America's secret drone war in Pakistan

- Published

North Waziristan has gained a reputation as having been a haven for the world's most dangerous Islamist militants, Osama Bin Laden among them.

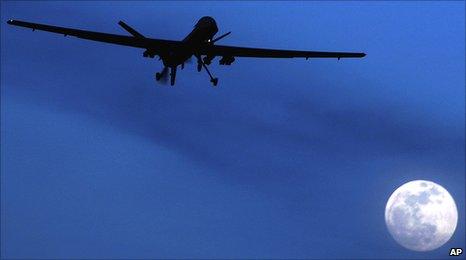

In recent years, with the absence of decisive Pakistani military action in the area, America decided the best way to kill those deemed a risk to US security was by firing missiles at them from unmanned aircraft.

The use of these planes in the tribal areas of Pakistan began under the watch of President George W Bush, but has increased markedly since his successor Barack Obama took office.

The Taliban have admitted, in a statement to the BBC, that they have been affected by the attacks, but say they will win the war in the end.

It is not easy to get an independent assessment of their impact. North Waziristan, where most of the attacks have taken place, is all but inaccessible to foreign journalists.

And those living there are often scared to speak out on the subject.

Raids 'good'

But the BBC has managed to get the views of several civilians living in the battle zone.

One resident, Sher Ahmad Wazir, from Mir Ali in North Waziristan, said: "I'm against the drone attacks because a lot of civilians die. What does America want from us? Our government should not side with the Americans."

But Zahid (not his real name), from Wana, in South Waziristan, said: "I think the drone strikes are good: they target the right people, the terrorists."

Bahar Wazir, from Shawal, North Waziristan, said: "I prefer the drone attacks to army ground operations, because in the operations we get killed and the [Pakistani] army doesn't respect the honour of our men or women."

A major issue with the use of drones concerns civilian deaths.

Often, after drone missile strikes, the Pakistani army will release a statement saying all of the casualties were from the various militant groups based in the area, only for local residents to say civilians have been killed.

It has to be taken into account that those living in North Waziristan may be afraid to admit that militants were killed when the Taliban has such a strong hold there.

Hitting targets?

Recent research by the Ariana Institute in Islamabad found that around 80% of people interviewed in Pakistan's tribal belt felt that targeting by the drone strikes was accurate.

Drone strikes fuel anti-US feeling, but not all Pakistanis oppose such raids

Many said that foreign fighters (Arabs, Uzbeks and Tajiks, among them) in particular were being affected.

Dr Khadim Hussain, director of the institute, says research about whether or not Waziris resented the drone strikes proved inconclusive.

A senior US official has told the BBC that approximately 650 militants have been killed inside Pakistan due to drone strikes since Obama took office.

This official says only about 20 non-combatants have been killed due to those strikes.

Research by the BBC's Urdu service puts the number of those killed considerably higher, and says there have been many cases where there has been no positive identification of those killed at all.

There is little doubt that the onset of drone attacks prompted a change in the pattern of militant behaviour in the tribal areas.

Observers say the Taliban and foreign fighters are more careful about gathering in large groups and tend to move on from locations more quickly.

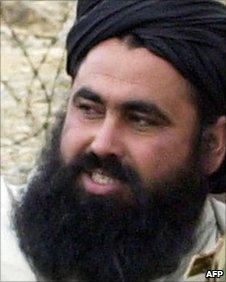

The highest profile casualties of the drone attacks have been one leader of the Pakistani Taliban, another man believed to have been al-Qaeda's third in command, and his successor.

The Taliban admit that the drone attacks have disrupted their operations.

'New blood'

"In the short term, yes, you can say it has caused us some difficulties because of the martyrdoms and realignment of our ranks," says a Taliban spokesman, Muhammed Umer.

"But our command and control system is very strong and well established, so we won't be affected for long," he adds. "Instead we get new courage, becoming more powerful with the flow of new blood."

Certainly, if the measure of success is taken as the number of attacks carried out by the Pakistani Taliban, then the drone strikes have not helped.

The last 12 months have seen an increase in the number of Pakistanis killed in bombings by militants.

Some, like the attack on the Pakistani army's headquarters in Rawalpindi, have shown a new level of audaciousness.

There are many here who feel the drone attacks are being used as a propaganda tool by the militants, and successfully so.

Among them is Rahimullah Yusufzai, a journalist and leading expert on militancy in north-west Pakistan.

"How many people do you want to kill to get Osama Bin Laden?" he asks.

"How many common militants who may not have done much harm to the US or its allies do you want to kill to get Dr [Ayman] al-Zawahiri [Bin Laden's deputy]? That is the question."

Increasingly desperate

But there is a large proportion of Pakistani society which has turned against the influence of militants here.

Militant chief Baitullah Mehsud was a high profile drone 'scalp'

They want to see an end to the kind of bombings that have terrorised them, and they are getting increasingly desperate for a solution.

They are not likely to take to the streets in protest at the drone attacks.

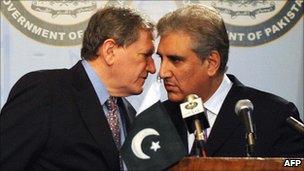

The Pakistani government itself may publicly disapprove of US drone strikes on its soil.

But it rejoiced at the passing of Taliban leader Baitullah Mehsud, who was killed in one such attack in August 2009.

So is Pakistan complicit or not?

Pakistanis will frequently tell you they believe their country's establishment is co-operating with America when it comes to the drone attacks.

It is a charge that has consistently been denied by Islamabad.

I suggested to Pakistani Interior Minister Rehman Malik that even if the planes are controlled in America, some intelligence has to come from Pakistan.

"I am very much fighting the war in that area, I know the way they do it," Mr Malik says. "I know the technology, and I can assure you it is done independently."

He goes further, saying his government has strenuously taken up the issue with Washington as an attack on "our sovereignty".

But many outside observers will see it as convenient for Pakistan to publicly criticise the drones, while privately supporting them.

'Most precise'

The country is often accused by outsiders of allowing militants from Afghanistan to stay in places like North Waziristan.

Pakistan is accused of publicly criticising but secretly supporting US strikes

The critics' theory is that Pakistan feels the Taliban are ultimately going to be back in charge of Afghanistan, and it wants a friendly neighbour over which it can exert its influence.

Those same voices suggest Islamabad wants to deal with some of the militant elements in the tribal areas which are hostile to its interests, but would rather someone else take the blame.

In response to that, the Pakistani army points to the large number of casualties it has suffered in its ranks in the fight against militants.

Is there an alternative?

The CIA declined to comment for this story but the American position is that drones best limit collateral damage.

In speaking to the BBC, a senior US official called it "the most precise weapons system in the history of warfare".

Whether because it does not have the resources, as Islamabad claims, or does not have the will, as many in the West have suggested, the Pakistani army is unlikely to carry out ground operations in North Waziristan.

What Pakistan says it wants is for the drone strikes to continue, but under its ownership, not that of the US.

"The US should just give us the technology," says Rehman Malik. "If we do it ourselves, Pakistanis won't mind."