The sexually abused dancing boys of Afghanistan

- Published

In Afghanistan women are not allowed to dance in public, but boys can be made to dance in women's clothing - and they are often sexually abused.

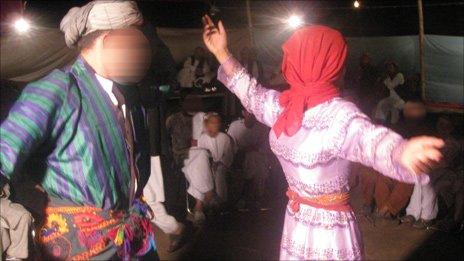

It's after midnight. I'm at a wedding party in a remote village in northern Afghanistan.

There is no sign of the bride or groom, or any women, only men. Some of them are armed, some of them are taking drugs.

Almost everyone's attention is focused on a 15-year-old boy. He's dancing for the crowd in a long and shiny woman's dress, his face covered by a red scarf.

He is wearing fake breasts and bells around his ankles. Someone offers him some US dollars and he grabs them with his teeth.

This is an ancient tradition. People call it bachabaze which literally means "playing with boys".

The most disturbing thing is what happens after the parties. Often the boys are taken to hotels and sexually abused.

The men behind the practice are often wealthy and powerful. Some of them keep several bachas (boys) and use them as status symbols - a display of their riches. The boys, who can be as young as 12, are usually orphans or from very poor families.

Omid's story

I spent months trying to find a bacha who was willing to talk about his experience.

Omid (not his real name) is 15 years old. His father died in the fields, when he stepped on a landmine. As the eldest son, it's his job to look after his mother - who begs on the streets - and two younger brothers.

"I started dancing at wedding parties when I was 10, when my father died," says Omid.

"We were hungry, I had no choice. Sometimes we go to bed on empty stomachs. When I dance at parties I earn about $2 or some pilau rice."

I ask him what happens when people take him to hotels. He bows his head and pauses for a long time before answering.

Omid says he is paid about $2 for the night. Sometimes he is gang raped.

I ask him why he doesn't go to the police for help.

"They are powerful and rich men. The police can't do anything against them."

Omid's mother is in her early 30s, but her hair is white and her face creased. She looks at least 50. She tells me she only has half a kilo of rice and a few onions for dinner. They've run out of cooking oil.

She knows that her son dances at parties but she is more concerned about what they will eat tomorrow. The fact that her son is vulnerable to abuse is far from her mind.

In denial

There have been very few attempts by the authorities to clamp down on the bachabaze tradition.

Muhammad Ibrahim, deputy Police Chief of Jowzjan province, denies that the practice continues.

"We haven't had any cases of bachabaze in the last four-to-five years. It doesn't exist here any more," he says.

"If we find any man practising it we'll punish them."

According to Abdulkhabir Uchqun, an MP from northern Afghanistan, the tradition is not just alive, but steadily growing.

"Unfortunately it is the on the increase in almost every region of Afghanistan. I asked local authorities to act to stop this practice but they don't do anything," he says.

"Our officials are too ashamed to admit that it even exists."

Afghanistan is a country where Islamic values are cherished so I asked a Grand Mullah at the Shrine of Ali in Mazar-e Sharif - the holiest place in Afghanistan - for his views on bachabaze.

"Bachabaze is in no way acceptable in Islam. Actually, it's child abuse. It's happening because our justice system doesn't work.

"This country has been lawless for many years and responsible bodies and people can't protect children," he explains.

Dancing boys are picked out at a young age by men who cruise the streets looking for effeminate boys among the poor and vulnerable. They offer them money and food.

The Independent Human Rights Commission in Kabul is one of the few organisations that has attempted to address the bachabaze practice.

The group's head, Musa Mahmudi, says while it is common in many parts of Afghanistan there have been no studies to determine how many children are abused across the country.

He takes me to the street in front of his office to show me just how difficult it is to protect children here.

The streets of Afghanistan are full of working children. They polish shoes, they beg, they gather plastic bottles to resell. They will take on any job which will earn them some money, he says.

Dancing bells

Every Afghan I spoke to knew about bachabaze. Many tried to convince me that it exists only in remote areas.

But I went to a party late at night in the old quarter of Kabul, less than a mile from the government's headquarters.

It was there that I met Zabi (again not his real name), a 40-year-old man who is proud to have three dancing boys.

"My youngest bacha is 15 and the oldest is 18. It wasn't easy to find them. But if you want it badly - you will find them," he says.

Zabi says he has a good job and he gives them money.

"We have a circle of close friends who also have bachas. Sometimes we gather together and put women's clothes and dancing bells on our bachas and they dance for us for two-to-three hours. That's all."

He says he has never slept with his boys, though he admits he hugs and kisses them.

I tell him that many people think this practice is wrong.

"Some people like dog fighting, some practice cockfighting. Everyone has their hobby, for me, it's bachabaze," he says.

When we leave the party at two in the morning a teenage boy is still dancing and offering drugs to the men around him.

Zabi is not especially wealthy or powerful, yet he has three bachas. There are many people who support this tradition across Afghanistan and many of them are very influential.

The Afghan government is unable and some say unwilling to tackle the problem. They are facing a growing insurgent movement. How long international troops will stay in the country is uncertain.

The justice system is weak, poverty is widespread, and there are thousands of children on the streets trying to make a living.

So bachabaze will continue.

You can hear the entire documentary 'Afghanistan's Dancing Boys' on 8 September from 0905GMT on the BBC World Service, or you can listen online by clicking here. This programme is part of the BBC World Service's World Stories series.

- Published6 September 2010

- Published4 September 2010

- Published31 August 2010

- Published28 August 2010