Floods live on in nightmares of Pakistan children

- Published

Tajjula, seven, was too traumatised to speak when she first arrived at the camp

A small seven-year-old girl in a purple dress is being quietly coaxed into speaking.

She looks up suspiciously at us, the new visitors to the Nowshera Girls' Technical College in Pakistan's Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa province. But she is not a pupil.

Tajjula lives here with her family, along with hundreds of other families who have taken refuge from the floods, crammed into classrooms off a long concrete hall.

She speaks in barely a whisper; I have to bend right down to hear say her name and where she used to live.

"She's much better than she was," Zerena, a social worker explains.

"She didn't speak when she came - we find that with a lot of children. Their parents tell us they are much more fearful of everything now, after the floods, and some don't talk at all."

'Feel lost'

Zerena and her colleagues work with hundreds of children here and even more again at six other camps in the area, with supplies from Unicef.

It is a huge workload for a team of three.

She says that a lot of children feel they have lost their identity.

"The experience of having to leave home quickly and leave their normal lives behind has made them feel lost.

These children have had to leave behind everything they know

"They leave their friends and everything they know behind and they don't fit in anywhere in these busy camps."

It is easy to see how a child could feel lost in a place like this. Small, humid classrooms line dusty corridors. Each room is home to three or four families, jostling for space. There is nowhere to escape, and the noise is constant.

In one of the classrooms, over 100 children squash in to play. It is the only activity there is, and so everyone is excited. Zerena can barely keep control.

They have four skipping ropes between them all, but they have developed a system - one skips and the others clap, sing and jostle to be next. The room is full of smiles.

It is a small window of relief from the long days in the camp, which are by turns monotonous and anxious.

Mohammed Saifullah, another local charity worker, has seen how the cramped living conditions are negatively affecting the 113 families here.

"Certainly we've seen an increase in violence against children," he says.

"Parents are tired and hungry, and under such pressure that they don't have the patience, so they're quicker to discipline their children with force."

'Being brave'

He shows us some games he plays with the children. Having structured play is particularly useful with boys, he says, as they tend not to talk about their experiences for fear of seeming weak.

As well as having to be "brave", very young boys are also expected to be the head of the family in the absence of their fathers, who may have stayed behind to guard what little is left of the family home.

Solveig Routiers, a specialist in child protection in emergency situations with the charity Plan International, says that often a field worker has to take boys aside and work with them individually to try to "break through" the very tough exterior of the ones who are hiding their distress after a very difficult experience.

"It's tough to get through, but even with the toughest children you can eventually find a point where they open up. It takes time, but they are all children at the end of the day," she says.

In such a huge disaster, she adds, resources are inevitably stretched. This sadly means that not all children can receive this kind of attention.

'Everyone was crying'

Ten minutes' drive from the school is Azakhel, an Afghan refugee camp set up 30 years ago which had solidified into a village of brick houses lining dirt streets, a market, and a mosque. The waters here reached 5.5m (18ft). You can still see the water mark on the mosque wall.

When the waters receded, the houses were little more than piles of bricks and kindling.

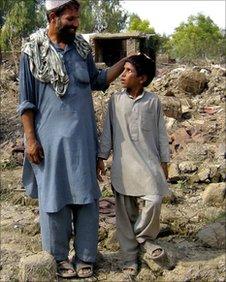

Samar Gul says his son Syed has nightmares about the floods

Eight-year-old Syed Gul has come back to the camp with his father, who wants to see what they will have to do to rebuild. He is a shy and serious child, with big dark circles under his eyes.

Syed's father Samar shudders as he remembers the night the floodwaters rushed in.

"Even the adults were crying when the floods came," he says.

"Now my daughters cry all the time. They are still upset and don't want to come back."

He puts a heavy, rough hand on Syed's head. "Not this one, though - he's brave."

Samar is a dignified man, and describes his neighbourhood slowly and deliberately to illustrate what used to be here. He wants to make it clear to us that they were not living in a camp, or slums.

It takes some time before he admits that his son has recurring nightmares about the water. "He has bad dreams, and can't sleep properly," he says.

"I dream about the water," Syed says quietly, and then will not say any more.