Saving Taiwan's tribal cultures

- Published

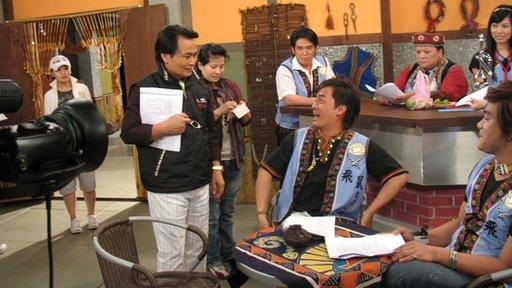

Indigenous tribes have set up a TV station to try to ensure their languages aren't lost

In September, Seediq Bale (Real Men), the first film about Taiwan's indigenous people, opened in theatres across the island.

Long lines of people queued to buy tickets. Local media ran many stories about it and the historical event it was based on during the Japanese occupation. Sales of indigenous arts and crafts items rose. The film is expected to break Taiwanese box office records.

This is the latest sign of Taiwan's increasing interest in the culture of its indigenous tribes.

The island's original inhabitants are of the Austronesian race, connected in language and culture to indigenous people in Southeast Asia, the Pacific Islands, New Zealand and Hawaii.

Mainstream attention

They had lived here for thousands of years before the Han Chinese arrived, but now make up only two per cent of the population.

Their unemployment rate tends to be higher and lifespan shorter than that of the majority Hans.

Partly because of the desire to emphasise a Taiwanese identity separate from China, the government in recent years began promoting indigenous culture, using it to woo tourists and impress official visitors.

At the same time, interest in the island's indigenous cultures is breaking into the mainstream.

But many wonder whether this will actually help Taiwan's 500,000 indigenous people.

Their cultures have been neglected and devastated by harsh policies of assimilation in the past - first by the Japanese and then the Nationalists who took over after losing mainland China to the Communists in 1949. Indigenous people were punished for speaking their languages in schools.

The tribes hope growing tourism will help their cause

The need to make a living has led many to leave tribal villages to work in the cities.

Now, few indigenous people under the age of 40 can speak their tribal language and many do not understand their culture. Unesco has listed several of Taiwan's indigenous languages as "critically endangered".

"Only about 35 per cent of the 14 tribes' people can speak indigenous languages. Only 20 per cent of students in K-12 grade can understand them, and only 10 per cent can speak them," says Chang Shin-liang, head of the language and culture department of the government's Council of Indigenous Peoples.

He and a growing number of people realise the language and cultures are valuable and should be saved.

"Indigenous people's culture is a very important part of Taiwan's original culture," Mr Chang says. "If in the future, we can only see our culture and language in books, then how can we say we're indigenous? Then indigenous people will disappear from Taiwan."

Falling fortunes

At the root of the problem are the issues of land, community and self-rule.

Indigenous people used to be hunters and gatherers or fishermen. Their cultures centered on team work and shared resources, not the accumulation of money and individual profits.

To survive in a changing society, many leased their land to the Han Chinese, often to pay for their children's school tuition or other expenses. The Hans were good at using the land to make money, which led to the tribes' living standards dropping in comparison.

On Taiwan's top tourist attraction Alishan Mountain, for example, most of the land belong to the Tsou tribe, but only a small percentage of the famous Alishan tea is grown by them.

Tourists are taken to the major tourist sites, bypassing the Tsou tribal areas, and few tourists dollars end up benefitting the local people.

As Taiwan's efforts to promote tourism and develop its economy intensify, some of Taiwan's most beautiful and undeveloped mountainous or coastal areas become targets for developers. All too often these are indigenous areas.

That has led to an influx of Han Chinese in areas such as Alishan's Tsou communities, which could further hurt efforts to preserve fading cultures, locals say.

Push for preservation

But things are slowly starting to change. With increased awareness, more young indigenous people are returning from the cities to their ancestral land to start businesses, such as B&Bs, artists' workshops or cafes.

If more people return and succeed in making a living off their land, there is a higher chance communities will be preserved and pass on the culture, experts say.

At the same time, the government and tribal communities have pushed to preserve indigenous traditions.

Schools or government-funded tutorial programmes now teach indigenous children their tribal langauge and customs.

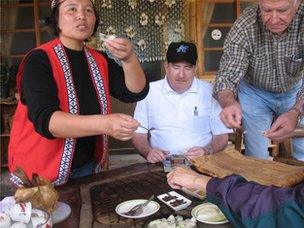

The tribes are trying to save languages and customs before it is too late

"I can speak a little. I hope to be fluent one day," says Lin Yang-min, a Bunun tribe teenager, who learned to sing tribal dialects at a summer camp for indigenous children.

The Tsou tribal village on Alishan, meanwhile, has been holding classes on how to make bows and arrows using traditional methods.

"We use very natural products like bamboo, wood, and bird's feathers. This maintains the traditional culture and passes it on to the next generation," says Tsou community leader, Paicu Luheacana.

'Different feeling'

The tribes are also transcribing their languages - which don't use written text - and using the Roman alphabet, which makes it easier to transliterate.

Indigenous people believe that only with control over their own affairs can they decide how to develop or whether to develop areas that are traditionally theirs.

"We have a different feeling about our land compared to the Han Chinese. We feel because we love this land, we should not hurt this land," Ms Luheacana says. "If we don't do this [achieve autonomy] soon, we'll lose more and more land. We already hear about plans to build a five-star hotel or plans to have a big development project at such and such location.

It's not clear how much public support they will get in a society that has traditionally put development as the top priority, even when it harms the environment.

Many, however, see encouraging signs. Through greater exposure, such as the Seediq Bale, mainstream society has become more aware of indigenous people's issues.

More young people need to learn the old ways before they die out

The film touched many Taiwanese people with its portrayal of the Seediq tribe's uprising against Japanese rule in the 1930s and their brave efforts to protect their land and way of life, even though they were overpowered by the Japanese army.

"I knew of this history, but not the details, because most of the history we learn in school are about the Han Chinese," says Vincent Liao after watching the film. "I feel like I understand them better now."

After centuries of oppression and ignorance of their rights, the changes are being seen as an important first step.

But a lot more needs to be done, says Kolas Yotaka, an anchorwoman at Taiwan Indigenous TV. She says the government should not just give out scholarships or pay for language lessons, but develop local economies, so young people won't have to leave.

"It's a crisis situation," says Ms Kolas.