Karachi: Volatile metropolis

- Published

A 2002 attack left 11 French engineers dead and others wounded

Karachi, Pakistan's largest city and commercial capital, has a history of violence.

One major cause - sectarian disputes between majority Sunni and minority Shia Muslims - regularly rears its head.

In recent years there has been a spate of shootings, some of them sectarian, which have left many dead. Ethnic divisions are also re-emerging.

In August, at least 80 people were killed in three days of violence after MQM (Muttahida Qaumi Movement) parliamentarian Raza Haider was assassinated in Karachi.

Most of those killed belonged to the Pashtun community, whom leaders of the MQM which represents the Mohajir community had initially held responsible for the attack.

The city has also had its share of militant violence.

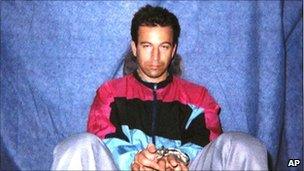

Daniel Pearl in shackles after his kidnapping in Karachi

In 2002, there was a shoot-out between police and suspected al-Qaeda militants; two bomb attacks on foreigners, an alleged militant attempt on the life of then President Pervez Musharraf, and the kidnapping and killing of US journalist Daniel Pearl.

The same year, Yemeni national Ramzi Binalshibh, who claimed to have been one of the organisers of the 9/11 attack on the US, was captured after a three-hour gun battle at an apartment in the city.

And it was to Karachi that a journalist from the Arabic al-Jazeera television network was invited to interview two top al-Qaeda leaders. In February 2010 senior Taliban leader Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar was captured in the city.

The fact that al-Qaeda and Taliban men were in Karachi rather than holed up in a tribal area may surprise some.

But in fact correspondents say militant suspects are probably less conspicuous in Karachi than even among sympathetic tribal groups in the north.

Rivalry

Karachi is a densely populated port city, bursting at the seams. A 1998 census put the population at just under 10 million - but a more realistic figure is probably nearly double that.

Shia-Sunni divisions are a source of frequent tension

The population is multi-ethnic, with about 500,000 new economic migrants arriving in the city every year - not just from the other provinces but also from neighbouring countries like Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Nepal and Sri Lanka.

The city's population is highly diverse - but observers say it is hardly a melting pot. Individuals survive by being a part of a group or mafia that can protect their interests.

In 2007 Karachi was the site of some of Pakistan's worst political violence in years.

The city descended into anarchy as the Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM), an ally of then President Pervez Musharraf, held a rally on the same day as a planned opposition demonstration.

More than 30 people were killed after armed clashes broke out.

The violence was just another reflection of the rivalry between Karachi's different communities - Mohajirs (immigrants from India), Pashtuns from the north-west frontier and Sindhis.

The different groups are bitter ethnic and political foes and tensions have often resulted in bloodshed.

Declining fortunes

At the time of the partition of the sub-continent in 1947, Karachi was a sophisticated trading city inhabited by a large number of affluent Hindus, Parsis, Muslims and Christians.

Two factors started post-partition Karachi off on the wrong footing. One was the controversial choice of the city as Pakistan's federal capital - which effectively cut it off in administrative terms from Sindh province which surrounds it.

The second factor was the arrival of 600,000 refugees from the Muslim areas of India after partition. These Urdu-speaking refugees (Mohajirs) and their subsequent desire to get government and white-collar jobs was much resented by native Sindhis.

Karachi was the federal capital for only 12 years, and when the central government transferred to the Punjab, the city was left with a sense of abandonment.

This sense of exploitation is reflected in the complaint by many of Karachi's inhabitants that the city is the source of 40% of Pakistan's revenues - yet gets very little in return.

It continued as a bustling port and trading centre and economic migration rose, especially by Pashtuns from North-West Frontier Province who made up most of the labour force for the city's construction.

But ethnic differences between Pashtuns and Mohajirs began to emerge. In the 1970s, there were also tensions between Mohajirs and native Sindhis.

By the 1980s, there was a considerable influx of weapons due to the use of Pakistan as a conduit for US arms to Afghanistan. The city's various vested interests became armed and dangerous, resulting in sometimes violent clashes.

'Mafia-style' violence

Municipal planning and development in Karachi has not kept pace with its growth. Since there was insufficient housing available to migrants this resulted in large squatter settlements and slums.

Today, about five million people live in these sorts of dwellings.

Transport is woefully inadequate and water supply and housing problems remain chronic.

As demand for these services outstrips the government's ability to supply them, a lucrative sub-economy has sprung up where everything is available - for a price.

Rival mafias have marked out their turf and consolidated their businesses, often winning over law enforcers and administrators by offering them a slice of the pie.

During the Zia years, local elections were put on hold, so for years Karachi's inhabitants had no local representation, nobody who they could go to and demand action on local issues.

This strengthened people's dependence on special interest groups, whether ethnic or sectarian.

In the past two decades crimes like kidnapping for ransom, car-jacking and armed robbery have shot up.

These crimes are often committed by people with links to various political or religious groups, and are a way for them to raise funds to keep their activities going.

The authorities say Karachi is an extremely difficult city to police, partly because of the constantly changing population - but mainly because of the tangled web of vested interests that operates outside the law.