Pakistan floods: baby victim fights to survive

- Published

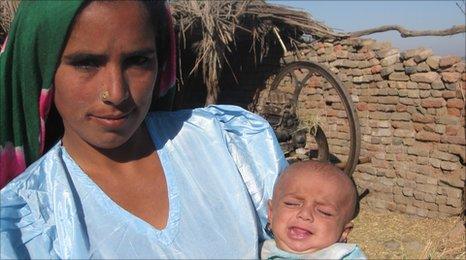

Although Samina is bigger and more robust, she faces a tough winter with the risk of pneumonia

Four months ago, the BBC reported on a baby who was born by the roadside in Sindh Province at the height of the floods in Pakistan. Baby Samina then seemed close to death and her mother struggled to feed her.

Jill McGivering has been back to Sindh to revisit Samina and her family.

It took me a moment to recognise Samina. She is more than three months old now and so much bigger, wriggling and protesting in her mother's arms.

Her mother, Allahrakhi Burro, also looks stronger and clearly delighted to be back in their village.

The family boiled up tea on their open fire and showed me round.

The courtyard was crowded with neighbours and the family's animals - a donkey and its cart and two water buffaloes.

Piles of rubble

The floodwater took weeks to recede.

Now it has gone, the damage to their home is clear. Many of the outside walls have been destroyed.

Most of the rooms have been reduced to a single wall and piles of rubble, all exposed to the sky.

The family pointed out to me where they have started to repair, rebuilding brick walls and coating them with mud and straw.

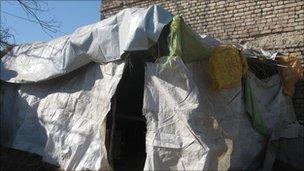

Allahrakhi Burro showed me the corner of the courtyard where she and Samina sleep.

Their low wooden beds are backed up against a wall but the rest of the shelter is makeshift, a mixture of tree branches and plastic sacking.

Not much protection from the cold.

"We don't have enough blankets," she said. "There aren't enough to go round. Just last month Samina was ill."

Samina's father, Gul Khan, is recovering from malaria and still too weak to work.

So the family have no income.

They have been surviving on the rations they were given when they left the relief camp in Sukkur, run by the Pakistani army.

But that food is running low and they often go to bed hungry.

Gul Khan is a mild-mannered man but when I asked him about the government cash compensation scheme and whether he has been able to register for it, he sounded angry.

Part of the family's home is ill-equipped to cope with the ravages of winter

He said that he had tried to register for the scheme, but local officials are demanding bribes of almost $50 (£32) in return for processing claims.

The other men, crowding round to listen, chipped in. Of about 40 families in the village, they said, only four or five had enough money to pay the bribes.

No-one else had been able to register.

"We don't even have enough money to buy food," one man said. "How can we afford to give bribes?"

Everyone here seems relieved to be back in their homes.

Baby Samina looks much bigger and more robust.

But the family's troubles are far from over. Winter is coming. The nights are getting colder and, without adequate shelter, the children face the risk of pneumonia.

They also face financial problems. They need more money to repair their home and they have lost many of their possessions.

They do not have enough money to feed themselves, let alone buy fodder for the animals.

Even when he has recovered from malaria, Samina's father will struggle to find work. It is likely to be a long, difficult winter.