Afghanistan hit by disfiguring tropical disease

- Published

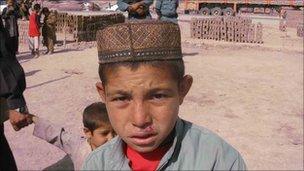

The disease creates sores and child sufferers are often subject to bullying

The Afghan capital, Kabul, has been hit by a disfiguring tropical skin disease, the World Health Organization says.

The WHO warned that the disease, cutaneous leishmaniasis, threatens the health of 13 million Afghans, especially women and girls.

Cutaneous leishmaniasis is a parasitic disease transmitted through the bites of certain species of sand-fly.

It can lead to severe scarring, often on the face, and regularly goes undiagnosed and untreated.

''The number of new reported cases in Kabul dramatically rose from the estimated yearly figure of 17,000 to 65,000 in 2009, mainly among women and children,'' said WHO representative to Afghanistan Peter Graaff.

''This number is likely to be the tip of the iceberg as cases are grossly underreported.''

Several other major cities such as Herat, Kandahar and Mazar-e Sharif are also centres of leishmaniasis.

Social stigma

Leishmaniasis has exploded in crowded neighbourhoods of Afghanistan and spread to hundreds of thousands of people.

''I had the disease - and didn't go to a doctor - but it healed itself after a year,'' said Abdul Ghaffar, 12, in Kabul.

''I am fine now, but I am worried about the scar.''

The Afghan government says the high cost of treatment makes it difficult to hand out drugs for the illness.

The most common form of the disease is not fatal, but still causes misery and social stigma, especially for victims with scarring on their faces and hands.

Those affected develop skin sores which can occur several weeks to many months after the person has been bitten.

Many victims suffer without receiving treatment or a diagnosis

Children are often bullied and women sufferers sometimes find it hard to find husbands.

''Addressing stigma, early diagnosis and early treatment is the only way to go about tackling this disease,'' said Fatima Gilani, director of the Afghan Red Crescent Society.

The disease thrives in post-conflict societies where there is poor sanitation and poor community services. The insects often breed on waste land and in rubbish.

Doctors say that refugees returning from abroad are particularly susceptible as they have no resistance.

Decades of conflict has gravely weakened much of Afghanistan's health infrastructure.

''Our capacity to treat the disease is very low. We can treat only 40% of leishmaniasis cases,'' said Dr Suraya Dalil, acting public health minister.

Over the past few years a handful of foreign troops have also been bitten by the sand-flies and have developed the disease.

Nato camps have been fortified to try to stop the sand-flies and soldiers have been instructed to keep sleeves rolled down and to use mosquito nets and insect repellents.