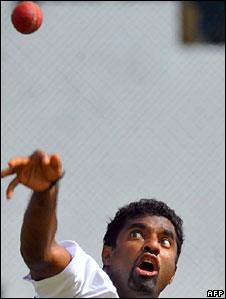

Murali: The man who reinvented spin bowling

- Published

Muttiah Muralitharan may be the greatest spin bowler ever

Muttiah Muralitharan, who played his last Test on Thursday, may have been the greatest bowler to spin a cricket ball. Sports writer Suresh Menon reflects on the career of a remarkable cricketer.

Before the start of the Galle Test, Muttiah Muralitharan's last, India's ace spinner Anil Kumble paid him one of the warmest tributes from one great bowler to another.

"When you see that Murali has played exactly the same number of Tests as me and taken 173 wickets more," he said, "you begin to understand the magnitude of his achievement."

Spin bowling is about masks and disguises, sleights of hand and tempting arcs.

Batsmen reach for the ball that is not there, or adopt a superior air, ignoring the one that seems set to go past but then inexplicably changes course. They are rendered illiterate - unable to read the spinning ball.

Muralitharan's greatness lay in the fact that even when batsmen read him, there was little they could do to keep him out.

Test cricket's most successful bowler is 38, and even if the spirit is willing there is only so much a body can do.

Defining the delivery

Murali's record 800 wickets are likely to stand forever given the diminishing interest in Test cricket, but figures do not tell the full story.

Murali was responsible for cricket's first proper attempt to define the legal delivery.

Thanks to his action, umpires know there is a difference between what the eye sees and the computer calculates.

That he reinvented the art of spin bowling tends to be forgotten in the light of this fundamental contribution.

While studying Murali's action, it was noticed that some of the finest bowlers known for their smooth actions did, in fact, send down illegal deliveries.

By the earlier system - the naked eye - someone like Australian fast-bowler Glenn McGrath was seen as picture perfect. Then technology showed that he too fell outside the demands of the legal.

Muralitharan is a national icon

That led to a new world order where a flexion (the act of bending) of 15 degrees of the bowler's arm was allowed.

Those who criticise him base their observations on the naked eye; those who absolve him go by the definition. Murali's action is legal, but he has suffered more than anyone needs to.

Few cricketers have had to shoulder his burdens - as a minority Tamil in a strife-laden country, as a bowler worshipped and reviled in equal measure, as a player in a team whose fortunes rose or fell according to his performance.

In nearly two decades at the top, he won over everybody - both sides of the ethnic divide and both sides of the bowling-action divide.

His work after the 2004 tsunami in Sri Lanka released him from the narrow confines of a sporting hero and anointed him a national icon. Through it all he has remained rooted, a charmer who finds it hard to believe that by merely doing what he loves the most, he has rewritten the rules of his craft.

Unlike most spinners, Murali didn't appear on the international scene a finished product, every trick in place, every nuance worked out.

It took him 27 Tests to claim 100 wickets; the hundreds thereafter came in 15, 16, 14, 15, 14 and 12 Tests respectively.

This wasn't a genius that was created behind closed doors, but one that evolved out in the open, in front of thousands of spectators.

Symbol

Every ball, every wicket, was tucked away in that remarkable mind; nothing was forgotten, nothing was useless. Muralitharan is the man who remembers everything.

He brought to the craft a new way of doing things, converting a finger-spinning exercise into a wrist-spinning one. He remains the symbol of a resurgent Sri Lanka, a talented side from its pre-Test days but one that needed a touch of iron to perform consistently.

Muralitharan was worshipped and reviled in equal measure

Sri Lanka have won 61 Test matches in all. Muralitharan has played significant roles in 54 of these, claiming 438 wickets at 16.18, taking five-wicket hauls an incredible 41 times.

He might have finished with the best-ever figures for a single innings, but after he had claimed nine wickets against Zimbabwe at Kandy, Russel Arnold dropped a catch at short leg. Then, while bowlers at the other end tried desperately not to take a wicket, Chaminda Vaas accidentally had the last man caught behind amid stifled appeals.

Murali has taken 10 wickets in a match four games in a row. Twice.

That record alone would have ensured Murali a place in the pantheon.

But his influence is not restricted to his country's improved performance.

With better bats, shorter boundaries and tougher physiques, batsmen have threatened to eliminate the offspinner from the game.

Murali has kept the craft alive with a simple ploy - being successful at it. By developing the doosra - a ball which turns the opposite way to a traditional off-break - that was invented by Saqlain Mushtaq, he widened its scope.

He expanded the horizons of the game, bringing in elements that make it more complex, and therefore more interesting, and providing challenges in the meeting of which international batsmen made their reputations.

Nobody bowls like Murali; sadly, not even Murali towards the end, and the time had come. But he will be missed, as any one-of-a-kind performer will be.

There is no "Murali" school of bowling, no successor who bowls in his unique style. Murali stood alone, and now that he is gone, only memories - and video replays - remain.

Suresh Menon is a leading sports writer who is based in Bangalore.