Profile: Muhammad Yunus, 'world's banker to the poor'

- Published

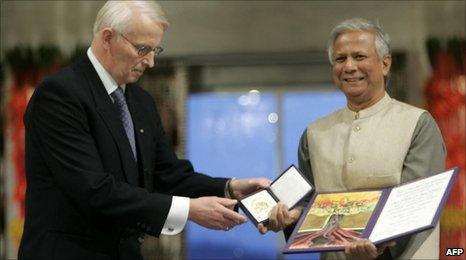

Professor Yunus has earned international recognition for fighting poverty

Muhammad Yunus is often referred to as "the world's banker to the poor". His life's work has been to prove that the poor are credit-worthy and he received the Nobel Prize for Peace in 2006.

His revolutionary microcredit system is estimated to have extended credit to more than seven million of the world's poor, most of them in Bangladesh, one of the poorest nations in the world.

The vast majority of the beneficiaries are women.

Prof Yunus says that he came up with the idea in 1976 while professor of economics at Chittagong University in southern Bangladesh.

The first loans he issued had a value of $27 (£14.50). Their recipients were 42 women from the village of Jobra, near the university.

Until then, the women had relied on local money-lenders who charged high interest rates.

Beggars can borrow

The conventional banking system had been reluctant to give credit to those who were too poor to provide any form of guarantee.

Microcredit has provided a lifeline for the poor in Bangladesh and other countries

The success of Prof Yunus' scheme exceeded all expectations and has been copied in developing countries around the world.

His micro finance initiative reached out to people shunned by conventional banking systems - people so poor they have no collateral to guarantee a loan, should they be unable to repay it.

Prof Yunus has tried to transform the vicious circle of "low-income, low saving and low investment" into a virtuous circle of "low income, injection of credit, investment, more income, more savings, more investment, more income".

It was so successful that even beggars have been able to borrow money under his scheme.

But over the last decade critics say that the microcredit concept - and Grameen's reputation - has lost some of its sheen.

He is battling to remain managing director of the Grameen Bank following an announcement by the government in March 2011 that he had been sacked.

Prof Yunus upset Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina in 2007 by attempting to set up his own political party.

She was under house arrest at the time - the country was being run by a military government - and she saw his move as treacherous.

In December 2010 the prime minister accused Prof Yunus of treating Grameen Bank as his "personal property" and claimed that it was "sucking blood from the poor".

Evidence of the government's desire to take over Grameen Bank became all too clear with its decision to set up a review committee the following month with a remit to look into the bank's affairs.

Around the same time, a TV documentary alleged that aid money had been wrongly transferred from one part of the Grameen group of companies to another in the mid-1990s.

The bank denied all the charges and later the Norwegian government, one of its main donors, gave it the all-clear.

But it was not the first time that Prof Yunus and his Grameen network had attracted negative headlines.

In 2002 an article co-written by Wall Street Journal reporter Daniel Pearl - who was later murdered by militants in Karachi - said that Grameen's performance had not "lived up to the bank's own hype".

It said that in two northern districts of Bangladesh, half the loan portfolio was overdue by at least a year and for the whole bank, 19% of loans were overdue.

The article - parts of which were strongly disputed by Mr Yunus - said that microcredit "had lost its novelty" because so many organisations were competing to provide it.

It also pointed that Grameen Bank - part of the Grameen group of more than 30 companies - was not under any formal supervision.

"They are regulated, but they are regulated by themselves," a director of Bangladesh Bank, the central bank, was quoted as saying.

Correspondents point out that in 2011 the set-up is all the more complicated because some Grameen companies do not operate for profit and some do.

The recent controversies have done little to enhance the overall reputation of the microcredit concept around the world, which recently has come under attack.

Some micro-financial institutions have been criticised over exorbitant interest rates and alleged coercive debt collection.

In the south-eastern Indian state of Andhra Pradesh, for example, micro-loans have been blamed for a series of suicides among struggling farmers.

By 2010 it was estimated that some 250 organisations in the state had handed out loans totalling more than £1.65bn (£883m), but only a small proportion of those were paid back.

Legacy of change

Prof Yunus is renowned for living a simple life and does not seem to let any of this criticism worry him - his supporters point that the Nobel prize is the best answer to his critics.

The Grameen Bank has for some years been majority-owned by the rural poor it serves - apart from the 25% stake held by the Bangladeshi government.

Few dispute that Prof Yunus has created a legacy of real social change in Bangladesh, earning international recognition for his poverty reduction techniques, which have now been embraced by many Western countries.

In 2000, Hillary Clinton famously remarked that Mr Yunus had helped the Clintons introduce microcredit schemes to some of the poorest communities in Arkansas.

"Microcredit is something which is not going to disappear... because this is a need of the people," Mr Yunus told the BBC in 2002.

"Whatever name you give it, you have to have those financial facilities coming to them because it is totally unfair... to deny half the population of the world financial services."

The high reputation enjoyed by Prof Yunus overseas was again made clear in February 2011, when a group of charities led by former Irish President Mary Robinson came to his defence, arguing that he had been unfairly vilified by the government.

The Friends of Grameen group alleged that Prof Yunus had been subjected to "politically orchestrated" and "increasingly aggressive" attacks.

Mrs Robinson said that some highly visible poverty reducing private microcredit experiences had been set up around the world because of the pioneering work of Prof Yunus.

- Published2 December 2010

- Published3 November 2010