The Syria I came back to is not the one I left

- Published

"Yes from the heart" - posters of President Bashar al-Assad are everywhere in government-controlled parts of Syria

BBC Middle East correspondent Lina Sinjab left her home in the Syrian capital Damascus in 2013, soon after the start of the civil war. Recently she was able to travel back for the first time in years, finding a country both very familiar and utterly changed.

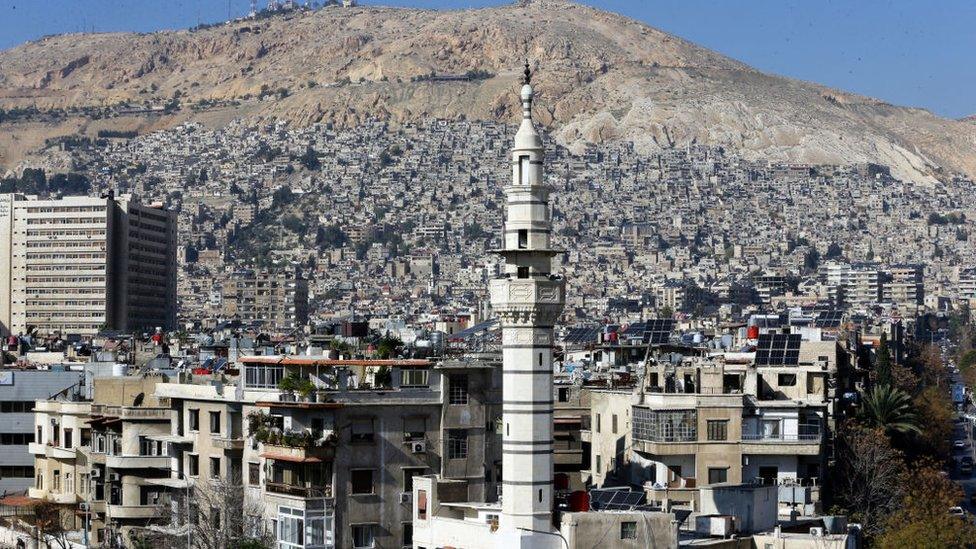

Entering Syria, the scene was as I remembered it - the same mountain, the same oak trees and the same big posters of the president, providing a vivid reminder of who is in charge here.

But few of the people coming in were Syrians. Most were religious tourists from Lebanon and Iraq, though some others may have come to shop in Damascus's souks.

Travelling towards the city, the checkpoints begin. Over the past decade, many people have disappeared here. It is enough to have voiced views critical of the regime, or even to have liked a social media post sympathetic to the opposition.

Almost nothing seems to have changed in President Bashar al-Assad's Syria, yet it is a country transformed by war.

Culture booms as economy collapses

More than a decade after the protests began in Syria, the regime's agenda has shifted. Its main concern today is the economy, not politics.

Arriving in Damascus at night, the city lies in darkness. Even the fanciest neighbourhoods are blacked out. This has been the case for years. Nearly everything is in short supply, forcing Syrians to stand in long queues to secure their basic needs.

You need a smart card with your data on it to get your subsidised bread or allocation of fuel or gas - a text tells you when it's time to join the queue.

The government seems determined to present Syria as a modern state just as everything collapses.

Power cuts are common in Damascus and other cities

It introduced a system for people to pay government bills by bank transfer, via a mobile app. But many don't have access to banks or mobile phones. Another system then emerged that allows you to pay electronically without a bank - but you still need a mobile phone. And sometimes the generators running the telephone masts run out of fuel, and the network drops out.

A whole new generation of Syrians have grown up with war - explosions, bombings and the constant news of death and disappearance. They are indifferent about the war, yet they know that there are boundaries they can't cross in order to remain safe. So they cherish culture, heritage, art and music. Those fields are somehow safe from brutality.

The art and cultural scene is booming, despite everything.

Bands play all types of music, new galleries are opening, and there is a fresh eagerness to explore what's left of Syria's historic sites.

Resentment at Syria's 'occupiers'

The presence of large numbers of people from countries allied to Syria is a cause of anger. Take a walk in the old city and you hear the voices of visitors from Iraq, Lebanon, Iran and even Yemen.

Among them are Shia Muslims brought in by Iran to strengthen its influence in Syria - or as people in Damascus see it, to expand Shia influence in the region. The majority of Syrians are Sunni Muslim and most of the five million refugees who fled the war are Sunni while the ruling elite is mainly Alawite, a Shia offshoot that accounts for about 12% of the population.

Even regime loyalists, who in the past saw Iran's presence as strategic, now call it "occupation". Discontent only increased after Israel reportedly attacked Iranian military and security personnel who stationed themselves in residential neighbourhoods of Damascus. Israel sees the presence in Syria of its arch-enemy Iran as a major threat.

"Our whole building was shaking. Why should I live this with my children? Why do they come and live in residential areas?" one woman asked after an attack on a building in Mezzeh, an affluent area in the south-west of the city.

This week a suspected Israeli air strike flattened the consular section of the Iranian embassy in Mezzeh, killing senior Iranian commanders.

A suspected Israeli air strike destroyed the Iranian consular building in Mezzeh - similar strikes have previously hit residential buildings in the area

The Russians are unwelcome too. Although the number of Russian troops has reportedly fallen since Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine, they are still a visible presence in the country, whether regular Russian soldiers or affiliated fighters from the southern Russian region of Chechnya.

North-west Syria is still controlled by Syrian opposition fighters but many people in Damascus see that part of the country as being ruled by another "occupier", in this case Turkey which has troops there. Meanwhile Kurdish-led forces control most of north-eastern Syria where the country's oil resources are.

Living standards vary in each of these regions, with government-controlled parts of Syria among the poorest of all.

But although President Assad's allies are still influential on the ground, he and his regime are fixing its hopes on another big player.

Syrian elite's Saudi dream

In circles close to the government, Saudi Arabia is described as a great regional player and is no longer seen as fuelling terrorism in Syria, as it did in the early days of the uprising. Some Syrians see Saudi Crown Prince Mohammad Bin Salman as a genius with the potential to set the Arab world on a fresh path.

After years of exclusion from the Arab League, the invitation to Bashar al-Assad to attend a summit in Riyadh last year gave the regime hope that the good old days would soon return. They dream of a stream of cash from Gulf states to rebuild the country and help the bankrupt regime pay salaries.

But right now the country is sinking into poverty and many ordinary people are desperate. "There is no light at end of the tunnel," they say.

It has become normal to see families sleeping in the street and others digging food out of rubbish bins, while in other areas a high-class lifestyle reminiscent of the swankiest parts of London or Paris continues unchanged.

Cafes and restaurants are crowded even as poverty is deepening

The contradictions are stark. Yet at the same time many people who were separated by political disagreements during the war have drawn closer to one another.

The government has become creative in finding ways to extract money from people's pockets through taxes, fines, customs duty and other schemes. Many industrialists choose to close factories or reduce days of work to avoid unexpected fees. Others have been detained and have found that the only way out is to pay the government for the right to do business.

But life goes on and if they can, people get together and socialise over a coffee, a drink or a meal. Late at night, restaurants are packed. Street bars have customers, young and old. Some places play traditional music.

After singing nostalgic songs glorifying the northern city of Aleppo and drinking a few glasses of arak, the local aniseed liquor, a friend contrasted the shaky state of the country with the strength of its culture.

"We will disappear, but the songs will carry our stories and culture for generations to come."