Kashmir's summer of discontent is now an autumn of woe

- Published

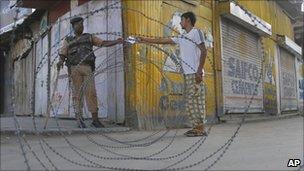

The protests are the biggest security challenge to Indian rule in many years

Continuing unrest in Indian-administered Kashmir is largely due to the failure of successive Indian governments effectively to tackle one of their most pressing domestic problems, argues Sumantra Bose.

Kashmir is on the boil - again. A summer of discontent is yielding to a bitter autumn amid a mounting roster of deaths.

It was not supposed to be this way.

From November to December 2008 people turned out in droves in the Kashmir Valley to choose between pro-India parties competing to form the Jammu and Kashmir regional government.

Respite

Unlike previous elections in 1996 and 2002, Indian security forces did not directly or indirectly pressure people to vote and participation was high in most pro-"azadi" (freedom) strongholds.

Two decades after the insurgency began, hostility and resentment remain

The 2008 election followed four years of declining insurgency in the state.

It steadily declined after 2003, when the Indian and Pakistani militaries agreed a ceasefire on the Line of Control (LoC) dividing Indian- and Pakistan-administered Kashmir.

It meant that the population and the security forces got their first respite since insurgency first gripped the region in 1990.

As Lashkar-e-Taiba - the Pakistan-based group which spearheaded the Kashmir insurgency from 1999 to 2003 - attacked Mumbai, Kashmiris flocked to the polling stations even in notoriously restive areas.

A troubled summer of 2008, which saw rival protest campaigns by Muslims in the Kashmir Valley and Hindus in the Jammu region to the south, blew over by the autumn.

Not so this time. A combination of near-term, medium-term and long-term factors have come together to generate the most severe unrest seen in Kashmir since the early 1990s.

In the near term, the Congress party-led government that has been in power in New Delhi since mid-2004 has aggravated a festering problem by neglecting it.

Lethargy and neglect

Over six years, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh's two governing coalitions have shown no initiative to take forward an opportunity to mend the fraught relationship with the people of the Muslim-majority Kashmir valley.

Kashmir used to be a haven of tranquillity

The lethargy and neglect evident since 2004 stand in contrast to several efforts between 1999 and 2003 by the previous Prime Minister, Atal Behari Vajpayee, to take Kashmir seriously and cautiously reach out to the valley's people.

Delhi's response to the latest turmoil has been a combination of hand-wringing, indecision and the familiar although well-founded claims of Pakistani instigation (the inter-governmental dialogue between India and Pakistan that began in 2004 is virtually defunct).

In fact Delhi's failure to grasp the nettle has been compounded by the indifferent performance of the state government elected at the end of 2008.

The head of that government, Omar Abdullah, is the grandson of Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah, Kashmir's most important political leader from the 1930s until his death in 1982.

Unlike his grandfather, the present incumbent is no man of the masses. He has been out of touch with the grassroots of even his own party, the Jammu and Kashmir National Conference.

'Stone pelters'

The renewed turmoil must be understood in a much longer time-frame, however. The last 20 years have seen the brutalisation of local society, particularly in the Kashmir Valley.

This year there have been almost daily curfews

An entire generation has grown up and come of age in an environment of repression and violence.

This is the generation of "stone-pelters", for whom the stone has replaced the AK-47s wielded by so many of the previous generation during the 1990s.

The defining image of the intifada - or uprising - that erupted in the Palestinian Territories in the late 1980s was that of legions of stone-throwing teenagers.

The stone supplanted the gun as the weapon of protest once the Palestine Liberation Organisation's armed struggle, waged since the late 1960s, reached a dead-end.

Despite the sharp decline of insurgency to near-negligible levels, the Kashmir valley remains a police state.

The new generation are unwilling to put up with such a situation in the absence of the threat posed by insurgency.

The deep sense of oppression and grievance being vented by the stone-pelters goes back 60 years.

Bloodshed

Their grandparents' generation recall the 1950s and 1960s, when popular leaders - most notably Sheikh Abdullah himself - were cast into jail, harsh police methods used to muzzle protest and elections doctored to install Delhi's favoured clients in office.

Delhi and the state government have 'failed to grasp the nettle'

Their parents' generation grew up in the 1970s and 1980s, when any tentative liberalisation of India's Kashmir policy relapsed into draconian control and election-rigging. By the mid-1980s the young generation was already a long way down the path to insurgency.

The experience of several generations over the years has been defined by the bloodshed of the insurgency and the Indian state's response to it.

There are not many families in the valley, or in the insurgency-prone areas of the Jammu region, who have not been affected in some way. In fact, thousands of families have been destroyed.

Stone-pelting is the latest manifestation of an unhealed trauma and an unaddressed political problem.

The Koran controversy in the United States has added further fuel to a combustible mix.

Recent protests triggered by that issue led to deaths in communities outside the core base of "azadi" sentiment - in an area of the valley dominated by the Shia minority and in a Muslim-majority area of the Jammu region.

In the concluding scene of the classic 1966 film The Battle of Algiers, which depicts in riveting style the struggle for Algeria between France and Algerian nationalists, a harried French police officer exhorts a stone-throwing crowd of Algerians over a hand-held loudhailer: "Go home! What do you want?"

After a brief pause, a chorus of voices answers from behind a curtain of tear-gas: "Istiqlal! Istiqlal!" (Independence!).

The Kashmiri equivalent of the French solution in early 1960s Algeria - the withdrawal of Indian troops and Kashmir's independence - is neither viable nor desirable in Indian-administered Kashmir today.

The state of Jammu and Kashmir is diverse, and most of the Jammu region and the entire Ladakh region are not at all involved in the agitation against Indian authority which is gripping the valley.

Yet 20 years after the start of the insurgency, hostility and resentment remain in Kashmir. A fundamental improvement of this poisoned relationship is no easy task, but it must still be attempted.

Sumantra Bose is professor of International and Comparative Politics at the London School of Economics. His books include Kashmir: Roots of Conflict, Paths to Peace (Harvard, 2003), and Contested Lands: Israel-Palestine, Kashmir, Bosnia, Cyprus and Sri Lanka (Harvard, 2007).