Pakistan's evolving sectarian schism

- Published

Sectarian violence has bedevilled Pakistan for much of the last two decades

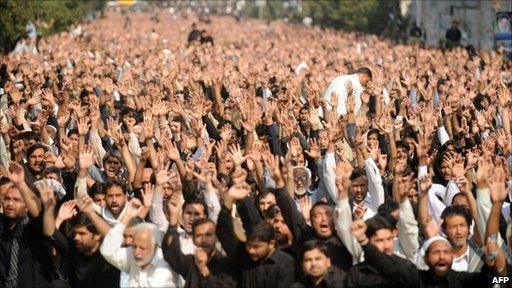

A series of bomb blasts and shootings mostly targeting Pakistan's minority Shia community in recent years shows that sectarian violence in the country can be every bit as deadly as that instigated by al-Qaeda and the Taliban.

Attacks in Karachi, Peshawar, Quetta and the north-west seem to be manifestations of the bitter split between Sunnis and Shias.

In most cases, no-one claims responsibility for such attacks.

Over the past 20 years Sunni and Shia extremists from both groups have attacked each other all over Pakistan.

However analysts say that the bulk of the violence more recently has been committed by Sunni militants inspired by al-Qaeda's ideology.

Their attacks have borne a startling resemblance to bombings carried out by Sunni militants against Shias in Iraq.

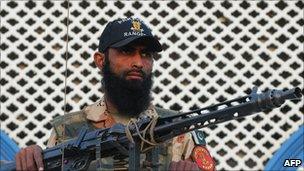

Tough policing

In Pakistan, the focus of the sectarian violence has arguably changed. In the 1980s and 1990s the problem was acute in Karachi and in the province of Sindh.

More visible policing has been used in Karachi to fight sectarian violence

But tough policing - especially in Karachi - towards the end of the 1990s meant that many militants were either killed or arrested.

The BBC's Syed Shoaib Hasan in Islamabad says that sectarian violence has always worsened in Pakistan when the protagonists have a base from which to operate.

That appears especially to be the case in Karachi over the past two years because sectarian violence in the city has made a comeback with police battling to enforce law and order.

A key centre of sectarian violence is the tribal region bordering Afghanistan, where Islamabad is struggling to impose its authority.

The list of recent sectarian attacks makes for grim reading:

September 2011: Gunmen open fire on a bus carry pilgrims at Mastung in Balochistan province. At least 26 Shia Muslims are killed

January 2011: At least 10 people killed after twin blasts targeted Shia Muslim processions in Lahore and Karachi

September 2010: At least 50 people killed in a suicide bombing at a Shia rally in Quetta, south-western Pakistan

July 2010: Sixteen Shias killed in an attack on Shias in north-western tribal areas

February 2010: Two bombs in Karachi kill at least 25 Shias and injure more than 50

December 2009: At least 30 people killed and dozens injured in a suicide bombing on a Shia procession in Karachi

Feb 2009: Bomb attack on a Shia procession in Punjab leaves 35 dead

As the influence of the Taliban grows in the north-west, the fear is that violent sectarian groups will assert themselves once again across the rest of Pakistan - correspondents say recent violence in Punjab province could be a reflection of this.

The group accused of orchestrating the violence in recent years is Lashkar-e-Jhangvi, widely seen as the armed wing of the militant Sunni Sipah-e-Sahaba group.

Previously, Sipah-e-Sahaba itself was accused of the violence, but many analysts argue that Lashkar-e-Jhangvi - inspired both by al-Qaeda and the Taliban - has now broken away from its parent organisation and is responsible for the use of suicide bombers in many sectarian attacks.

In early Islamic history the Shia were a political faction ("Party of Ali") that supported the power of Ali, son-in-law of the Prophet Muhammad and the fourth caliph (temporal and spiritual ruler) of the Muslim community.

Ali was murdered in 661AD and his chief opponent, Muawiya, became caliph. It was Ali's death that led to the great schism between Sunnis and Shias.

Caliph Muawiya was later succeeded by his son Yazid, but Ali's son Hussein refused to accept his legitimacy and fighting between the two resulted.

Hussein and his followers were massacred in battle near Karbala in AD680.

Both Ali and Hussein's death gave rise to the Shia cult of martyrdom and sense of betrayal.

Shia has always been the rigid faith of the poor and oppressed waiting for deliverance. It is seen as a messianic faith which awaits the coming of the "hidden Imam", Allah's messenger who will reverse their fortunes and herald the reign of divine justice.

Today, they make up about 15% of the total worldwide Muslim population.

Zia's legacy

Grave diggers are once again in big demand in Karachi

Thousands of people have been killed in Shia-Sunni violence since the 1980s across Pakistan.

President Asif Ali Zardari is not the only Pakistani leader to have been beset with such problems, which most analysts agree began in 1979 when Gen Zia ul-Haq began "Islamicising" Pakistani politics to legitimise his military rule.

As a result, hardline religious groups were strengthened.

This coincided with a period when parts of Pakistan came to be awash with weaponry as a result of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in late 1979.

US arms and Saudi funds allowed Gen Zia to mount a proxy war in Afghanistan with mujahideen, or holy warriors.

Drawn from Pakistani as well as Afghan and Arab youths mostly educated at religious schools, the mujahideen and their patrons were to become influential actors in Pakistan.

Because Sunnis form a large majority in Pakistan, most of the mujahideen were Sunni too.

Radical Sunni Islamists were able to establish armed groups like Sipah-e-Sahaba.

Shia fighters, too, joined the jihad, or holy war, against Soviet forces in Afghanistan, although their bands were smaller.

They received help from Iran where the Islamic revolution earlier in 1979 had boosted Shia confidence.

The growth of Shia militancy led to the establishment of militant groups such as Tehrik-e-Jafria who have been accused of carrying out tit-for-tat attacks on Sunnis.

After dozens were killed in sectarian attacks, Pakistan's then leader Gen Pervez Musharraf launched a campaign against extremism in January 2002, banning the worst-offending groups.

However, that initiative, along with others launched before it, manifestly failed. Sectarian violence - like militancy in the north-west - seems to be a Pakistani problem that will not go away.