. He shows me some of the recent vandalism - windows smashed, solar panels ripped by rocks, vehicles battered.

"Every night," he says, "I don't sleep from seven in the evening until seven in the morning. Our kids - my grandchildren - they don't sleep. They're afraid the whole time."

Abu Khaled says settlers have attacked his home and smashed its windows

This is part of the patchwork of the West Bank which is supposed, at the moment, to be under the full control of the Israeli security forces. But the refrain from all the Palestinians we meet is that Israeli soldiers only protect the settlers, even those they can see are out to cause trouble.

And the Palestinian Authority, under President Mahmoud Abbas, is held in growing contempt. No-one outside an official position appears to have a good word for them.

Indeed, for the first time, an opinion survey run by the respected Ramallah-based pollster Khalid Shikaki has suggested that a slim majority of Palestinians think they would be better off without the PA offering the pretence of governance.

Even in relatively well-heeled Turmus Ayya, where, according to town councillor Nusseiba al-Niswan, "80% of the residents have US citizenship", people tell you that they think a third intifada - another major armed uprising - is inevitable.

Muhanad* is a 31-year-old who spent months in Israeli military prison as a teenager, picked up for rock-throwing. He said that he and all his friends were now ready to resort to arms.

"No-one protects us here. Every Palestinian who has a gun has a right to defend himself. And almost everyone does have a gun."

But there are limits, Muhanad says. He would not support attacks on Israelis on the land controlled by Israel before the Middle East war of 1967. "But the settlers? They are our enemy."

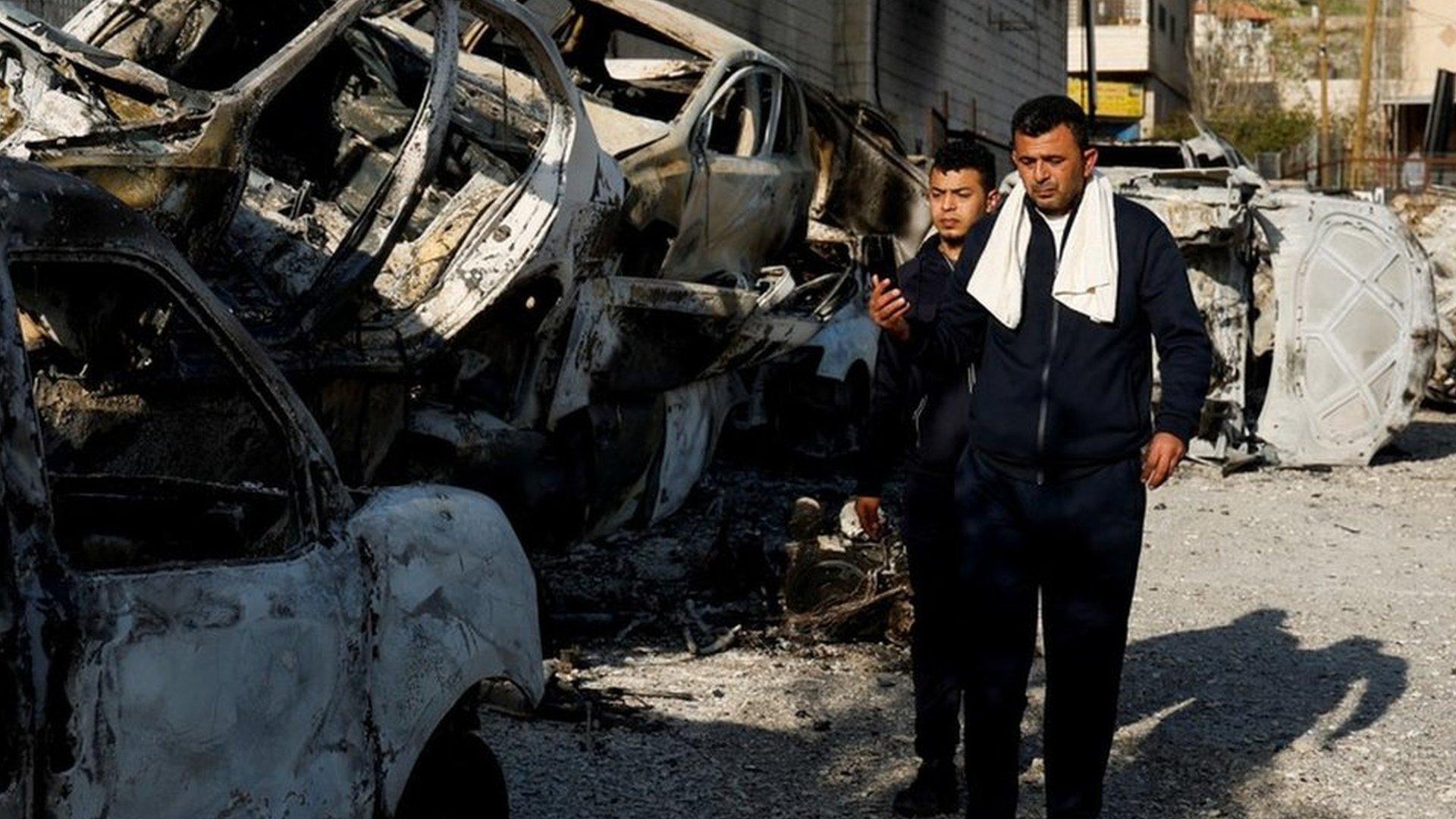

Clashes between Israeli settlers and Palestinians are growing more frequent

Yisrael Medad is one of the original settlers. He has lived in Shiloh, a few kilometres from Turmus Ayya, for more than 40 years.

He has a broad grin, an easy manner, and - at least in English - the drawn-out vowels of an accent bred in Queen's, New York City. Shiloh is the size of a small town, with mature gardens, a supermarket and a bus service.

On a bench overlooking the great sweep of the valley, Yisrael, now in his mid-70s, says he absolutely disapproves of the violence of the "hilltop youth". "It's wrong, and it doesn't help us," he explains. But he has an important qualification.

"There is no such thing as Jewish violence, by itself," he says. "If there was no Arab terror, if there were no Arab incursions, there wouldn't be the response from the Jews - the irresponsible, the illegal response of the Jews."

He says he wishes those youngsters would listen more to the older generation. "But, I have to say, if the world is going to champion the Palestinians on the back of all their terror, as some charities across Europe do, I think they can at least tolerate and understand acts of violence by a small number of Jewish youth."

Last month, two brothers from a settlement in the northern West Bank were killed by a Palestinian gunman

From our vantage point, Yisrael points out the line of outposts - the smaller, not officially sanctioned settlements - which form the "Shiloh bloc", and which aim to bisect the West Bank west to east.

These outposts have the reputation for harbouring harder-line sentiment. They contain the younger, even more ideologically motivated settlers, who are willing to live, at least to begin with, in mobile homes, with few amenities.

Adei Ad may not be an official Israeli settlement. But it has put down roots over the last 25 years. More than 50 families now live there.

Rahel*, a mother of five, works as a local tour guide: the area is rich in biblical history. We speak on the terrace of the small guesthouse she rents to visitors. They come, she says, from all over Israel, and even from abroad.

She greets us with a plate of freshly baked chocolate brownies. Her chalet is a beguiling place, from the bedroom with its own jacuzzi, to the small garden with the views over the vineyards, olive groves and blueberry fields that the settlers have planted.

Rahel says the outposts have given local Palestinians "a better life", including infrastructure improvements

Rahel says life is "much nicer and easier" than it was when she first arrived 18 years ago. Even before this latest Israeli government took power - a governing coalition which is the most nationalist and religious in Israel's history - "this place has been starting to be legalised and developed," she adds.

And she says the benefits have been felt even by those who want her community gone - the Palestinians in their villages further down the hillsides. "I think our Arab neighbours understand they have a better life," she says. "They've got electricity and water and roads, which they didn't have before."

"Adei Ad" means "Forever and Ever" in Hebrew. A short drive north lies an outpost with an equally spiritual name, but one that perhaps speaks to its tougher character.

The view from Esh Kodesh, looking eastwards towards the Jordan Valley

"Esh Kodesh", which means "Holy Fire", is where a willowy young man called Moshe Oref has lived for the past two and a half years.

He came from Jerusalem. The attraction has been two-fold. His commitment, he says, to live in this part of the biblical Land of Israel. It is also, he concedes, a lot cheaper to live out here. "But I pay the price in security. I sleep with a gun under my pillow."

Moshe ranges expansively, as he explains the right of the Jewish people to settle this land, drawing on the Bible, and - less predictably - Oscar Wilde.

He swats away the outside world's consensus on the legal status of the West Bank as occupied territory: "It's absurd."

It's wrong, he argues, to taint several hundred thousand settlers with the actions of "a few dozen young men". You wouldn't judge the whole of Chicago, he says, because of a bunch of gang members.

And yet Moshe also gestures at the nearby Palestinian village of Jalud. "It doesn't work to talk to the Arabs in a Western language. They have their own codes for how they behave. We are in the Middle East. We have to behave the same."

A dented, white four-wheel drive has chugged to a halt next to us. Out clambers the man who runs security for Esh Kodesh and the surrounding outposts. Meir Ayash has a toothy grin and an M16 rifle slung over his shoulder.

His job description is simple, he says. "We prevent terrorists getting in."

Meir Ayash welcomes the presence of ultra-nationalist settlers in Israel's new governing coalition

As to the testimony and evidence of attacks on Palestinian communities, Meir insists: "We don't have any problems with any particular Mohammed this or that. We respect everyone. We are all human beings and neighbours. We are decent and moral."

There is a caveat. "But after the Arabs come and harass and burn and do bad things, people here can lose their patience and go and take revenge."

Meir sees an upside, though. It comes in the form of the new Israeli government and some of the ultranationalist ministers who now have responsibility for administering and policing the West Bank.

"It will be better for the Palestinians," he says, "when they see who's governing this place. They will understand the boundaries. Things will be much clearer for both sides."

* Some names have been changed at the request of the interviewees

- Published21 March 2023

- Published28 February 2023

- Published27 February 2023

- Published20 February 2023

- Published13 February 2023

- Published31 January 2023

- Published18 November 2019