Profile: India's Maoist rebels

- Published

One of the key demands of the rebels is land redistribution

India's bloody Maoist insurgency began in the remote forests of the state of West Bengal in the late 1960s.

Several decades later it had become, in the words of Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, India's "greatest internal security challenge".

Maoists are also known as "Naxalites" because of the violent left-wing uprising in 1967, which began in the West Bengal village of Naxalbari.

Although this was eventually quashed by police, over the years India's Maoists have regrouped and asserted control over vast swathes of land in central and eastern India, establishing a so-called "red corridor".

This spans the states of Jharkand, West Bengal, Orissa, Bihar, Chhattisgarh and Andhra Pradesh and also reaches into Uttar Pradesh, and Karnataka.

The Maoists and affiliated groups are active in more than a third of India's 600-odd districts, the authorities say.

And more than 6,000 people have died in the rebels' long fight for communist rule in these states.

Maoist aims

The Maoists' military leader is Koteshwar Rao, otherwise known as Kishenji.

He reportedly suffered temporary paralysis in June 2010 when a police bullet hit him in the knee.

Normally a regular communicator with the press, Kishenji was little heard of until January 2011 when he issued a statement saying he expected India to succumb to a Maoist revolution by 2025.

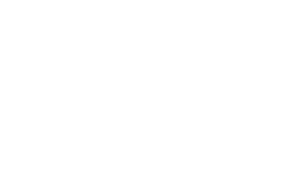

Latest estimates suggest he commandes at least 20,000 armed fighters. They are said to get most of their weapons by raiding police bases.

Analysts say the longevity of the Maoist rebellion is partly due to the local support they receive.

The rebels say they are fighting for the rights of indigenous tribespeople and the rural poor who they say have been neglected by governments for decades.

Maoists claim to represent local concerns over land ownership and equitable distribution of resources.

Ultimately they say they want to establish a "communist society" by overthrowing India's "semi-colonial, semi-feudal" form of rule through armed struggle.

The BBC's Subir Bhaumik in Calcutta says that while there is little prospect of them making any headway in urban areas - or indeed non-jungle rural areas - the rebels remain a force to be reckoned with in remote areas where the security forces are thin on the ground.

Our correspondent says the key question now is whether to deploy the army against the rebels in the same way it has been used in Indian-administered Kashmir and some north-eastern states.

Such a move would be highly controversial, because it would inevitably been seen by some critics as evidence that the rebels are making headway in what is seen by some as "mainland India".

Major rebel attacks

Over the years the Maoists have managed to launch a series of damaging attacks on Indian security forces.

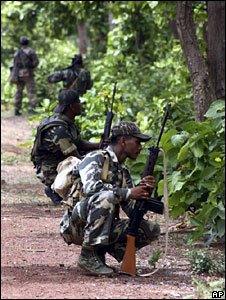

The government has launched several major offensives against the rebels

In 2009, rebels gained virtual control of Lalgarh district in West Bengal barely 250km (155 miles) from the state capital, Calcutta.

For many months, rebels, supported by local villagers, held hundreds of paramilitary forces at bay. The Maoists declared it to be India's first "liberated zone" but Indian security forces finally overwhelmed the rebels.

April 2010 saw rebels ambush paramilitary troops in the dense jungles of central Chhattisgarh state, killing at least 76 soldiers. Correspondents say it was the worst-ever Maoist attack on Indian security forces.

In 2007, also in Chhattisgarh, Maoist rebels killed 55 policemen in an attack on a remote police outpost.

Almost every week, Maoist rebels are blamed for minor skirmishes and incidents across India's north-east - common tactics include blowing up railway tracks and attacking police stations.

In 2010, the Maoists faced India's biggest ever anti-Maoist offensive.

Nearly 50,000 federal paramilitary troops and tens of thousands of policemen took part in the operation across several states.

While the rebels were pushed back deep into their jungle strongholds, they have continued to carry out hit-and-run attacks and numerous high-profile kidnappings.

India's government in turn has pledged to crack down even harder unless rebels renounce violence and enter peace talks.

At the same time there have been differences not just within the central government over how to tackle the rebellion, but also between Delhi and various Indian states affected by the insurgency.

Experts say that disagreements over whether to deploy the army against the rebels is a manifestation of these tensions.

On one issue however the analysts remain united - the chances of any kind of meaningful dialogue with the rebels in the foreseeable future are slim.