Who are the Taliban?

- Published

Taliban security guards in Kabul, a year on from their triumphant return to power

The Taliban retook control of Afghanistan in 2021, two decades after being removed from power by a US-led military coalition.

The hardline Islamist group advanced rapidly across the country, seizing province after province before taking the capital Kabul on 15 August last year, as the Afghan military collapsed.

Foreign forces, who had agreed to leave, were stunned by the speed of the advance and had to accelerate their exit. Many Western-backed Afghan government leaders fled, while thousands of their compatriots and foreigners fearing Taliban rule scrambled to find room on flights out of the country.

Within weeks, the Taliban were in control of all of Afghanistan - something they had not managed to do in their first stint in power between 1996 and 2001.

The group had struck a deal with the Americans in 2020 for US troops to withdraw, following a bloody but ultimately successful guerrilla campaign lasting many years.

Taliban fighters pictured in Laghman Province last year as they began a lightning offensive to retake the country

Under the deal, the Taliban committed to national peace talks, which never took place, and to preventing al-Qaeda and other militants from operating in areas that the Taliban controlled.

Following the group's return to power, Afghanistan's economy imploded, leaving a huge portion of the population struggling to find enough money to eat and to access other essentials.

Billions of dollars in Afghan assets held abroad are frozen as the international community waits for the Taliban to honour promises still to be met on security, governance and human rights, including allowing all girls to be educated.

Rise to power

The Taliban, or "students" in the Pashto language, emerged in the early 1990s in northern Pakistan following the withdrawal of Soviet troops from Afghanistan.

It is believed that the predominantly Pashtun movement first appeared in religious seminaries - mostly paid for by money from Saudi Arabia - which preached a hardline form of Sunni Islam.

The promise made by the Taliban - in Pashtun areas straddling Pakistan and Afghanistan - was to restore peace and security and enforce their own austere version of Sharia, or Islamic law, once in power.

From south-western Afghanistan, the Taliban quickly extended their influence. In September 1995, they captured the province of Herat, bordering Iran.

Exactly one year later, they captured the Afghan capital, Kabul, overthrowing the regime of President Burhanuddin Rabbani - one of the founding fathers of the Afghan mujahideen that resisted the Soviet occupation. By 1998, the Taliban were in control of almost 90% of Afghanistan.

Afghans, weary of the mujahideen's excesses and infighting after the Soviets were driven out, generally welcomed the Taliban when they first appeared on the scene.

Their early popularity was largely due to their success in stamping out corruption, curbing lawlessness and making the roads and the areas under their control safe for commerce to flourish.

But the Taliban also introduced or supported punishments in line with their strict interpretation of Sharia law - such as public executions of convicted murderers and adulterers, as well as amputations for those found guilty of theft. Men were required to grow beards and women had to wear the all-covering burka.

The Taliban also banned television, music and cinema, and disapproved of girls aged 10 and over going to school. They were accused of various human rights and cultural abuses. One notorious example was in 2001, when the Taliban went ahead with the destruction of the famous Bamiyan Buddha statues in central Afghanistan, despite international outrage.

This time round, there has been no repeat of such excesses, but the Taliban are accused of a range of well-documented abuses, including killing opponents, as well as beating and detaining journalists and Afghans protesting for their rights.

Women are no longer allowed to go on long-distance journeys without a male chaperone and, while not required to wear the burka, have been ordered to cover their faces in public. Most women are not allowed to work.

Taliban gunmen controlling the Kandahar-Herat highway, near Kandahar city, 31 October 2001

Pakistan has repeatedly denied that it was the architect of the Taliban enterprise, but there is little doubt that many Afghans who initially joined the movement were educated in madrassas (religious schools) in Pakistan.

Pakistan was also one of only three countries, along with Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), which recognised the Taliban when they were in power the first time round in Afghanistan. It was also the last country to break diplomatic ties with the group.

At one point, a Pakistani offshoot of the Taliban threatened to destabilise Pakistan from areas it controlled in the north-west. One of the most high-profile and internationally condemned of all Pakistani Taliban attacks took place in October 2012, when schoolgirl Malala Yousafzai was shot on her way home in the town of Mingora.

A major military offensive two years later following the Peshawar school massacre greatly reduced the group's influence in Pakistan, though. At least three key figures of the Pakistani Taliban had been killed in US drone strikes, including the group's leader, Hakimullah Mehsud in 2013.

Schoolgirl and rights activist Malala Yousafzai was shot by Taliban gunmen in October 2012

Al-Qaeda 'sanctuary'

The attention of the world was drawn to the Taliban in Afghanistan in the wake of the 11 September 2001 World Trade Center attacks in New York. The Taliban were accused of providing a sanctuary for the prime suspects, Osama Bin Laden and his al-Qaeda movement.

On 7 October 2001, a US-led military coalition launched attacks in Afghanistan: by the first week of December, the Taliban regime had collapsed. The group's then leader, Mullah Mohammad Omar, and other senior figures, including Bin Laden, evaded capture despite one of the largest manhunts in the world.

Many senior Taliban leaders reportedly took refuge in the Pakistani city of Quetta, from where they guided the Taliban. But the existence of what was dubbed the "Quetta Shura" was denied by Islamabad.

Despite ever higher numbers of foreign troops, the Taliban gradually regained and then extended their influence in Afghanistan, rendering vast tracts of the country insecure, while violence in the country returned to levels not seen since 2001.

There were numerous Taliban attacks on Kabul and in September 2012, the group carried out a high-profile raid on Nato's Camp Bastion base.

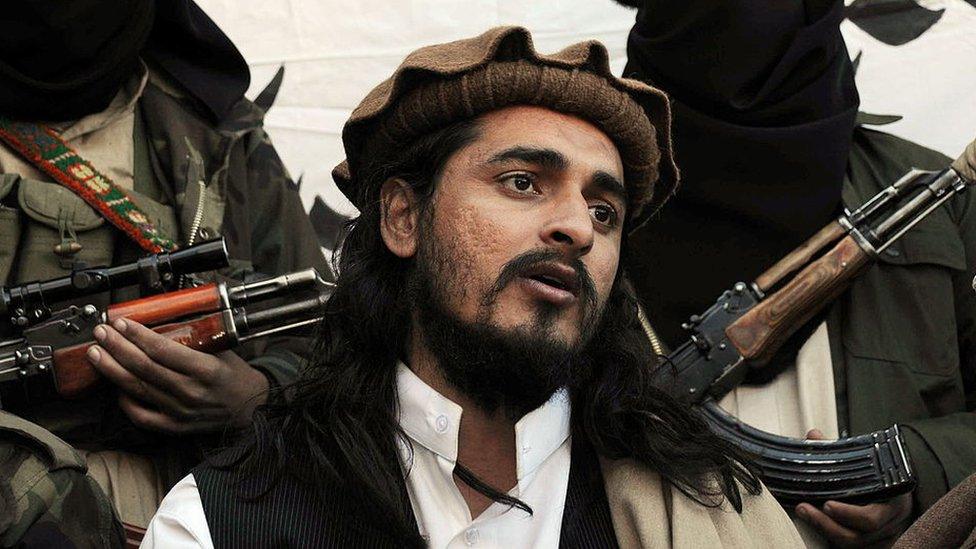

Pakistani Taliban leader Hakimullah Mehsud was killed in a US drone strike in 2013

Hopes of a negotiated peace were raised in 2013, when the Taliban announced plans to open an office in Qatar. But mistrust on all sides remained high and the violence went on.

In August 2015, the Taliban admitted they had covered up Mullah Omar's death - reportedly from health problems at a hospital in Pakistan - for more than two years. The following month, the group said it had put aside weeks of infighting and rallied around a new leader, Mullah Mansour, who had been the deputy of Mullah Omar.

At about the same time, the Taliban seized control of a provincial capital for the first time since their defeat in 2001, taking control of the strategically important city of Kunduz.

Mullah Mansour was killed in a US drone strike in May 2016 and replaced by his deputy Mawlawi Hibatullah Akhundzada, who remains in control of the group.

Seizing power

In the year following the US-Taliban peace deal of February 2020 - which was the culmination of a long spell of direct talks - the Taliban appeared to shift their tactics from complex attacks in cities and on military outposts to a wave of targeted assassinations that terrorised Afghan civilians.

The targets - journalists, judges, peace activists, women in positions of power - suggested that the Taliban had not changed their extremist ideology, only their strategy.

Despite grave concerns from Afghan officials over the government's vulnerability to the Taliban without international support, new US President Joe Biden announced in April 2021 that all American forces would leave the country by 11 September - two decades to the day since the felling of the World Trade Center.

Hibatullah Akhundzada is a religious scholar and he is former head of the Taliban courts

Having outlasted a superpower through two decades of war, the Taliban began seizing vast swathes of territory, before once again toppling a government in Kabul in the wake of a foreign power withdrawing.

They swept across Afghanistan in just 10 days, taking their first provincial capital on 6 August. By 15 August, they were at the gates of Kabul.

Their lightning advance prompted tens of thousands of people to flee their homes, many arriving in the Afghan capital, others heading for neighbouring countries.

The future for Afghans living under the Taliban's rule remains highly uncertain. While most are relieved war is over, millions are struggling to survive.

No country has recognised the Taliban government in the year since they returned to power.

The August 2022 killing in a US drone attack of al-Qaeda's leader Ayman al-Zawahiri in Kabul will do nothing to persuade Taliban critics that the group has turned over a new leaf.

Hardliners in the movement appear to have the upper hand on issues such as female employment, freedom of speech and secondary education for girls, meaning that desperately needed foreign-held funds are unlikely to be released any time soon.

Related topics

- Published14 April 2021

- Published28 February 2021

- Published25 June 2021