Multi-racial Malaysia caught at economic crossroads

- Published

Kuala Lumpur's Petronas Towers have become a symbol of rapid development - but can Malaysia's rise to prosperity overcome cultural, religious and economic challenges?

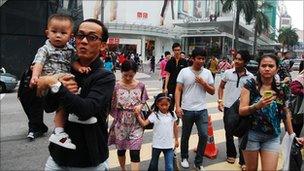

Malaysia is a complex country where race and religion are inextricably linked.

More than half of its 28 million people are Malay and, according to the constitution, must be Muslim.

Ethnic Chinese and Indians have freedom of religion and are mainly Christian, Hindu or Buddhist.

Despite boasts about the country's diversity, there is little interaction between the different races, leading to an escalation of tensions in recent years.

Young Muslims in Malaysia are suffering from an identity crisis, says Amin Rahman from the Young Muslims Project.

The 29-year-old says he grew up bombarded with the message from the government that Malay-Muslims need to protect their own interests from the Chinese and Indians.

That view is now being challenged by a stronger opposition party and easier access to alternative news sources.

"Suddenly we realize that Islam can be more inclusive of other races," Amin tells me.

"It is a lot of re-learning and re-understanding of our principles and our beliefs."

But many scholars say the ethnic divide is entrenched by an affirmative action policy favouring Malays.

Malay priority

Although they make up the majority, Malays are consistently poorer compared to other ethnic groups.

This led to race riots in 1969, where according to official figures nearly two hundred people died and a state of emergency was called.

As an ethnic Chinese, Tony Pua was not allowed into the same elite schools as his Malay friends

To correct this wealth imbalance, the government gives Malays and indigenous groups privileges over ethnic minorities such as cheaper housing and priority allocation of university scholarships and civil service jobs.

The policy has created a new Malay middle class. But after four decades of affirmative action, the average Malay family still earns less than ethnic minorities.

Prime Minister Najib Razak admits the delivery of the policy has been manipulated to benefit only a handful of people.

He has pledged to revamp the scheme but insists affirmative action for Malays needs to stay.

This continues to breed resentment among many Chinese and Indians, who say the policy treats them like second-class citizens.

Tony Pua of the opposition Democratic Action Party says this feeling begins at a young age.

As an ethnic Chinese, he saw Malay classmates who excelled sent off to attend elite schools that were not open to him.

Later, he was rejected for a government scholarship despite achieving grades good enough to study at Oxford University in the UK.

While the government says the number of scholarships they give out corresponds to the ethnic make-up in the country, Tony believes there is sufficient anecdotal evidence that Malays with lower grades are getting scholarships over high-achieving Chinese and Indians.

Aside from the quota system, he says the schools themselves have also been politicised.

"The history books today try to eliminate the influences of any races other than Malays in the founding or building of the country," he says.

But it wasn't always like this. Tony remembers learning about the contribution of all three races in history class as a child.

"That entire chapter has now been reduced to one line," he says.

Ethnic exodus

Ethnic minorities showed their discontent in the 2008 election by largely turning away from the governing Barisan Nasional coalition, denying it a two-thirds majority in parliament for the first time in four decades.

Since then the prime minister has campaigned for unity under the slogan of 1Malaysia.

The message has suffered some setbacks within his party, the United Malays National Organization (UMNO), and among his core Malay-Muslim supporters.

Senior Malay civil servants and teachers have been accused of making derogatory comments about other races, calling ethnic Chinese and Indians "immigrants" despite the fact that many have been settled in the country for generations.

Many ethnic Chinese and Indian Malaysians are voting with their feet to seek fairer policies abroad

UMNO is undergoing a transformation, but it will take time to change the mentality of the party's three million members, says UMNO youth information chief Reezal Merican Naina Merican.

He says the party needs "a new mould of thinking."

"Gone are the days when the government was always right," he says.

Meanwhile, many ethnic minorities are voting with their feet.

In 2010, a World Bank report estimated that around one million Malaysians have left the country. A third of these are well educated and most are Chinese and Indians.

"Discontent with Malaysia's inclusiveness policies is a critical factor," senior economist Philip Schellekens writes.

This outflow of talent casts doubts on whether the country can achieve its goal of becoming a developed nation by 2020.

For now, it is stuck in the middle income level, and losing competitiveness to neighbouring countries in the region.

It is a blow to a country regarded as having one of the most resilient economies in the region after the 1997 Asian financial crisis.

The government has launched an economic transformation programme to more than double the gross national income to $15,000 by 2020.

But there is a sense of frustration among economists like former government adviser Ramon Navaratnam.

"Our racial, religious mix can be a wonderful asset because you have the whole United Nations here," he says.

"Yet we do not know how to maximize or optimise it because of political expediency."

Like many Malaysians, Ramon believes the country will eventually become a high income economy.

It might just take longer than the country's leaders had planned.

Malaysia Direct is a series of reports and articles, online and on TV on BBC World News, which runs until September 4, 2011.