Is India star-crossed in Asian space race?

- Published

Moments after take-off last month, India's GSLV rocket ended up in the Bay of Bengal - for the second time in eight months

After gaining in recent years on China in the Asian space race, how seriously have recent high-profile misfires set back India's reach for the stars?

On Christmas Day at India's Cape Canaveral - the Satish Dhawan Space Centre - scientists could only watch in horror as the rocket bearing the nation's hopes for space travel veered off course 47 seconds after lift-off.

Ground control pressed the destruct button and moments later the unmanned Geosynchronous Satellite Launch Vehicle (GSLV) was engulfed by a ball of flame.

Live television pictures showed the rocket exploding in the sky above the Sriharikota launch site, north of Chennai, on India's east coast. The accident cost an estimated $71m.

'Learning curve'

As India's most expensive firework rained into the Bay of Bengal, scientists were left ruing their second consecutive failure to launch the rocket, which had been carrying a communications satellite.

On 15 April last year another GSLV also ended up in the ocean when it malfunctioned 304 seconds after take off.

India's first homegrown cryogenic engine was blamed for that accident.

The Indian Space Research Organisation (Isro) still does not know what went wrong at December's launch, when a Russian-made cryogenic engine was used.

Isro spokesman S Satish said: "As far as the GSLV is concerned, we are still in the learning curve.

"We are confident we will be able to overcome this temporary setback. Isro is an organisation which learns from its failures."

Delhi and Beijing's Moon missions have gained fresh impetus since last year's Nasa budget cuts, which dashed US hopes of a lunar return by 2020 - more than half a century after the Americans' first visit.

India has been playing catch-up on China in the race, a less shrill replay of the one between America and the USSR in the 1960s.

Beijing stole a march in 2003 by becoming only the third nation to fly a man into space - after the US and the old Soviet Union.

In September 2008, a Chinese astronaut, Zhai Zhigang, performed a brief space walk.

India's riposte came two months later.

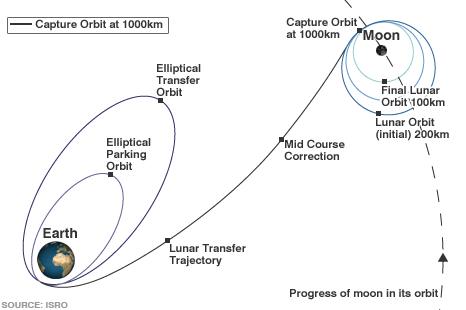

It became the fourth country to plant its colours on the Moon - after America, Russia and Japan - thanks to the success of its Chandrayaan (Sanskrit for "moon craft") probe.

US sanctions lifted

A bullish Isro began talking of a manned lunar mission by 2015. A mission to Mars in 2030 was even mooted.

The space agency has now scaled back its ambitions, and says no date is fixed for a manned Moon trip.

But it still hopes to launch Chandrayaan-2 by 2013, and put a vehicle on the lunar surface.

And it aims to send two Indians into a low space orbit by around 2016.

Dr M Annadurai, director of India's Moon programme, shrugs off last year's setbacks.

"Failures are a part of any space programme," he told the BBC. "We have enough time to think about Chandrayaan-2."

India, which began its space programme in 1963, has already sent an astronaut into space, although that was with the USSR nearly three decades ago.

Washington this week lifted sanctions imposed on Isro following India's nuclear weapons tests in May 1998.

US President Barack Obama had said during his visit to India last November that those measures would be lifted.

Against the clock

India is now firmly back in the game, and Isro insists there will be no more delays to its space programme.

All eyes are now on two satellite launches scheduled to take place in the next three months from Sriharikota.

The GSLV rocket before its ill-fated launch last month

They will be carried by India's other, less powerful, rocket - the Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle - which carried Chandrayaan-1. It has chalked up 16 successful lift-offs.

In contrast, three out of seven GSLV launches have ended in failure, while just one was judged to be partially successful.

India needs the GSLV for its ability to carry bigger communication satellites. To launch its heaviest satellites, the country still relies on European space consortium Arianespace.

The GSLV is integral to the future of India's space programme.

But Dr KR Sridhara Murthi, former head of Antrix Corporation (Isro's commercial arm), feels the clock is against them.

"Isro has to redouble its effort with regard to the GSLV to make up for the lost time. They must also look into alternatives to launch Indian-made satellites," he says.

India is determined to end its dependency on foreign rocket technology, such as Russian engines.

With the next nailbiting GSLV launch expected within a year, experts are working flat out to ensure that this time all goes to plan.

India does not want to end up star-crossed in the Asian space race.

- Published25 January 2011

- Published25 December 2010