India to compile 'world's biggest' ID database

- Published

India has launched a huge national identity scheme aimed at cutting fraud and improving access to state benefits.

Using biometric methods, including an iris scan, the system will log details of India's population of more than one billion people on a central database.

It was launched by Prime Minister Manmohan Singh and Congress party leader Sonia Gandhi in western India.

The data will be stored online in what India says will be the biggest such national database in the world.

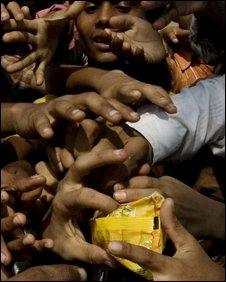

The unique identification (UID) programme will help those in poor, marginalised communities who find it difficult to access public services and benefits because they do not have official records, officials say.

The government expects to give a UID number to every Indian citizen within four years.

Birth registration is not universal and it is hoped that the database will give an accurate picture of Indian society.

'Special moment'

The new ID scheme was launched in the village of Tembhili in Nandurbar district of western Maharashtra state.

The government says better ID will mean benefits are delivered more fairly

The ID numbers were handed out to 10 people, including three children.

The tiny village of 1,500 people was colourfully decorated and the villagers were excited to see Congress chief Sonia Gandhi - who smiled and waved at them - although few locals knew what the scheme was about, the BBC's Prachi Pinglay reports from Tembhili village.

Prime Minister Singh described the start of the process as a "special moment" that would empower the most marginalised in society.

"It will help strengthen the rights of the downtrodden and the poorest, including women," AFP news agency quoted him as saying.

Mrs Gandhi described the launch as a "new beginning" for India.

Billionaire IT expert Nandan Nilekani, who was drafted in by the government to run the project, was also present at the function.

Under the scheme, all Indians will be issued a 12-digit ID number which they will use to receive welfare handouts, to apply for other documents like passports and even to open bank accounts, the BBC's Mark Dummett in Delhi says.

As well as iris scans, photographs, fingerprints and other personal information will be collected and then stored on a vast central database.

The government hopes this will prevent corrupt officials from faking the names of people seeking welfare benefits or access to education - potentially saving billions of dollars.

Critics, however, complain that the project itself will cost billions of dollars and are also worried about the authorities collecting so much personal information.

Others say there is no guarantee that the scheme really will make much of a difference to India's corrupt and inefficient bureaucracy. Some say the focus should be on improving services for the poor, rather than access to them.

- Published29 September 2010