US drone attack: Death of US troops ratchets up pressure on Biden

- Published

The death of three US servicemen and injuring of many others, turns up the heat in an already febrile region and ratchets up the pressure on the US commander-in-chief, President Joe Biden.

This marks the first time American troops have been killed by enemy fire since the Israel-Gaza war erupted.

And it may be the first time during this current crisis that Washington has to take such a hard look at such a difficult decision: where and how should it strike Iran?

Washington will want to send the strongest of messages to Tehran, which it blames for the fires now burning everywhere from Lebanon to Yemen. But it will also want to avoid sparking an even more dangerous escalatory spiral of strikes and counterstrikes.

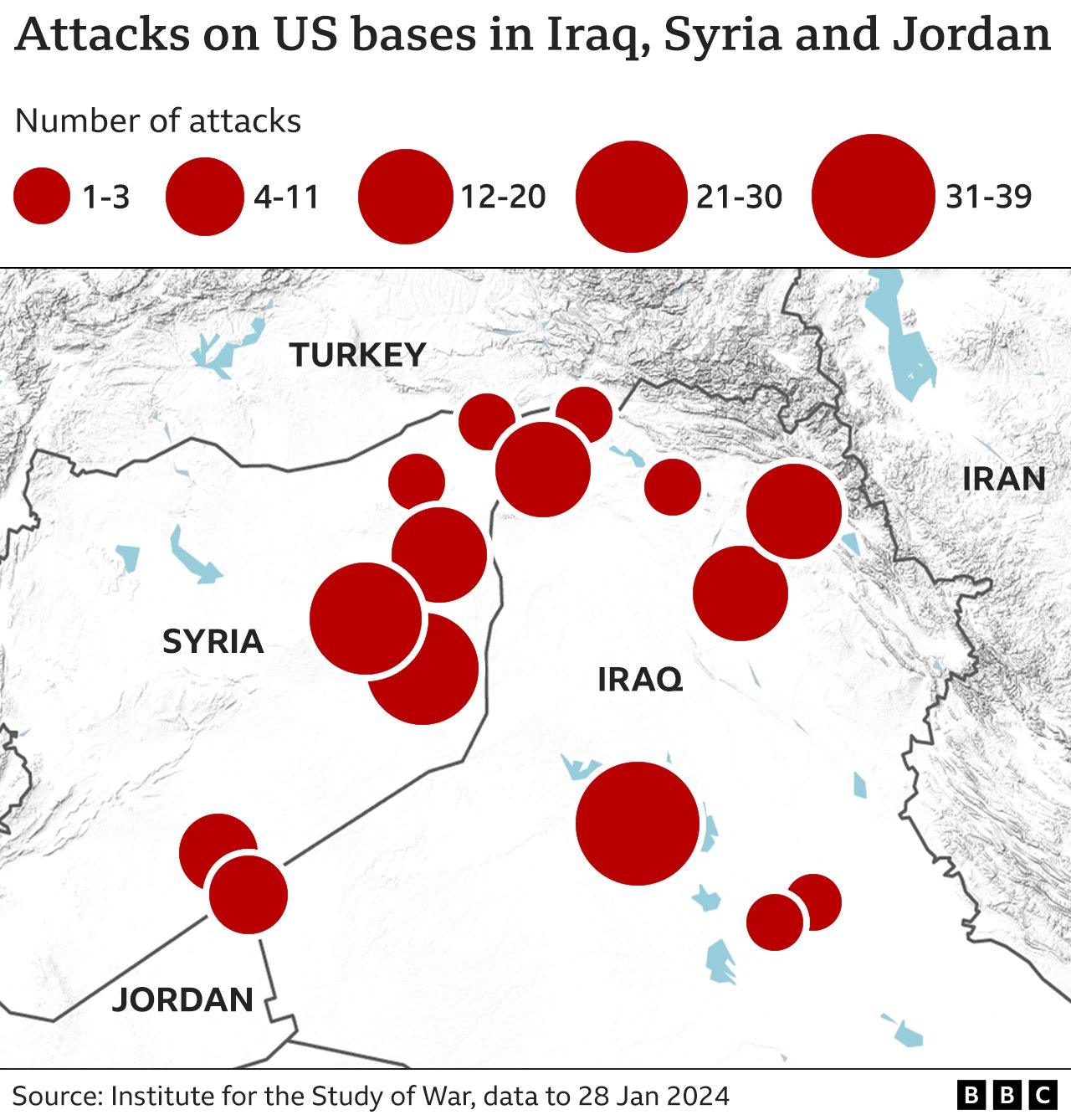

This moment seems to have been all but inevitable. Since mid-October, US military installations in Iraq and Syria have repeatedly come under attack by Iran-backed militias, injuring a growing number of US soldiers. The US has retaliated, at least eight times, by hitting targets in both countries. It was only a matter of time before American lives were lost on this low-intensity, but high-risk, battlefield.

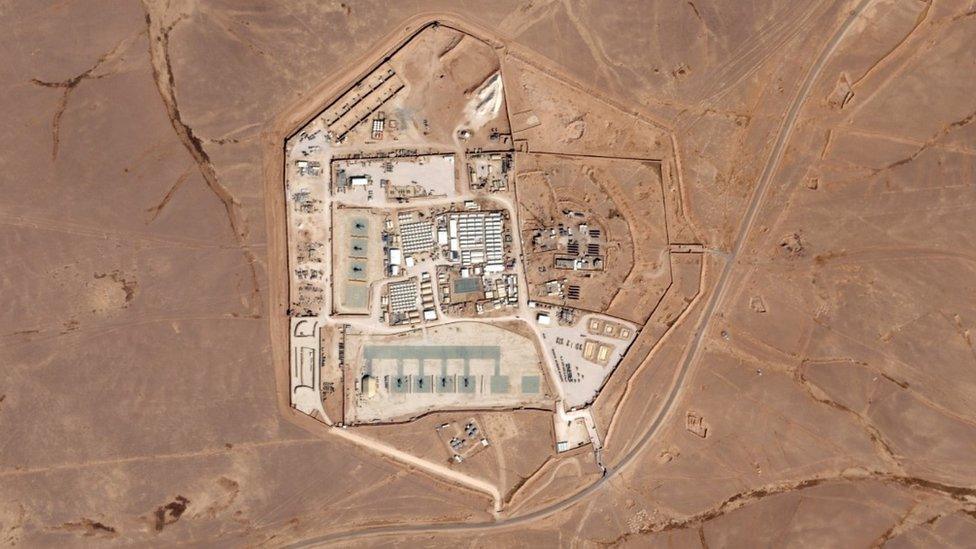

In his first response, President Biden left no doubt where the blame lies this time. The drone attack on Tower 22, a small outpost along Jordan's border with Syria, was the work of "radical Iran-backed militant groups operating in Syria and Iraq."

Iran has shot back, denying any responsibility. Referring to what Tehran calls "resistance groups," a foreign ministry spokesman insisted "they do not take commands (from Iran) in their decisions and actions about how to support Palestine."

Iran's allies across this region have all been trained and armed by its Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) or been instructed on how to arm themselves.

This web of contacts has tightened in recent years in their so-called "axis of resistance" and the Israel-Gaza conflict has visibly strengthened this military alliance of radical non-state actors.

But each actor has its agency, its own agendas and ambitions. In Iraq, most of the assaults appear to have been carried out by groups aligned in the umbrella grouping, named the Islamic Resistance in Iraq. Retaliatory strikes are complicated by the fact that some are also part of Iraq's own armed forces.

In recent months, the US has aimed fire at Iranian assets in the region, including what was described as a training base in Syria and an IRGC weapons depot.

This time, the target will have to be the kind of "high value" one which hurts Iran far more - to prove Washington's mettle in this region, and, just as importantly, at home.

In an election year, President Biden's political adversaries are already exploiting this crisis to reiterate their charge that he is "soft on Iran."

"It's very tricky, very difficult," analyst Fawaz Gerges, Professor of International Relations at the London School of Economics and Political Science told the BBC. "All scenarios have consequences."

In a range of options, striking Iran itself is the riskiest of all. It would be the first attack on Iranian soil since a bungled plot in 1980 to rescue American hostages seized in the wake of the Iranian revolution.

The last highly sensitive US operation against Iran was the assassination four years ago of top IRGC commander Qasem Soleimani, who was cut down by an American drone strike in Baghdad. He was accused of plotting to kill American diplomats and soldiers across the region and had been a pivotal figure in forging this "axis of resistance".

"There has to be deterrent like the Soleimani attack," underlined Joel Rayburn, a former US Special Envoy to Syria, who spoke to the BBC's Newshour programme. "If a cost is not imposed on the Iranian mastermind these attacks will go on and on."

Iran, also under significant pressures at home, has held back in recent months from its own strikes on Israeli or American sites in retaliation for the assassination of several of its senior Revolutionary Guard commanders, which it blames on Israel.

Earlier this month, in its first direct reply, it focused its fire on what was regarded as a "soft target" when it hit what it called a base of Israel's Mossad agency in Iraqi Kurdistan.

The US knows it now has to be seen to be doing something, but even more it has to be seen to succeed.

That's the dilemma for Washington and its allies as the devastating Israel-Gaza war drags on, causing a staggering number of civilian casualties and untold suffering. Iran's allies insist they won't cease fire until there's a ceasefire in Gaza; so far, none is in sight as Israel wages a war it says will only end once Hamas is destroyed and hostages are freed.

Missiles and rockets were fired at the US Al Asad air base last Saturday

Tensions on another front, in the vital shipping lanes of the Red Sea, tell a cautionary tale. The US, backed by the UK and others, already finds itself leading a military campaign against Yemen's Houthis, but it hasn't stopped their attacks on vessels sailing through this passage so pivotal to world trade.

It has only intensified Houthi defiance and catapulted them to the centre of world attention.

A recent Western intelligence estimate put Houthi losses at about 30% of their arsenal. But the Houthis, masters of irregular warfare after surviving nearly a decade of Saudi-led airstrikes, believe they're winning far more than they're losing.

The Houthis, and others in their Iran-backed alliance, have seized on this crisis to try to burnish their reputation as standard bearers for the Palestinians in their battles against Israel. While the Gaza war rages, the US looks set for a long struggle to extinguish multiple fires blazing all at once, and keep them from burning out of control.

Related topics

- Published29 January 2024

- Published24 January 2024

- Published29 January 2024

- Published21 January 2024